BRITISH MUSEUM | MAP | FREE – Check on Free Tours DOWNLOAD MAP

Open: Daily: 10am – 5pm, Friday: 10am – 8:30pm

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human culture from its beginnings to the present. Established in 1753, the British Museum was the first public national museum. In 2023, the museum received 5,820,860 visitors, 42% more than the previous year. So if you go – go early!

The museum has a wide variety of places to eat, from little cafes and a pizzeria to a fancy restaurant.

PLUNDER & LOOT TOUR

The subject of repatriation is extremely complex and nuanced. At the very least we should always apply the dialectic to any discussion – and a big dose of compassion too.

There are five major methods by which non-Western works of art made their way into Western museums or other public sites of display: military plunder, diplomatic gifts, antiquities dealers, stationary excavations and mobile expeditions. Of these, military plunder is the least likely method of acquisition and antiquities dealers are the most. Military plunder is easy to criticize. But it was not the norm. Museums do not maintain, nor have they ever maintained, standing armies. Their institutional strengths are to be found in their purses, which are filled by wealthy donors and government coffers.

The British Museums stirred up a popular storm when it was first released, with even late-night talk show host John Oliver taking up the cause of restitution for the Benin Bronzes, calling their removal an act of ‘cultural genocide’ in front of a live studio audience. ‘For that kingdom, these were their memories made physical,’ Oliver shouted at his audience.

‘And these plaques were laid out in a very specific order, which was then lost when the British tore them from the palace walls, meaning the British, in effect, stole and scrambled a nation’s memories, a crime so fucked up even [the science-fiction/ horror show] Black Mirror hasn’t thought of it yet.’

Museums: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver

Oliver then superimposed an image of the cover of Hicks’s book on the television screen to lend academic gravitas to his vulgar monologue. Here at last the discourse of criminalization had reached its hyperbolic apogee: from ‘plunder’ and ‘rape’ to a crime so ‘fucked up’ that it constituted ‘cultural genocide’.

There are several glaring omissions of historical context in such arguments.

First and foremost is the fact that exquisitely manufactured objects such as the Benin Bronzes were not made for the masses, the people. They were commissioned by wealthy elites to serve as exclusive emblems of political power and social status. This lent substance to the monarch’s jealously guarded right to rule over his or her subjects, whose labour and taxes would be funneled into grand palaces and lavish works of art that the masses themselves would never get to see or enjoy.

The Benin Bronzes, much like the extravagant collection of Chinese bronzes, porcelains and paintings stored in the Forbidden City, were not originally regarded as symbols of any nation, nor did they tell that nation’s ‘story’.

If they told any story at all, it was one that extolled the character, taste and rule of the haughty kings and emperors who jealously hoarded them – and of the gods who supposedly blessed them.

There is an bigger problem with the criminalizing discourse of modern cultural polemics, one that goes far beyond the mere lack of historical context or nuance. And that problem is this:

Regardless of whether the Benin Bronzes represented the inclusive memories of the Nigerian nation or were vain, self-congratulatory indulgences of the Benin elites, the method of their removal from Africa to Europe was merely one out of many.

And this particular method – military plunder – was highly irregular and decidedly unrepresentative of how most artifacts and artwork from the non-Western world found their way into Western museums. Military plunder involved hundreds or thousands of armed men, acting on orders from their superiors, shooting their way across the land in an attempt to break into a palace or fortress with the explicit intent to maim and kill anyone who got in their way. If the soldiers happened to survive all this carnage, blood-stained loot was one of their rewards.

Military plunder is easy to criticize. But it was not the norm.

Museums do not maintain, nor have they ever maintained, standing armies.

Their institutional strengths are to be found in their purses, which are filled by wealthy donors and government coffers.

The foot soldiers who actually carried out plunder in distant lands – poorly educated young men drawn from less privileged sectors of society – were rarely inclined to donate their hard-fought spoils of war to any institution without financial compensation.

So in most cases, whenever a Western museum acquired objects looted by Western armies, it did so not by ordering its ‘armies’ to hand them over, but by writing a cheque – if not to the soldier who physically looted them, then to the wealthier collector, dealer or auction house who first bought them from him.

To skeptical readers, this may seem like a small and meaningless distinction. So what if museums merely paid someone else to acquire their morally tainted goods? Doesn’t that make them the institutional equivalent of a person who hires a hitman to carry out a murder? With specific regard to military plunder, the answer is yes – they are indeed morally equivalent.

But once we acknowledge the obvious yet overlooked fact that museums themselves did not send armies overseas, it forces us to pay closer attention to the sorts of vendors from whom museums purchased their collections.

The curators who worked in Western museums did not personally transport the objects under their care. It is more accurate to say that they purchased them.

And soldiers and generals were merely one of several different types of suppliers to whom they made payment.

To put this particular supplier – the soldier – into perspective, consider the fact that the British Museum contains around 8 million objects in its collection.

Of those 8 million objects, just under two hundred consist of bronze plaques taken by British soldiers during their bombardment of the Benin Kingdom in 1897.3 This comes out at 0.000024 per cent of the total collection.

