The Moai Stones

MOAI STONES

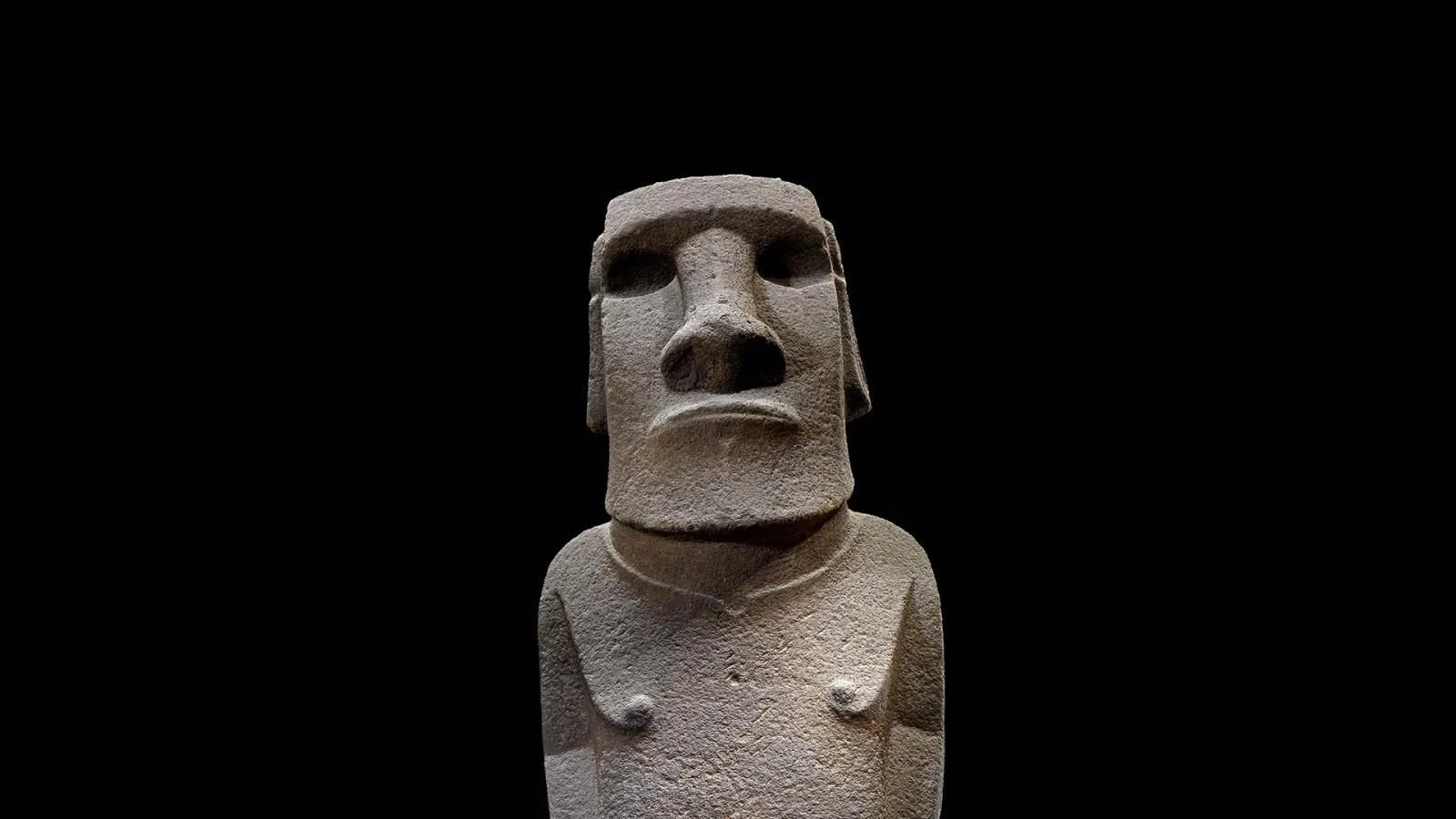

The Museum cares for two large stone moai from Rapa Nui (Easter Island): Hoa Hakananai’a and Moai Hava. Moai are megalithic statues often placed upon ahu (ceremonial platforms). They are said to be the aringa ora, the living faces of the ancestors.

