WALLACE COLLECTION | MAP | FREE – Check on Free Tours DOWNLOAD MUSEUM MAP

The Wallace is my absolute favorite museum in London. Always quiet, always serene – is perfect antidote to noisy, busy London. The Collection numbers nearly 5,500 objects, a range of fine and decorative arts from the 15th to the 19th centuries. The collection is known for its 18th-century French paintings, Sèvres porcelain and French furniture but also displays other objects, such as arms and armor featuring both European and Oriental objects, as well as displays of gold boxes, miniatures, sculpture and medieval and Renaissance works of art such as maiolica, glass, bronzes and Limoges enamels.

The collection was originally formed from the private art collection amassed by the Marquesses of Hertford, and later expanded by Sir Richard Wallace and his wife. The 4th Marquess literally benefited from ‘fire sales’, the French Revolution and the fire in the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg.

The Dogs, Lobsters & Parrots Tour

Because there is so much to gaze upon, so many details, I have created a fun tour to move you through the museum. A few years ago, I noticed an extraordinary number of parrots and other exotic birds in the Wallace. Parrots were an exotic, expensive symbol globally-expanding trade routes between Europe, and were a way a display wealth and status as a result of slavery, military force and imperialism.

When you enter, go up the beautiful staircase in front of you. The Landing serves as the main orientation point on the first floor. It is hung with mythological and pastoral paintings by Boucher and is also perhaps the best place to admire the wrought iron work of the staircase balustrade, made in 1719 for the Royal bank in Paris.

At the top, on the Landing, look for a cat on a chair.

La marchande des modes (The Modiste)

Studio of François Boucher (1703-1770)

A replica of the picture commissioned in 1745 and delivered in 1746 to Crown Princess Louisa Ulrika of Sweden, now in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm. The subject was originally intended to illustrate Morning in an uncompleted series of the Times of the Day, and is typical of the elegant, contemporary interior scenes painted by Boucher between 1739 and 1746. The Wallace Collection’s picture was probably painted c.1746, before the prime version left the artist’s studio. Although of a good quality, it lacks the vivacity of the original, and was described as ‘after Boucher’ in the sale catalogue of its first owner, Salomon Pierre de Prousteau, in 1769. It served as a model for an engraving by René Gaillard in 1755 (‘La marchande des modes’) and was probably painted specifically as a model for the engraver.

From the Landing, facing the window, turn left into the Small Drawing Room.

Plateau ‘Courteille’ (or plateau ‘de chiffonière’), c1760

Although trays of this model could also be sold individually, they were mostly bought by luxury dealers who had them mounted as the top or shelf of small tables. This piece is decorated with a turquoise-blue ground overlaid with elaborate gilding of trellis-work and cartouches. The painting shows a landscape scene with birds and foxes and probably illustrates an unidentified fable. The contemporary table is by cabinetmaker Roger Vandercruse.

From the Small Drawing Room, take a left into the Large Drawing Room

This room contains some of the most spectacular works by the French furniture-maker, Andre-Charles Boulle.

Still life with a Page, 1644

The dramatic, monumental composition set in a grand architectural interior is typical of Fyt’s work and of mid-seventeenth century Flemish still-life painting in general. A note of extra drama is added to the composition by the blood-stained cloth, the enormous lobster and the contrast of the dead game with the live monkey, dog and parrot. The boy appears to have been added by another artist: an attribution to Erasmus Quellinus has been suggested. The picture was thought to be by Frans Snyders (1579–1657) when purchased with a companion piece, Snyders’s Pantry Scene with a Page (P72).

Red Macaw with other Birds

Willem Hendrik Wilhelmus van Royen (1687-1742)

The picture depicts a red macaw with other birds, including a green parrot, before an extensive river landscape with hunters and anglers. The decorative tonality and subject matter, recalling the pastimes of the elegant elite, are calculated to appeal to aristocratic taste. Richard Wallace bought the painting, with the pendant piece P62, for the 4th Marquess of Hertford at Von Stolberg’s sale in Hanover, they were attributed to Jan Weenix, one of Lord Hertford’s favorite Dutch artists.