So where did the lion’s share of any given museum collection come from?

Who else, besides gun-toting infantrymen, got a fat cheque for their exquisite wares?

A few examples may help to place the Benin Bronzes into proper relief.

MOBILE EXPEDITIONS – The Lost Manuscripts of Dunhuang

When the Hungarian-born British archaeologist Aurel Stein organized an expedition to the northwestern desert regions of the Qing Empire in 1906, he succeeded in gaining access to a hidden ‘cave library’ (although it was more a storage room than an actual library) near the oasis of Dunhuang. Sealed at some point during the early eleventh century and then forgotten about for the next nine hundred years, this hidden alcove – now known as Cave 17 – yielded more than 40,000 ancient manuscripts and paintings. Stein managed to bring fewer than 10,000 of them back with him to England. And this was the spoils from merely a single site on one of Stein’s many expeditions. Many other Western scholars also brought back thousands of scrolls from Cave 17, including the French sinologist Paul Pelliot, who matched Stein’s total just one year later. And when Stein returned to the abandoned oases of the Taklamakan Desert again in 1913 to collect even more ancient Buddhist antiquities, his total haul was so large it had to be expressed in weight rather than objects: 7,250 kilograms – that is, 16,000 pounds! That’s more than 7 tonnes of so-called ‘loot’, and none of it heavy bronze plaques. But even ‘heavy loot’ must contend with the ultimate gold standard: when Lord Elgin brought his marbles from Greece to London and put them on display in 1807, they tipped the scales at a whopping 109 tonnes (240,300 lb).

Neither Stein nor Elgin acquired these future museum objects in a manner that could be described as military plunder. Though Stein did carry firearms, they were intended to guard against possible bandits in remote desert regions. As it turned out, Stein used them only to hunt game.

DIPLOMATIC GIFTS: Elgin Marbles

Lord Elgin, for his part, was unarmed, as any gentleman diplomat should be. Not only this, but he was in fact the flesh-and-blood embodiment of Great Britain’s military alliance with the Ottoman sultan against the French Navy in the Mediterranean. As British ambassador to the Sublime Porte in Constantinople, Elgin was the political liaison through which Ottoman gratitude for the recapture of their Egyptian province from Napoleon would be expressed. And that gratitude came in the form of permission – both written and oral – to remove ancient Greek sculptures from the Parthenon in Athens.

STATIONARY EXCAVATIONS: Tutankhamun’s Tomb

Consider, for instance, the much celebrated tomb of the boy pharaoh Tutankhamun, discovered by the British archaeologist Howard Carter in November 1922 in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt.

By the time Carter finished his survey of its densely packed treasures, the catalogue included more than 4,000 objects. Though nearly all of them ended up in the National Museum in Cairo rather than in the British Museum in London or the Metropolitan Museum in New York – as Carter’s wealthy patron, Lord Carnarvon, originally planned – their sheer number still gives us a sense of just how many museum artifacts could be found in countless ancient tombs across the globe, even if they had not escaped (as had Tut’s tomb) the covetous covetous hands of ancient tomb robbers. Regardless, royal tombs like those found in the Valley of the Kings tended to be located far from major population centers – and thus quite remote from the intended victims of marauding armies. Not surprisingly then, Carter’s work in the Valley of the Kings, and that of every foreign archaeologist before him, highlights yet another category of acquisition: stationary excavations.

DEALERS

Last but not least are the dealers.

While museums may be willing to write cheques to soldiers, diplomats and scholars, such vendors are relatively few in number (even if the collections of the latter two may occasionally be disproportionately large).

Far more ubiquitous are the networks of antiquities dealers.

Easily the least studied and most poorly understood of all potential vendors that museums dealt with, dealers were almost certainly responsible for the vast majority of objects that you can see in most major museums around the world today. This is due to the fact that they were easy to do business with and as numerous as flies.

By contrast, the spoils of military plunder and diplomatic gifts appeared only intermittently and without much warning – curators could not anticipate when such objects would become available for purchase, nor could they craft their annual budgets and exhibitions around their unexpected arrival.

The mobile expeditions and stationary excavations of scholars were likewise filled with uncertainty.

By contrast, dealers were businessmen. And the success of their business depended primarily on securing a reliable supply of goods to sell to museums on the basis of mutually recognized valuations established by past precedent.

Not only that, but dealers could also fulfill commissions for specific objects ‘on demand’, so to speak, in order to fill in the gaps of a particular collection. In other words, dealers were predictable, reliable and pliable – three traits that made them irresistible vendors for museums.

As a result, according to Egyptologists Fredrik Hagen and Kim Ryholt, ‘most Egyptian objects in Western museums have been purchased rather than excavated.’

Stationary excavations, mobile expeditions and military plunder get all the attention because they make for compelling, easily comprehensible stories. The agents of good and evil are always easy to identify.

