The Gweagal Shield

THE GWEAGAL SHIELD

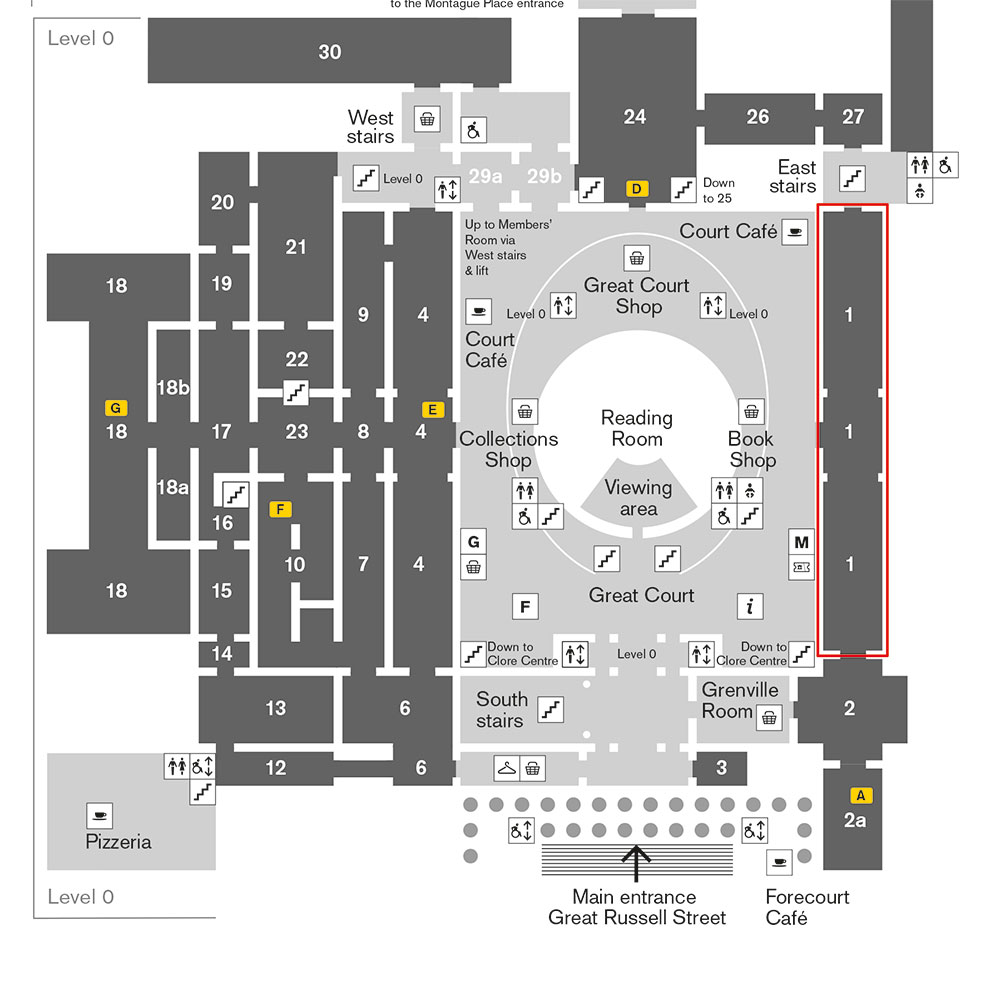

When Lieutenant James Cook landed, uninvited, onto the continent now known as Australia, he began a colossal theft. The British colonial project initiated by his landing not only involved the mass theft of Aboriginal land, but also of sacred Aboriginal objects made from it. Still today, many of these objects sit inside glass cabinets in museums around Europe. For at least the past 50 years, the British Museum has claimed to have had in its possession an Aboriginal bark shield used to defend against Cook’s first landing in 1770 onto the continent now known as Australia. The shield is on permanent display in the museum’s ‘Enlightenment Room’, and was chosen to feature as part of the museum’s 2010 BBC collaboration, A History of the World in 100 Objects, and its 2015 Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilization exhibition.

As an Aboriginal defensive weapon used in the highly consequential moment of first British contact, the shield is of obvious significance to Aboriginal, Australian, and British colonial history.

But in a shocking revelation explained in two articles in the most recent volume ofAustralian Historical Studies (‘A Case of Identity: The Artefacts of the 1770 Kamay (Botany Bay) Encounter’ by Nicholas Thomas, and ‘A Shield Loaded with History: Encounters, Objects and Exhibitions’ by Maria Nugent and Gaye Sculthorpe), the British Museum and academics working with the institution are now claiming that the shield is not that from Cook’s landing after all.

Indigenous peoples argue that the methodologies used to make these claims are all located within a Western epistemological framework, and that the use of Indigenous and anti-colonial methodologies would have yielded different conclusions.

Gweagal Spears Returned

Why the British Museum MUST return Australia’s Aboriginal Artefacts

Indigenous Australian campaigner tells British Museum to return stolen shield

Until very recently, the narrative that the British Museum has consistently given about the shield in question is that it is, or is at least very likely to be, the one referred to in the Endeavour journals of both Cook and English botanist Joseph Banks.