White Cockatoo and other Birds

Willem Hendrik Wilhelmus van Royen (1687-1742)

The picture depicts a cockatoo and other ornamental birds in a park setting reminiscent of the still lifes of Jan Weenix (cf. Jan Weenix P59) and of Hondecoeter’s bird pieces (cf. Hondecoeter P64). The decorative tonality and subject matter, recalling the pastimes of the elegant elite, are calculated to appeal to aristocratic taste. Richard Wallace bought the painting, with the pendant piece P67, for the 4th Marquess of Hertford at Von Stolberg’s sale in Hanover, they were attributed to Jan Weenix, one of Lord Hertford’s favorite Dutch artists.

These are birds from the Americas, and were painted when the Dutch empire was expanding its trade in spices, genocide, slavery and sugar.

From the Large Drawing Room, take a left into the Oval Drawing Room.

The Judgment of Paris, 1754

At the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, the goddess Iris threw a golden apple among the guests, inscribed ‘to the fairest’. Venus, Juno, and Minerva all claimed the prize. Jupiter decreed that the shepherd Paris, son of King Priam of Troy, should settle the dispute. When Venus promised Paris the love of the most beautiful woman on earth, he decided in her favor. Boucher skillfully inscribed the scene into an unusual, narrow vertical presenting the three goddesses at different angles and Juno and Minerva in the process of leaving the scene. Boucher carefully prepared the composition with numerous drawings.

But the real question is – why is there a dog in this painting?? 🙂

From the Oval Drawing Room, go straight across into the Study.

Pot à lait ‘à trois pieds’, 1778

The fact that this jug has no cover implies that it was used for cold milk rather than hot, and it was often included with sets of tea wares. Its so-called crabstock handle, gilded to imitate the knotted branch of a crab apple tree, derives from Chinese porcelain. The beautiful scale-pattern was applied by Guillaume Noel (op. 1755-1800) who has outlined each scale in gilding. The birds are probably by Antoine-Joseph Chappuis (op. 1756-1787) who specialized in bird painting.

Les hasards heureux de l’escarpolette (The Swing) 1767-1768

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806)

The painting is Fragonard’s most famous work, and one of the most emblematic images of eighteenth-century art. Compared with the original brief, in the finished painting, the older man is no longer a priest, a barking dog has been added, and Falconet’s sculpture of ‘L’amour menaçant (Menacing Love)’ comments on the story. Fragonard answers the libertine intentions of his patron by picking a Rococo style. Fragonard often employed different styles or languages at the same time, and he seems to have seen a Rococo idiom as particularly apt for an erotic scene. This move has fundamentally shaped perceptions of Rococo art. With Fragonard’s famous work, the style changed its associations. Fragonard combines a backward-looking Rococo element with a pre-Romantic rendering of a forceful and uncontrollable, often obscene nature.

From the Study, go into the little Boudoir Cabinet

There are magnifying glasses at both ends of the room. Portrait miniatures developed out of the techniques of the miniatures in illuminated manuscripts, and were popular among 16th-century elites, mainly in England and France, and spread across the rest of Europe from the middle of the 18th century. Tokens of affection and sentiment, miniatures could be given as gifts to represent love, friendship, or loyalty; Commemorative objects – used to commemorate significant events like marriages, births, or deaths; Private viewing and display – while displayed in cabinets in the museum, they were meant to be viewed up close, revealing the artist’s skill and detail; Personal and Intimate Objects, as an art form for erotic subjects such as mythological tales of the loves of the Gods.

Snuff Box, 1763-1764

Mathieu Coiny (active between: 1723-1788) , Goldsmith

Adrien-Jean Maximilien Vachette (1753-1839), Repaired by, after 1819

An oval varicolored snuffbox enameled “en plein” (enamel applied directly on to the snuffbox) with six reserves depicting a mixture of domestic and urban scenes of everyday life taken from engravings after French painters. The cover and base are bordered with ribbon-tied laurels, scrolls and palms in yellow and green gold. The sides are bordered with scrolls and shells and four pilasters hung with swags. The front rim of the lid appears originally to have opened to reveal a secret compartment, now secured shut with lead solder. The interior of the box is gold. This is a laundry scene. Look for the little dog having a drink.

Snuff Box, 1759-60

The subjects that decorate this box are largely taken from engravings after François Boucher, but translated from the rural exteriors of the originals to rustic interiors. On the lid, the artist has depicted the shepherdess with a sheep, which might, even in the eighteenth century, be considered unusual in a domestic interior. The scene on the front derives from ‘Le sommeil interrompu’ (Interrupted Sleep), although it has been translated indoors and depicted in the opposite sense: this painting by Boucher of 1750 was in the collection of Mme de Pompadour in her chateau of Bellevue.