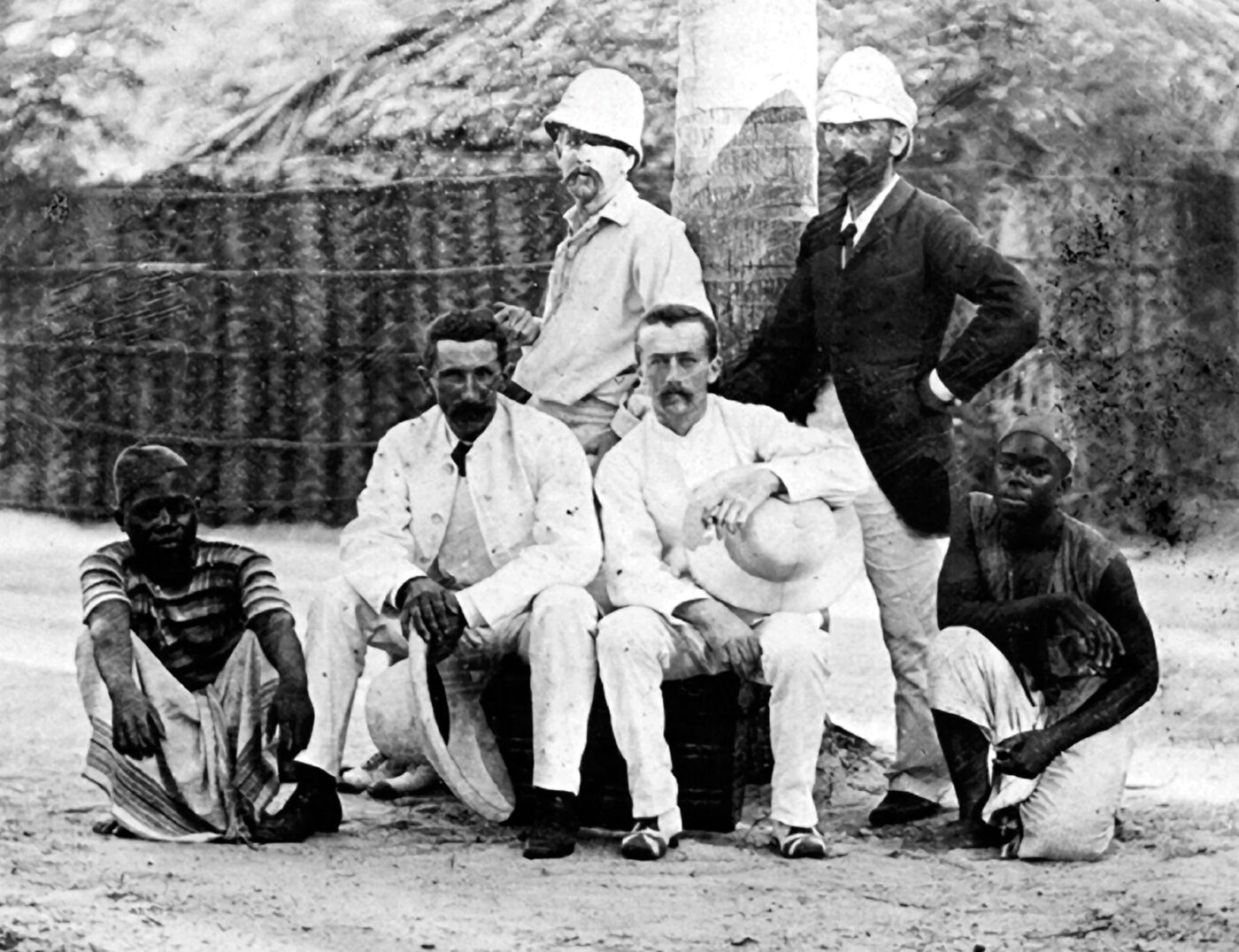

The former narrative involved brave soldiers defending their nation’s honor, sailing to far-off lands to teach indulgent Chinese mandarins a lesson and punish dark-skinned savages in the African jungle for their treachery.

We now hear tell of smug white soldiers who brutalized oppressed colonial peoples in bloody pursuit of imperial loot and of racist scholars who manipulated the supposedly altruistic discourse of science as a perverted cover for their imperialist schemes of native disenfranchisement.

This new set of stories is just as simplistic and dismissive of historical nuance as the self-serving narratives they aim to replace.

Worst of all, they make virtually no allowance for the recognition of crucial distinctions among different means of artefact acquisition: as the discourse surrounding the Benin Bronzes clearly shows, everything in a museum is now regarded as stolen and equated with cultural rape and genocide.

Soldiers, dealers, diplomats or scholars – what difference does it make? They were all imperialist thieves regardless.

THE PAST

We approach the past with preconceived notions modeled on our own unique experiences, only to find that the equally unique conditions of a different day and age produced behaviors of a different sort that are hard to comprehend today. If this is the case with our own ancestors, how much more so with people who lived centuries ago in lands halfway across the globe?

And yet most of us have little compunction in speaking on behalf of long-dead Egyptians, Persians and Chinese people. We imagine, with little to no historical evidence, that they must have shared the same sort of views that we hold today.