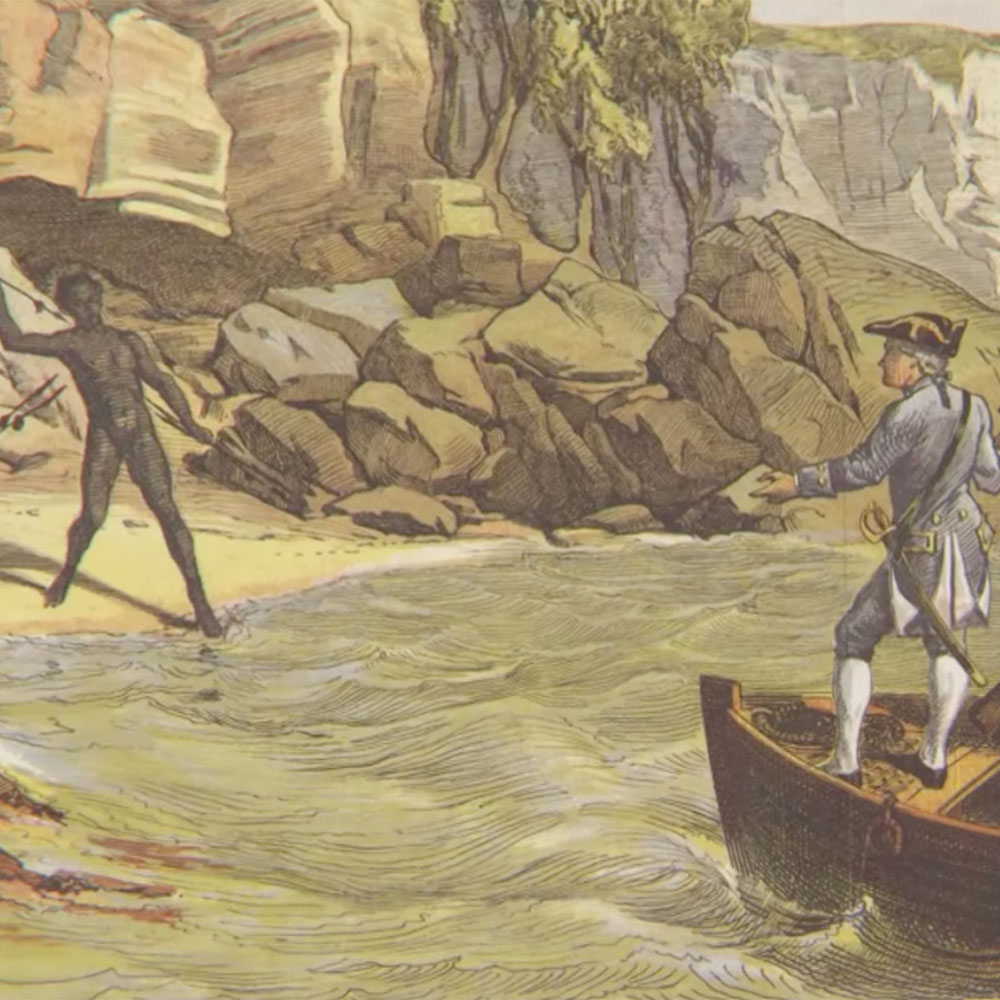

In their journals, both Cook and Banks refer to a shield used by one of the two Gweagal men who Cook fired at as he made his uninvited landing on that fateful day in April 1770. The shield was then dropped on the beach, where Cook collected it. Together with other Aboriginal objects taken by Cook and Banks, the shield was then brought back to England, where it has been treated as a colonial trophy and Indigenous specimen ever since.

This narrative was the key reason Rodney Kelly, a Gweagal man living in Bermagui, travelled to Canberra in March 2016 to see the shield when it was on loan to the National Museum of Australia (‘NMA’) as part of the Encounters exhibition. Kelly had grown up hearing elders in his community speak about his ancestors being there the day Cook landed. As an adult he traced his family tree and found that he is a direct descendant of one of the two Gweagal men who stood on the shoreline as Cook approached. On the final day of the NMA exhibition, Kelly staged a protest, asserting that the shield belonged to his ancestor, that the British had stolen it and that it must be returned to its rightful owners. In making this protest, Kelly became part of a strong and diverse group of Aboriginal activists, artists and academics making the point that the on-going non-consensual possession of Aboriginal artefacts by white cultural institutions is not only based on racist theft, but is also a denial of Aboriginal sovereignty.

The dispute over this shield goes well beyond questions of individual ownership and genealogy and to the heart of British white supremacy established at the genocidal expense of Aboriginal Australia.

Whatever conclusions about the shield’s provenance are reached by the British Museum and its invited experts, the fact remains that this shield is an Aboriginal object in the possession of an institution whose entitlement to it remains grounded in the racist notions of cultural and intellectual superiority which saw it displayed in its cabinets in the first place. So long as the shield remains in the possession of the British Museum, its full educative capacity and ‘true identity’ will remain trapped in the discourse of the latest knowledge preferred by the heirs of its colonial captors.