Snuff Box

Jean-François Breton (1713-c.1791)

This rectangular gold snuffbox has been chased with parallel horizontal lines beneath a pattern of leaves. Decoration in the form of figures, animals and landscape has been enameled in both opaque and translucent colors. On the cover is a scene taken from an engraving by Pierre Aveline of La Vue from a series of the Five Senses published by Nicolas Contat, which shows a shepherdess gazing at her reflection in a stream watched by a shepherd and two figures. The other sides depict similar pastoral scenes; on the base a shepherd asleep by a tree; on the front a shepherdess playing a pipe; on the back a fisherman; on the right-hand side two rabbits and on the left-hand side two exotic birds. The style of decoration, with only the faces in polychrome enamel is very similar to that of Sevrès porcelain in the 1750s.

The Comparison

Attributed to Niclas Lafrensen (1737-1807)

This object does not contain any animals – it is an example of the sort of intimate, erotic miniature that could be enjoyed privately.

From the Boudoir Cabinet, walk into the Boudoir.

Miss Jane Bowles, 1775-6

Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792)

Jane Bowles (1772–1812) was the eldest daughter of Oldfield Bowles (1739–1810), a landowner of North Aston, Oxfordshire, also an amateur painter and musician. Allegedly, Bowles was concerned about Reynolds’s experimental use of materials but was advised by Sir George Beaumont that ‘even a faded picture from Reynolds will be the finest thing you have.’ Reynolds was then invited to dinner with the Bowles family and played games with her to win her confidence. Records of payment indicate that the portrait was painted between 1775 and 1776, when the sitter was three or four years old. Miss Bowles is portrayed in a fanciful theatrical costume, kneeling and embracing her pet spaniel. The lively and spontaneous composition recalls Reynolds’s ‘fancy pictures.’ The beam of sunlight, which shines through the foliage on the right hand side of the picture, is boldly painted in a few decisive strokes of paint.

From the Boudoir, turn into the West Room.