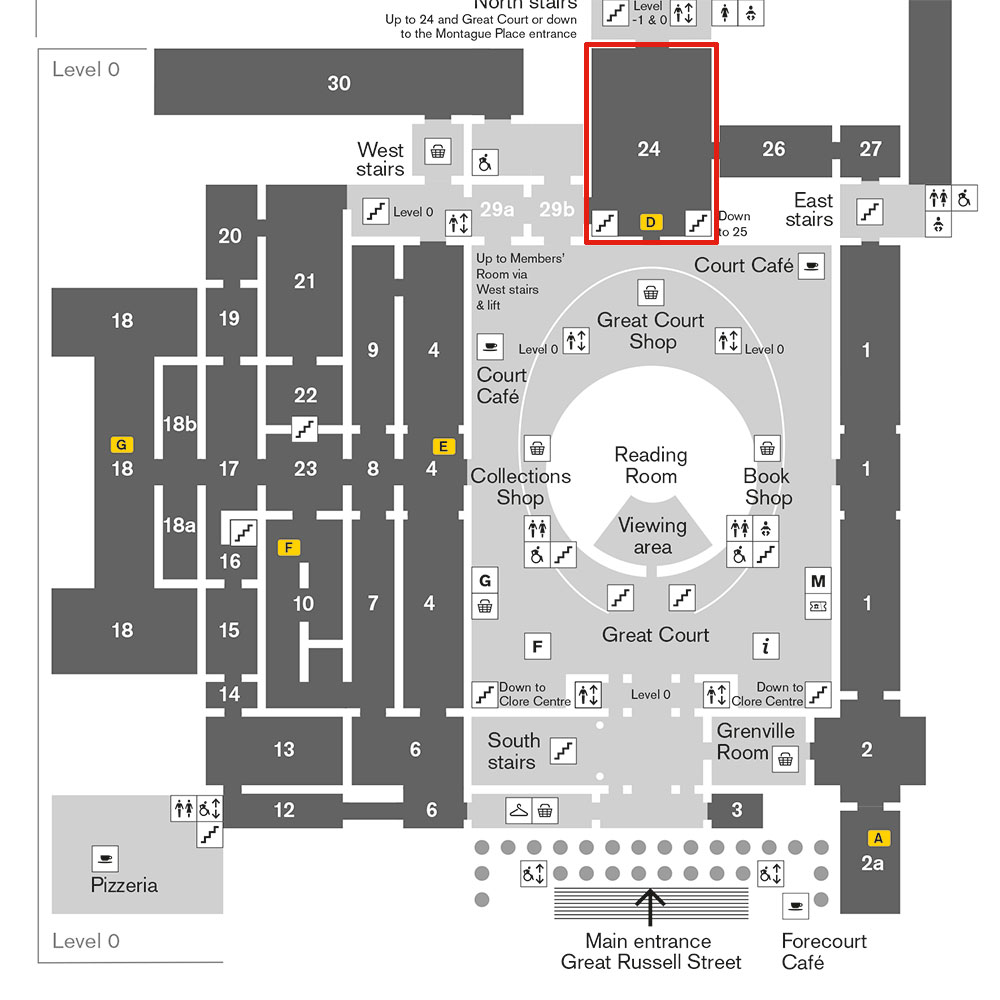

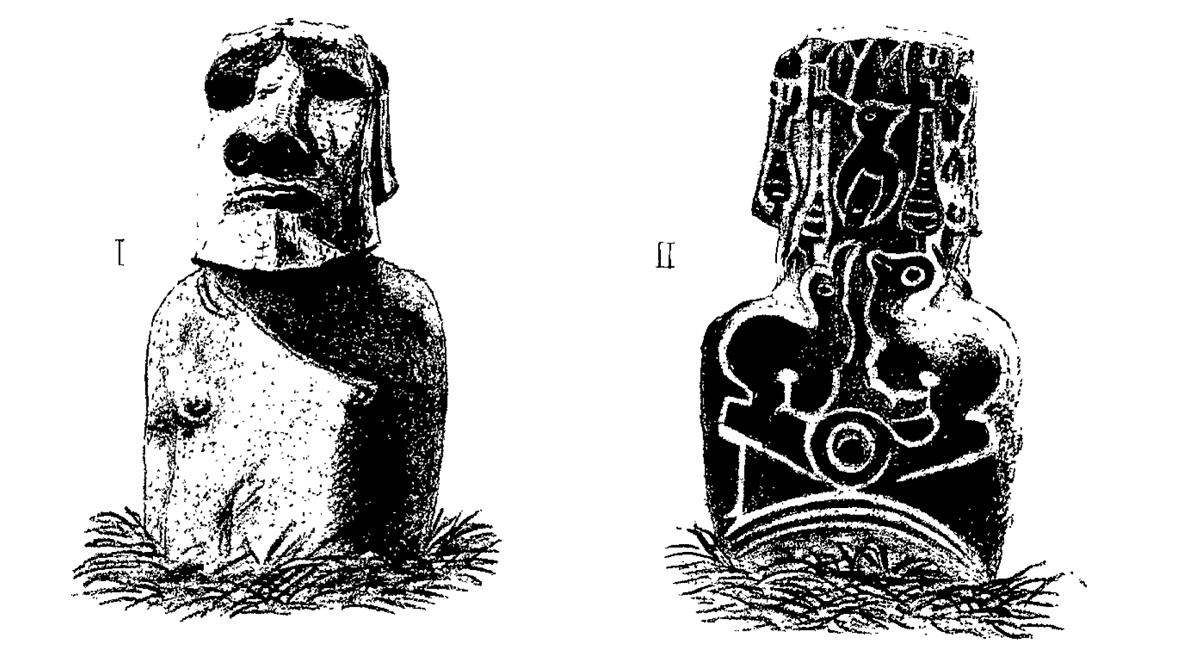

Hoa Hakananai’a (meaning ‘lost, hidden, or stolen friend’) is carved from basalt and dates from about 1000–1200. The back of the statue features intricate petroglyphs associated with the tangata manu, or birdman religion. This moai is on permanent display in the Museum in Room 24, as part of the Living and Dying display.

Where are they from?

Hoa Hakananai’a and Moai Hava originate from Rapa Nui (Easter Island), also referred to as Te Pito o Te Henua (‘the navel of the World’), and settled by skilled Polynesian navigators around 1000. In 1888, the island was annexed by Chile.

In the mid-1800s, Hoa Hakananai’a was buried up to his shoulders in a house named Taura Renga at the ceremonial village of Orongo, near Rano Kau. It is believed that this house was the second placement of this moai, and that he could have previously stood on an ahu-like structure (ceremonial platform) before his ritual function changed. Inside the ceremonial house at Orongo, the statue was more strongly associated with the tangata manu, or birdman religion, which developed around 1400, well after Hoa Hakananai’a was carved. Orongo was the epicentre of this new ritual practice establishing a competition among Rapanui chiefly groups to obtain the first egg of the sooty tern from the nearby islet of Motu Nui. The chiefly victor became the tangata manu (birdman) and represented the patron god of the royal lineage for one year.

Moai Hava was buried in the ancient gathering place of clans and in proximity with burial sites, in an area now known as Mataveri.

How did they come to be in the possession of the British Museum?

