Assyrian Artifacts

Assyrian Artifacts, 1100-635

Iraq was part of the Ottoman Empire throughout the 19th century, and the government was content to allow foreign excavations and the removal of finds with little hindrance. Even in the 1870s excavators were often only regulated by a regime intended for mining operations, and had to pay a tax based on a proportion of the value of material removed.

Although a number of travelers and explorers had visited the Assyrian sites of Nimrud and Nineveh, they weren’t excavated until the mid-19th century, when a young British diplomat, Austen Henry Layard, started work at Nimrud. Layard’s remarkable discoveries at Nimrud included colossal winged bulls and carved stone reliefs from the Assyrian palaces, which attracted sponsorship from the British Museum. Layard moved his team to the main mound at Nineveh in 1847, where he discovered the ‘Palace Without Rival’, King Sennacherib’s great royal residence.

Arrangements were made with the Ottoman government to have the Assyrian sculptures shipped to Britain. Due to the size of the sculptures, this proved to be some task. Firstly, the sculptures were transported to the river Tigris, where they were loaded on rafts that sailed to the city of Basra in southern Iraq. From here they were placed on a steamship and taken to Bombay in India, before sailing around Africa to England, where they were finally transported to the British Museum. Layard’s discoveries caused a media sensation and captured the public imagination. This had a major impact on painting and applied arts, in the UK and beyond, during the second half of the nineteenth century, which led to a brief phase of ‘Assyrian revival’. The Assyrian sculptures at the British Museum largely remain today where they were first installed over 160 years ago.

Disputed Ownership

Many Assyrian artifacts, including those from Layard’s excavations, were acquired during a time when Britain was a major colonial power. The legality and ethical implications of these acquisitions are questioned.

Ottoman Authorization

While some argue that the Ottoman authorities, who controlled Iraq at the time, authorized the removal of artifacts, this is contested, especially by those who believe the Ottomans had no authority over Iraqi cultural heritage.