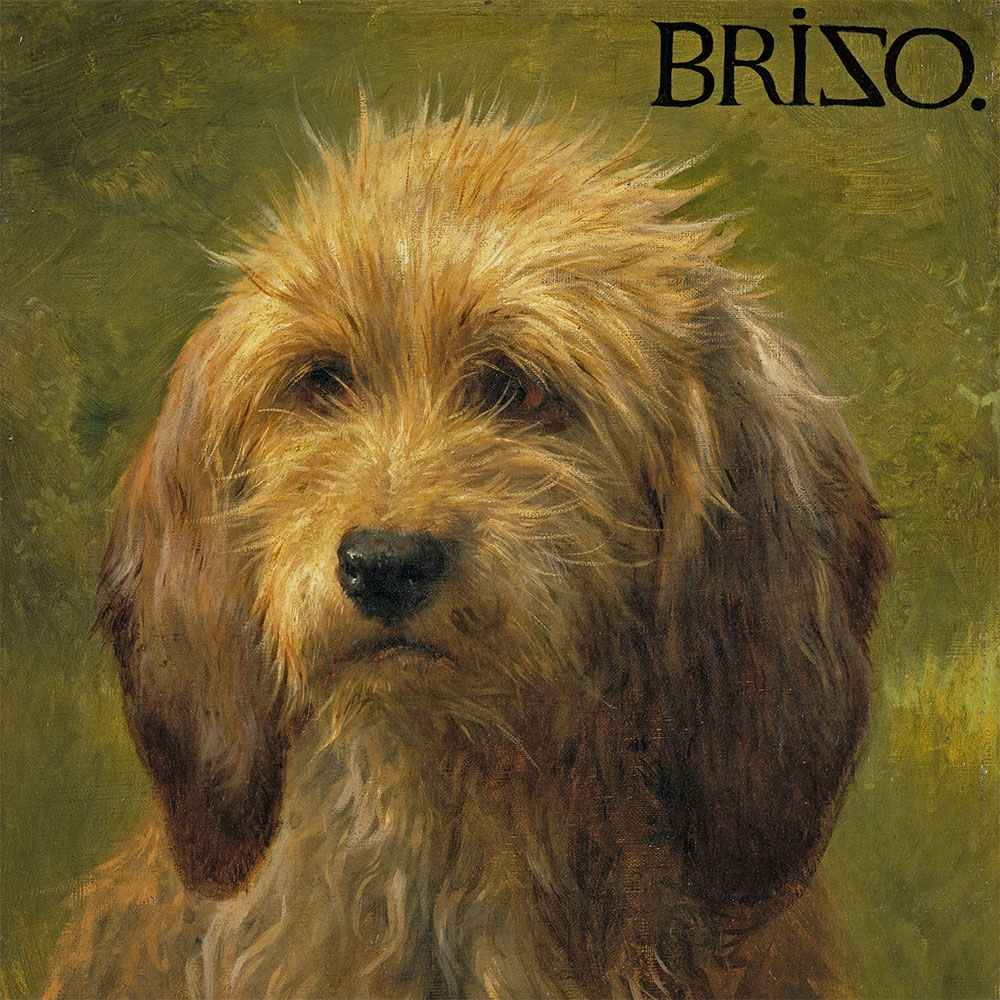

Brizo, A Shepherd’s Dog, 1864

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899)

I LOVE this guy. And I love Rosa Bonheur. Make sure you see her masterpiece someday at the Met, The Horse Fair.

The dog is a female otterhound. Otterhounds were usually kept in packs and the breed is an unusual choice for a shepherd’s dog, although the Kennel Club describes otterhounds as ‘aimiable and even-tempered’. The reference to a shepherd’s dog in the title dates from the first catalogue of the Wallace Collection’s paintings, published in 1900, rather than earlier inventories. The inscription has probably been added by a later hand. Brizo was an ancient Greek goddess, the protector of sailors and fishermen.

Doubtful Crumbs, 1858-9

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899)

This painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy of 1859. A black and tan terrier looks longingly at a bone guarded by a dozing St Bernard. Landseer’s ability to humanize his animals was one of the principal causes of his success with collectors and the Victorian public. The humorous juxtaposition of two dogs of very different sizes was the subject of several of his pictures, notably ‘Dignity and Impudence’ (by 1839, London, Tate).

Mrs Mary Robinson (Perdita), 1781

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788)

Mary Robinson (1758–1800) was one of the best known actresses and writers of the 18th century. She was also one of the most painted and caricatured woman of the period. Having first appeared on stage in 1776, it was a later performance in The Winter’s Tale for which the actress became particularly famous; a part which earned her the nickname ‘Perdita’. It was in this role that Mrs Robinson first caught the attention of the Prince of Wales (later George IV), with whom she went on to have a brief but notorious affair.

This portrait was commissioned in 1781 by the Prince of Wales (later George IV). He had ended a brief affair with Mrs Robinson, who then sought financial compensation from him; after Robinson resorted to blackmail, he eventually agreed to a settlement in August of that year. Mrs Robinson is depicted holding a miniature portrait of the Prince (1735–1789), a gift from him during their liaison.

Miss Nelly O’Brien, c. 1762–64

Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792)

Nelly O’Brien (d. 1768) was a well-known beauty and courtesan, who sat for Reynolds on a number of occasions between 1760 and 1767. O’Brien is portrayed in fashionable contemporary dress, holding a Maltese lapdog. By c.1763, she was the mistress of Frederick St John, 2nd Viscount Bolingbroke (1732–1787). However, there is no evidence to suggest that the portrait was commissioned. Rather, it is thought that Reynolds painted it without a particular buyer in mind, as a means of demonstrating his skills. The portrait is notable for its interplay of light and shadow, particularly in the upper part of the sitter’s body, where the wide brim of the bonnet casts a shadow over her face and bosom. Reynolds rendered with great subtlety the different tones, colors and fabrics of eighteenth-century costume, particularly in the skirt area, where a transparent layer of lace is convincingly and effectively portrayed overlying the quilted material underneath.

From the West Room, walk into West Gallery I

Venice: the Molo with Santa Maria della Salute, c.1740-5

Canaletto (1697 – 1768)

This view, framed by the Doge’s Palace on the right, looks across the Piazzetta, past the columns of San Todaro and the library, towards the mouth of the Grand Canal with the church of Santa Maria della Salute and the Dogana (or Customs House) on the opposite bank. The Giudecca with the church of the Redentore are just visible on the left. Together with its pendant (P509), this view was very popular with Canaletto’s patrons and was engraved in 1742 by Visentini for wider dissemination. At least five other sets are known.