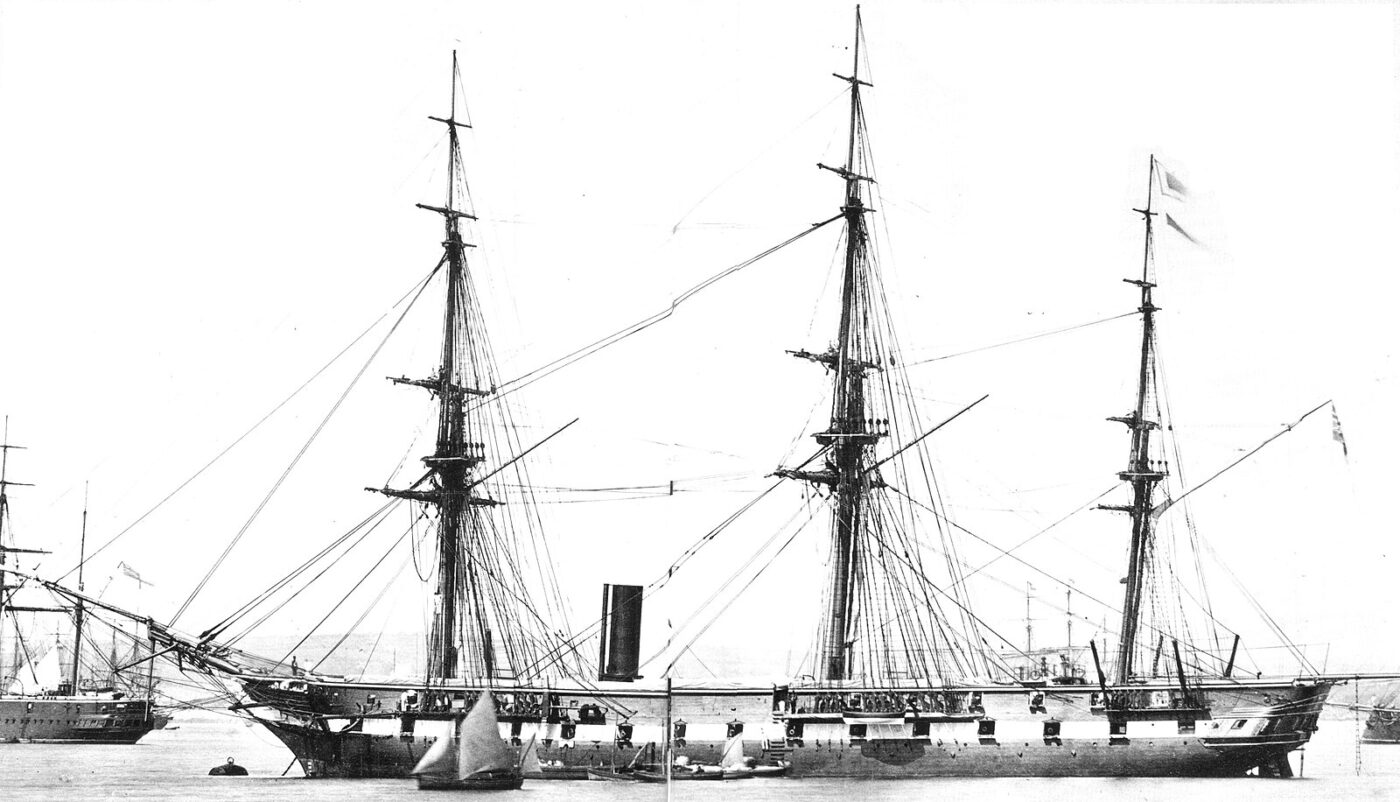

Known as Hoa Hakananai’a, it was removed from Easter Island by the naval crew of HMS Topaze in November 1868. HMS Topaze was sent into South Pacific seas in the late 1860s on a surveying mission. Among all the documentation that has survived from this voyage, there is no evidence that the expedition was organized with the prior intent of obtaining a moai statue for the British Museum. This lack of premeditation was common with diplomatic gifts, and to a lesser extent even with military plunder.

The situation that greeted the crew of the Topaze on Easter Island was grim, to say the least. Exposure with the European World of germs and guns constituted devastation on an epic scale. Once home to roughly 3,000 people, Easter Island was now nearly empty: just over one hundred people remained.

Over the previous decades, it had become abundantly clear that no indigenous Polynesian island or even an entire archipelago could stand alone against the encroachment of the outside world. A seismic shift in Pacific politics was underway. One by one every island kingdom had fallen under Western control or influence: the Society Islands, New Zealand, Hawaii, the Marquesas, the Tuamotus and Samoa.

This was the political backdrop to the arrival of HMS Topaze in November 1868. Few islanders – indigenous or Western – would have held any illusions about the future of Easter Island.

As was common in nearly all cross-cultural encounters in the Pacific over the previous century since Cook, the islanders were eager to trade for foreign goods. The captain of HMS Topaze, Commodore Richard Powell, lent carpenters, nails and planks to Dutrou-Bornier (who was attempting to build a schooner to sail to Tahiti) and distributed food and other provisions to the native community.

The islanders responded by offering in return what meagre resources they had: wooden crafts, song and dance performances, and – if a century of past precedent is any guide – sex.

Over the next few days, indigenous guides led different parties of the crew to the two moai statues that would eventually be taken back to London.

One participant in the transport of Hoa Hakananai’a across 5 kilometers (3 mi.) of rough terrain noted the availability of ‘many willing hands’, an apparent reference to the approximately sixty indigenous islanders who lent their assistance to the statue’s removal. In addition, the islanders were said to have ‘cheered’ when the statue was floated out to the ship at anchor and successfully hoisted aboard. The event was so memorable that one islander named Tepano even had the scene tattooed on his arm, while another woman named Veriamu could still recall – decades later – the song sung by the English sailors as they transported the heavy megalith.

(The fact that the name ‘Hoa Hakananai’a’ literally means ‘stolen’ or ‘hidden friend’ in the local Polynesian dialect is unlikely to have constituted a moral judgement by islanders on the British removal, since the moai already bore this name when British officers were led to it – more likely this enigmatic name is a reference to an earlier unknown event in the statue’s prehistory.)

However, perhaps the most telling piece of documentation was a handwritten letter given to Commodore Powell upon his departure from Easter Island. It was a petition from the ruling council – four native chiefs, Dutrou-Bornier and a Catholic missionary named Gaspar Zumbohm – to the French ambassador in Valparaíso requesting that France annex the island as a protectorate. France rejected it – not only this one, but four additional petitions submitted over the next two decades.