The Palace Decoration

of Ashurbanipal

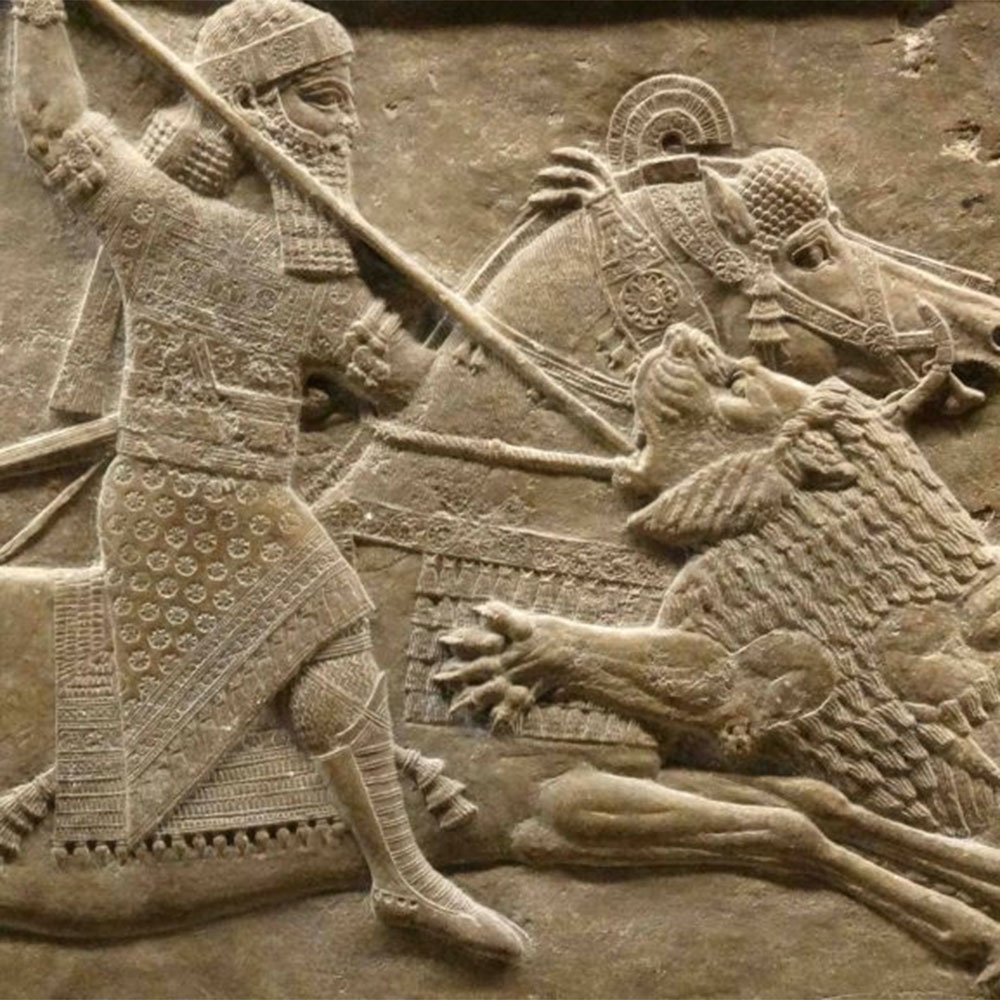

Ashurbanipal Hunting Lions

Iraq’s archaeologists rebuild historic Nimrud site ravaged by ISIS

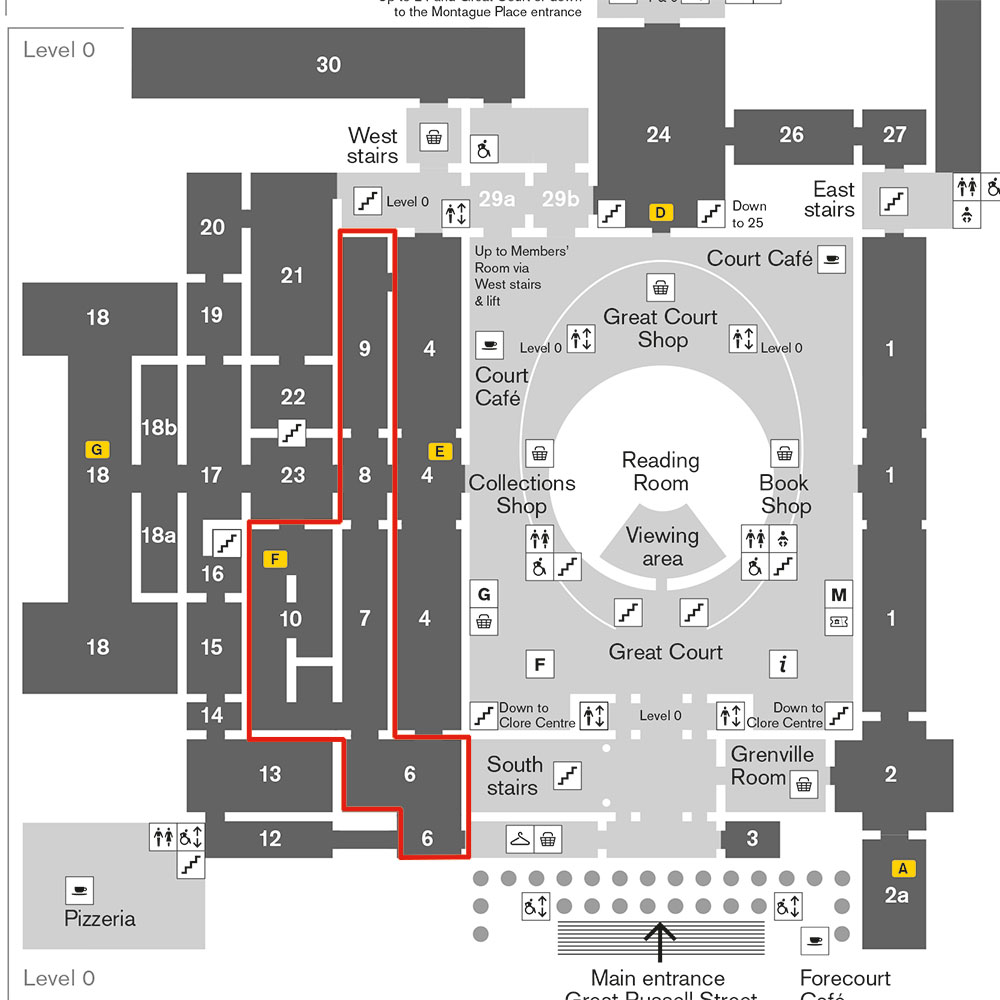

Rooms 6a-b, Assyrian Sculpture & Balawat Gates 1100–800 BCE

Large stone sculptures and reliefs were a striking feature of the palaces and temples of ancient Assyria (modern northern Iraq).

Visit Rooms 6a and 6b to see two colossal winged human-headed lions that flanked an entrance to the royal palace of King Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) at Nimrud. Plus, see a gigantic standing lion that stood at the entrance to the nearby Temple of Ishtar, the goddess of war.

These sculptures are displayed alongside fragments and replicas of the huge bronze gates of Shalmaneser III (858–824 BCE) from Balawat.