Lots of little dogs to ferret out in most of Canaletto’s works.

Venice: the Riva degli Schiavoni, c.1740-5

Canaletto (1697 – 1768)

The promenade or Riva degli Schiavoni depicts a view still familiar today, with its gondolas bobbing on the water before the Doge’s Palace, one of the best-known buildings in Venice, on the left. The columns of San Todaro and of the Lion of Saint Mark stand on the Piazzetta in front of the Palace, with the Ponte della Paglia and the Prison beyond. This view, along with its pendant (P516), were very popular with Canaletto’s patrons: they were engraved in 1742 by Visentini, and at least five other sets are known.

Lots of little dogs to ferret out in most of Canaletto’s works.

From West Gallery I, walk into West Gallery II

Edward V and the Duke of York in the Tower, c.1740-5

Hippolyte (Paul) Delaroche (1797 – 1856)

This is a replica, painted for engraving, of a much larger picture (Paris, Louvre) exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1831. The subject is probably taken from Shakespeare’s ‘Richard III’, IV, iii. Edward V (1470-83) succeeded to the throne on the death of his father Edward IV. He was deposed by his uncle, the Duke of Gloucester (who became Richard III) on 22 June 1483. Shortly afterwards, he and his younger brother, Richard, Duke of York (1472-83), were murdered in the Tower of London. In Shakespeare’s play the murder of the brothers is related by Sir James Tyrrel, Richard III’s henchman, rather than shown on stage. Fittingly, this painting, with its stage-like setting and melodramatic subject, is highly theatrical. The dog and perhaps the young Duke of York sense the arrival of the approaching murderers. An ominous shadow can be seen at the bottom of the door to the bedchamber. The presence in the composition of the bed, the prie-dieu and the missal which the brothers have been reading indicates that Delaroche is making a subversive reference to the traditional subject of the Annunciation (cf. Philippe de Champaigne, ‘The Annunciation’, P134). the illumination on the left-hand page of the missal represents the Annunciation. This is one of several paintings by Delaroche where he grafted some of the classic structures of the great European tradition on to his compositions – a technique used earlier by David and Gros and also by, among others, Gericault and Bonington among Delaroche’s contemporaries.

From West Gallery II, walk into West Gallery III

LOTS of dogs, camels and horses in this room…

Francesca da Rimini, 1835

Ary Scheffer (1795 – 1858)

There are no animals in this painting – I just love the subject. Scheffer enjoyed enormous success with sentimental and religious scenes, many of which became the subject of popular engravings. ‘Francesca da Rimini’ was one of his most admired works – this is the first version. George Eliot said of a version that was exhibited in England in 1854 that she ‘could look at it for hours’. A subject from Dante’s ‘Inferno’, the painting shows Dante and his guide, the Roman poet Virgil, during their passage through Hell. They look on the tragic figures of Paolo and Francesca, condemned with the souls of the lustful to the stormy darkness of Hell’s second circle. Francesca was forced to marry the hideous Gianciotto da Rimini, but fell in love with his handsome younger brother, Paolo. In 1285 they were murdered by Gianciotto after he saw Paolo kiss Francesca while they were reading an account of the love of Sir Lancelot for Queen Guinevere.

The Dog of the Regiment Wounded, 1819

Horace Vernet (1789 – 1863)

See also this painting’s pendant, ‘The Wounded Trumpeter’, P613. These pictures were among Vernet’s most popular works – the critic Sainte-Beuve later remembered engravings of them ‘in every shop window’. In ‘The Dog of the Regiment Wounded’ the two soldiers from the period of the Empire who attend the wounded dog appear to be a bugler of the voltigeurs (light infantrymen) and a drummer of the grenadiers de la ligne (though musicians were permitted considerable licence in their choice of uniform). In the companion picture animals show concern for a soldier, here soldiers show concern for an animal. Both paintings were exhibited, without their titles, at the Paris Salon of 1819. One critic, Étienne Jouy, noted wryly that, whereas he heard many visitors exclaim ‘oh the poor dog!’ he never heard one say ‘oh, the poor trumpeter!’