These petitions provide useful context for the account of a French expedition in 1872 that found one attractive moai too heavy to load onto its ship. The solution was to saw its head off. Not only did the entire community witness this event, but they ‘dramatically participated in it’. Placed in its proper historical context, this ‘desecration’ is easy to understand. The moai, silent sentries who had stood watch over their clans for centuries, had failed to protect their descendants from near extinction in the modern world. As a result, these once sacred statues were not quite so sacred any more. Far better to turn them into silent diplomatic ambassadors that might encourage a powerful global empire to take Easter Island under its protective wing – a modern twist on a traditional symbol of native power. In the end, it was Chile, not France, that annexed Easter Island in 1888. But this unexpected turn of political fate should not distract us from an obvious conclusion: Hoa Hakananai’a and Moai Hava were presented to the crew of HMS Topaze as diplomatic gifts. Their function was much the same as the replica moai presented by the Chilean ambassador to American University 132 years later: both of them represented an acknowledgement of friendly relations in the present and a tangible investment in the possibility of an even more fruitful political relationship in the future.

A case of a diplomatic gift, one that was tendered freely, knowingly and in exchange for immediate or anticipated political favors.

Voyage to the moai of

Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

Moai, sacred ancestor figures of Rapa Nui

British Museum faces criticism of Moai

What has been requested?

In July 2018, a written request for the return of Hoa Hakananai’a on behalf of the people of Rapa Nui was made by the Council of Elders (Consejo de Ancianos), CODEIPA (Comisión de Desarrollo de la Isla de Pascua/Development Commission of Easter Island) and the municipality of Rapa Nui. The letter stated the intention by the co-signers to ‘initiate official talks with the United Kingdom to succeed in repatriating Moai Hoa Haka Nanai’a’ [sic], later including the second statue, Moai Hava. In addition, the letter contained a request for a meeting at the Museum, and an invitation to Rapa Nui to visit relevant sites.

Following this request, a delegation from Rapa Nui was invited to the Museum. This official visit by representatives of the Rapanui community took place in November 2018.

Status of discussions

While in London in November 2018, plans were made for a reciprocal visit to Rapa Nui by British Museum staff, to continue discussing the request. This visit took place in June 2019. British Museum staff were taken to see various cultural sites to better understand aspects of Rapanui culture, the significance of the statues, and the community’s aspirations and took part in a series of conversations about the moai. All parties involved at the time of the visit agreed to commit additional resources to strengthening the relationship between the Museum and the community, including through the development of a Memorandum of Understanding and through active collaborations with Rapanui colleagues.

In August 2019, the Museum welcomed a Rapanui group for a research visit in the collections. In 2020–21, while the COVID pandemic brought international travels to a halt, a programme dedicated to collections from Oceania (the Benioff Oceania Programme) focused research efforts on Rapa Nui in order to improve access to and documentation of associated collections, in conversation with Rapanui colleagues. In 2022, a staff member of the Father Englebert Anthropological Museum, Hanga Roa, Rapa Nui was hosted at the Museum for several weeks as a fellow of the Benioff Oceania Programme and the International Training Programme. In 2023, several Rapanui colleagues and collaborators were invited to the Museum, advising on international working groups and conducting research in archives and collections.

Continuing in 2023–24, Rapanui collaborators were involved in co-creating a soundscape offering for the Rapanui tao’a (treasures) at the Museum, including the two moai, Hoa Hakananai’a, and Moai Hava. This audio piece, composed of sounds recorded by the artists on Rapa Nui, aimed to act as a bridge between the Rapanui community and the Museum, attempting to shrink the space between the treasures and their home. These events have strengthened relationships with the Rapanui community and laid the foundation for further collaboration.

The British Museum’s position

The Museum recognises the significance of Hoa Hakananai’a and Moai Hava for the Rapanui community today, and acknowledges the impact of their removal from the island in 1868.

The Museum is developing a long-term relationship with the community of Rapa Nui, to bring staff time and resources to collaborative research and reinterpretation of the Rapanui collections for the benefit of the community and the wider world. We plan to continue developing mutually beneficial projects with artists, scholars and other community members in Rapa Nui.

Hoa Hakananai’a represents one of the world’s great traditions, and is a witness to the global significance of Rapanui culture. Its presence in London influences public understanding of the history of Rapa Nui, its people’s artistic achievements past, present and future, and the challenges faced by the community today. The strength of the British Museum collection is its breadth and depth which allows millions of visitors an understanding of the cultures of the world and how they interconnect – whether through trade, migration, conquest, peaceful exchange or other interactions – both in the past and today.