A Black Obelisk also on display shows the same king receiving tribute from Israel and is displayed with obelisks and stelae (vertical inscribed stone slabs) from four generations of Assyrian kings.

Rooms 7-8, Assyria: Nimrud 883–859 BCE

The Neo-Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BCE) built his magnificent Northwest Palace at Nimrud.

The site of Nimrud is located on the Tigris River in modern-day Iraq. Interior decoration of the palace featured a series of remarkable carved stone panels.

The detailed reliefs on display in Rooms 7–8 originally stood in the palace throne-room and in other royal apartments. They depict the king and his subjects engaged in a variety of activities. Ashurnasirpal is shown leading military campaigns against his enemies, engaging in ritual scenes with protective demons and hunting, a royal sport in ancient Mesopotamia.

Room 9, Assyria: Nineveh 704–692 BCE

Nineveh was the capital of the powerful ancient Assyrian empire, located in modern-day northern Iraq.

Sennacherib was the King of Assyria from 704–681 BCE and was famous for his building projects. The rooms and courtyards of his Neo-Assyrian Southwest Palace at Nineveh were decorated with a series of detailed carved stone panels. Many of these stone panels are on display in Room 9. The panels depict a variety of scenes, including the transport of huge sculptures of human-headed winged bulls (lamassu) that weigh up to 30 tons and were intended for the main entrances to the palace.

These illustrations provide an insight into ancient quarrying and transport techniques, as well as Sennacherib’s keen interest in his building projects. Other panels on display depict the king’s military campaigns.

Rooms 10a-c, Assyria: Lion hunts, Siege of Lachish and Khorsabad 710–635 BCE

Visit Rooms 10a, 10b and 10c explore about 50 years of Assyrian history, in what is modern-day Iraq.

Split across three rooms, these galleries display life during this period in Assyrian culture. On display are lion hunting reliefs, the siege of the city of Lachish and scenes from inside the palace of King Sargon II at Khorsabad.

Visitors to Room 10a are greeted by a pair of colossal human-headed winged bulls. Intended as a supernatural guardians, these gigantic figures guarded the palace of King Sargon II at Khorsabad, and were intended to deter evil of all kinds from entering.

A full and characteristic set shows the campaign leading up to the siege of Lachish in 701 BCE; it is the “finest” from the reign of Sennacherib, from his palace at Nineveh and now in the British Museum.

Another famous sequence there shows the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal, in fact the staged and ritualized killing by King Ashurbanipal of lions already captured and released into an arena, from the North Palace at Nineveh. The realism of the lions has always been praised, and the scenes are often regarded as “the supreme masterpieces of Assyrian art”, although the pathos modern viewers tend to feel was perhaps not part of the Assyrian response.

The name Ashurbanipal can hardly be counted among the most famous when it comes to ancient leaders. Against the likes of Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Cleopatra and many others, he may struggle, in the Western world at least, to get picked out of a line up.

Even Gareth Brereton, the curator of a British Museum exhibition about him and his often-overlooked Assyrian Empire – I am Ashurbanipal: King of the World, King of Assyria, which ran from late 2018 until early 2019 – says that he is “the greatest king you’ve never heard of”.

In his day, Ashurbanipal was the most powerful person on Earth. As the dominant force in seventh-century-BC Mesopotamia, the crucible of civilizations, he furthered Assyria’s reach beyond what had been achieved in the previous two millennia. And he used his power to build a vast library of texts from across his empire – the oldest of its kind surviving – that has bestowed a wealth of knowledge about this ancient world and its peoples.

Destruction & Rebuilding

When the Islamic State militant group captured parts of Northern Iraq in 2014, it declared war on the ancient city of Nimrud, taking sledgehammers to the ancient site, drilling holes in its carvings, and finally blowing the entire place up. Though later reclaimed by Iraqi forces in 2016, the ruins have been forever changed, the victim of massive destruction. By the time Nimrud was retaken, around 90% of the excavated part of the city had been destroyed entirely. Every major structure had been damaged, the Ziggurat of Nimrud had been flattened, only a few scattered broken walls remained of the palace of Ashurnasirpal II, the Lamassu that once guarded its gates had been smashed and scattered across the landscape.

When the Islamic State captured parts of Northern Iraq in 2014, it declared war on the ruins of Nimrud, releasing this video of ISIS militants taking sledgehammers to the ancient site, drilling holes in its carvings, and finally blowing the entire place up.

When ISIS took the town, they also destroyed Sheik Khalid’s home and killed 40 of his family members, including two brothers. But he says he rarely cried, until he saw this ISIS video.