From West Gallery III, walk into the Great Gallery

A Cockerel with other Birds, 1668-95

Melchior d’Hondecoeter (1636 – 1695)

Melchior d’Hondecoeter was born into a family of artists in Utrecht and studied with his uncle, Jan Baptist Weenix. He specialized in bird subjects, his early work being much influenced by his cousin, the still life painter Jan Weenix. It is difficult to date his paintings as there is very little discernible development in style from his earliest dated works of 1668. In this painting, a peahen, peacock, hen and cockerel are in the centre of the composition, with a waxwing and bullfinch above and shellducks and swans to the right. It was bought by the 4th Marquess of Hertford before 1854, when it was seen at Hertford House by the art historian Gustav Waagen.

Still Life with Parrot, c1645-60

Pieter de Ring (1615 – 1660)

Pieter de Ring was a pupil of Jan Davidz. de Heem, whose style he closely imitated, specializing in elaborate banquet pieces or pronkstilleven. His known works date from 1647 onwards and he joined the Leiden Guild in 1648. The cluttered composition of this painting is typical of De Ring’s work. The various elements of the still life may carry symbolic meanings; thus the laurel wreath round the glass on the left may imply praise of wine, and the partly cut melon may indicate moderation. The picture is signed with Pieter de Ring’s rebus, a ring.

Still Life with Lobster, 1643

Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606 – 1684)

De Heem was best known for his still life depictions of the banquet table, of which this is a fine example. It is a virtuoso display of his ability to capture a variety of material textures in paint, from the mouth-watering display of fruit to the skillfully painted reflective surfaces of pewter plates, a drinking glass and silver flagon. De Heem places the still-life elements before a dark wall and then focuses light upon them from the top left. The stark contrasts of light and shade intensify the dramatic effect and lend the picture a peculiar mood of intimacy. On careful inspection, the image is not as straightforward as it first appears: the image of the artist at work can be seen reflected in the shiny surfaces of the drinking glass and flagon. Moreover, the position of the glass, poised precariously on the jewel box, may suggest the insecurity and fragility of life itself, thus prompting the viewer to look beyond the material display to the spiritual world beyond. It was acquired by the 4th Marquess of Hertford in 1843.

Landscape with Apollo and Mercury, 1660

Claude (1604 – 1682)

Claude was born in the Duchy of Lorraine (in present-day France) but spent his career as a landscape painter in Rome. His originality lay in his masterly depiction of light, which both unifies his compositions and enhances their poetic mood. In this painting Claude depicts the luminous morning light of the countryside around Rome (the Campagna), which he drew and painted throughout his career.

The figures are drawn from the Latin poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses: the Roman god Apollo in the foreground plays the pipes in memory of his lost love, Coronis. In the background, Mercury takes advantage of Apollo’s distracted state of mind to steal his cattle. Technical analysis has revealed that Claude’s original composition did not include the dog and that Apollo was depicted seated in a different position. These additions and changes were made to the painting at a later stage, probably by the seventeenth-century Flemish painter Cornelis de Wael, the first owner of the painting.

From the Great Gallery, walk into East Gallery III

Almost every painting in this room has a dog, cow, goat, horse or chicken…

Dogs in Dutch Genre Painting

Dutch 17th century art is full of dogs. The highly popular (then and now) and numerous genre paintings feature our furry friends so often, they seem part of the furniture. Not only were dogs useful, loved and popular companions, they also made fabulous painting models. Spaniels especially feature repeatedly in these beautiful little art works.

Genre painting is a term which the Dutch did not use in the 17th century. The term was invented in the 19th century to refer to paintings depicting every day life. The works of Dutch 17th century masters such as Johannes Vermeer, Metsu, Jan Steen and De Hoogh have made the topic forever popular, depicting such timeless characters, morals and topics we still identify with today.

Dutch genre paintings was probably even more popular in the 17th century itself, decorating the beautiful homes of the many rich traders who made Holland flourish. Genre paintings often show cafés and brothels but also quiet interiors with women doing a domestic job, writing a letter or looking in the mirror. The genre painters of the time all lived and worked, although in different cities, close together and they knew each other and each other’s work. Topics, compositions and model poses were copied and borrowed, improved upon and given a new twist.

n the more quiet interior scenes we often see little (sometimes tiny) spaniels that are clearly companion dogs to the lady in the picture. Many Dutch 17th century genre paintings are full of moralistic symbolism and the dogs in these pictures are part of that scheme. When they warn us of loose morals in brothel scenes, they remind us of (marital) loyalty in quiet domestic scenes. And like dogs, children can be trained into good and well behaved adults through education and schooling.

The Lute Player, 1711

Willem van Mieris (1662 – 1747)

The bas-relief in the left background of a man embracing a woman, and the naked statues of Venus and Hercules, provide an erotic mythological subtext to a scene of contemporary seduction, where a gentleman offers a lady a glass of wine. His intentions are made clear by the large plate of oysters – a well-known aphrodisiac – in the foreground. The lady, however, seems hesitant. Musical accompaniment often symbolizes amorous harmony, but here the lady holds, rather than plays, her theorbo. Two figures look on, intrigued by the proceedings.

From East Gallery III, walk into East Gallery II

Interior of the Oude Kerk, Delft, 1651

Emanuel de Witte (1617 – 1691)

I absolutely love netherlandish church interiors. The walls an ceiling are so sepulchral, dignified, spiritual, but the church floor frequently has markets, commerce, trade – all manner of things going on – and there’s always a dog. At the time, in inclement weather, the church may have been the only large building to conduct business in. De Witte demonstrated a sophisticated response to the difficulties of representing monumental interiors. Not content to record detail and perspective, he aimed to suggest space and atmosphere through evocative contrasts of light and shadow, in much the same way as his contemporaries in Delft, Vermeer and De Hooch. The bare white interior of this church and the central position of the large pulpit reflects the Protestant doctrine of the primacy of the word (the sermon). The bright rays of sunlight relieve the powerful weight of the columns and help to create an illusion of space. The people in the church are also emphasized in this way, as light catches their clothing and provides vivid accents of color.

From East Gallery II, walk into East Gallery I

The Listening Housewife (The Eavesdropper), 1656

Nicolas Maes (1634-1693)

One of Maes’ most original genre motifs was the interior with an eavesdropper, here an elegant housewife, who smiles engagingly, inviting the viewer to witness the misbehavior of the servants downstairs. Maes employed a device known in Dutch as ‘doorkijkje’, literally looking through a door, which opens the vista from one room to another offering a glimpse of action beyond the main scene. This device had been used in northern art as early as the fifteenth century. The painting’s warm palette and strong light and shade effects relate it to Rembrandt, but Maes’ originality lies in the emphasis on the illusion of interior space. The light here not only serves the depiction of space and depth, but also underlines the judgmental attitude, by contrasting the calm and probity of the dining room with the moral as well as physical descent towards the heated kitchen. Look for the kitten.

From East Gallery I, walk into East Drawing Room

Jochem van Aras with his Wife and Daughter, 1654

Bartolomeus van der Helst (1613 – 1670)

In this lively family portrait, signed and dated 1654, Bartholomeus van der Helst painted Jochem van Aras, a well-to-do baker and merchant from Amsterdam, with his wife Elisabeth Claes Loenen and their only surviving daughter, Maria van Aras. The painting celebrates the family’s wealth in their fine clothes, while a glimpse of what is probably their country estate (near Haarlem) is visible in the landscape on the right.

The hare the woman proudly displays not only celebrates her husband’s hunting prowess, but is a reference to the extension of the right to hunt, until recently the exclusive privilege of the aristocracy, to the wealthy middle classes.

Go back down the stairs and at the bottom, turn left into the Front State Room

Lady Cockburn and her three eldest sons, after Reynolds, 1842

Henry Pierce Bone (1779 – 1855)

Lady Cockburn had six children and three stepchildren. Remarkably, her sons in this portrait became a Major-General, an Admiral and the Dean of York. Reynolds’s composition recalls earlier allegorical representations of Charity, particularly two paintings by Van Dyck, one of which is now in the National Gallery.

From the Front State Room, turn into the Back State Room

Armchair, 1780-1855

Georges Jacob (1739–1814)

This armchair is one of a set of six chairs and two sofas. The chairs were made by the workshop of Jacob, which produced a wide range of furniture in the neo-classical style. The Beauvais tapestries now on all the pieces are not the original covers and date from twenty years earlier than the armchair frames, to which they were probably applied in c.1850. Their designs are by Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755) who, in addition to being the leading animal painter of his time, was director of the Beauvais manufactory. The back of this chair shows a dog raising a pheasant and the seat shows a parrot and perhaps a guinea pig. The two sofas were made to match the chairs in the nineteenth century, probably in order to display the large Oudry tapestries.