TATE MODERN | MAP | FREE – Check on Free Tours, Late Nights | DOWNLOAD MAP

One of the exciting things for me about art is the ongoing dialogue from the past to the future. Art is never in a vacuum – the future relies entirely on the past for inspiration. And yet time is fluid and relative. It is fascinating to see the artists at the Tate Modern poke at each other, rebel against one another, display honor and reverence for one another: they retreat, they roar, they respond to the world around them so differently and yet are still products of their time.

It is also one of the best people-watching spots in all of London.

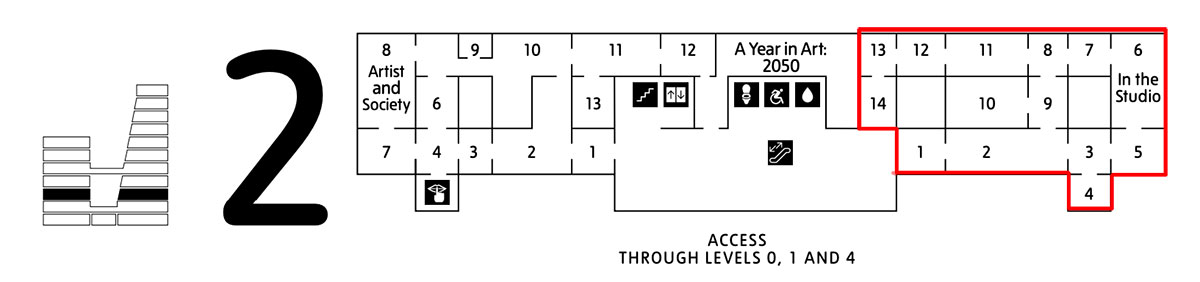

All the works on this tour are in the Natalie Bell Building Level 2 East, In the Studio Galleries 1-14 – except for the last 2 works, Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone and Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain.

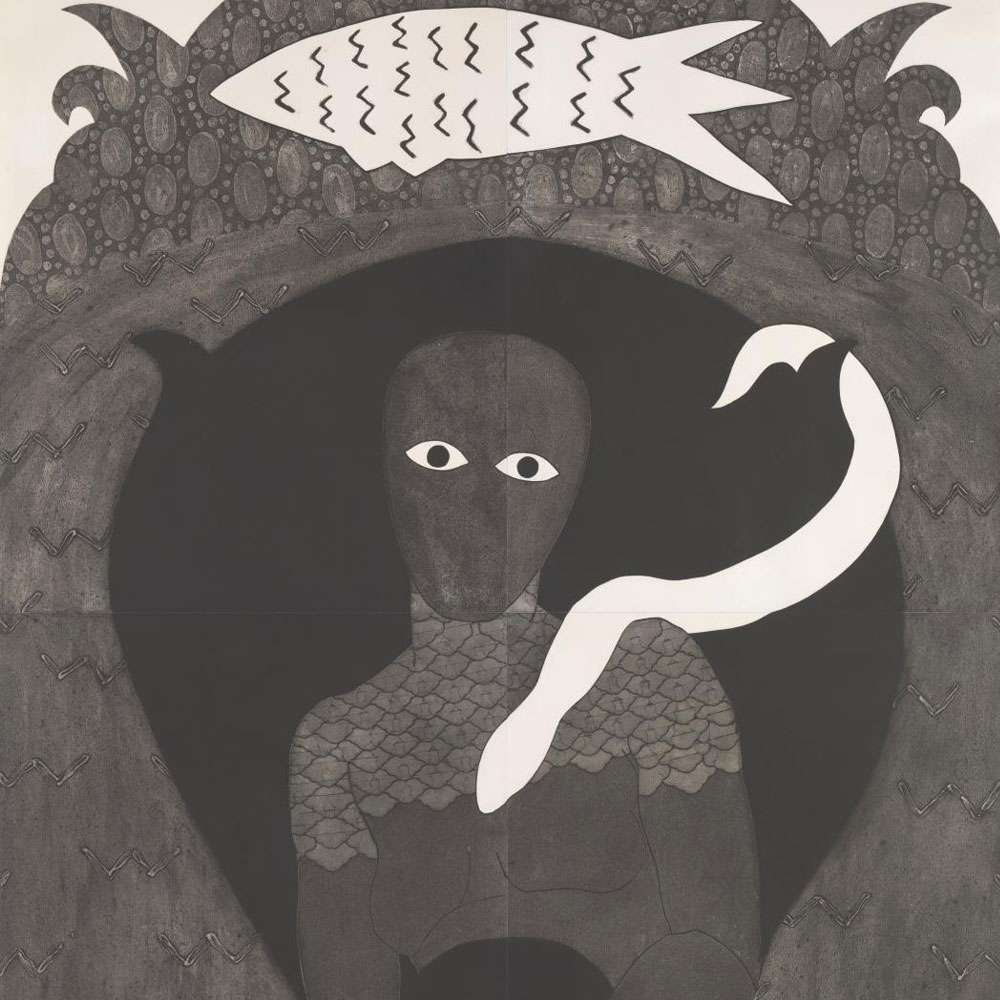

Belkis Ayón & Sandra Vásquez de la Horra

These artists have used paper in unexpected ways to create prints and sculptures. The artworks of the two artists in this room draw upon specific indigenous belief systems to explore the position of women in society and in nature.

Belkis Ayón (1967–1999) was a Cuban printmaker who specialized in a printmaking process called collography.

Sandra Vásquez de la Horra (born 1967) grew up during General Augusto Pinochet’s 17-year military regime in Chile, later relocating to Germany. Since 1997, she has developed her own form of sculptural drawing.

Clarinet and Bottle of Rum on a Mantelpiece, 1911

Georges Braque, 1882-1963 | ROOM 2, Studio Practice

A horizontal clarinet lies on top of a mantelpiece at the centre of this playful, geometric work. In front stands a bottle with the characters RHU, the first three letters of the French word for rum. The word VALSE (waltz) indicates sheet music, reinforced by fragments of treble and bass clefs found throughout the image. A scrolled form in the lower right could represent part of the mantelpiece, or a violin-head. Braque painted this during a summer he spent with Picasso in the Pyranees. They worked together depicting similar scenes and objects in the same style.

Seated Woman with Small Dog, c.1939

Meraud Guevara, 1904–1993 | ROOM 2, Studio Practice

The woman in this painting dominates the steep, angled space. She would not fit in the interior if she were to stand. This creates a sense of uncertainty for the viewer. Guevara made a number of precise and realistic paintings of women, in which they dominate the space. This gives the viewer a strange and uneasy perspective. Here, a sense of mystery is suggested by the imaginary view. This is achieved by placing the room high above the landscape, the open doorway behind, and the strange, but deliberate, flash of orange beside the door.

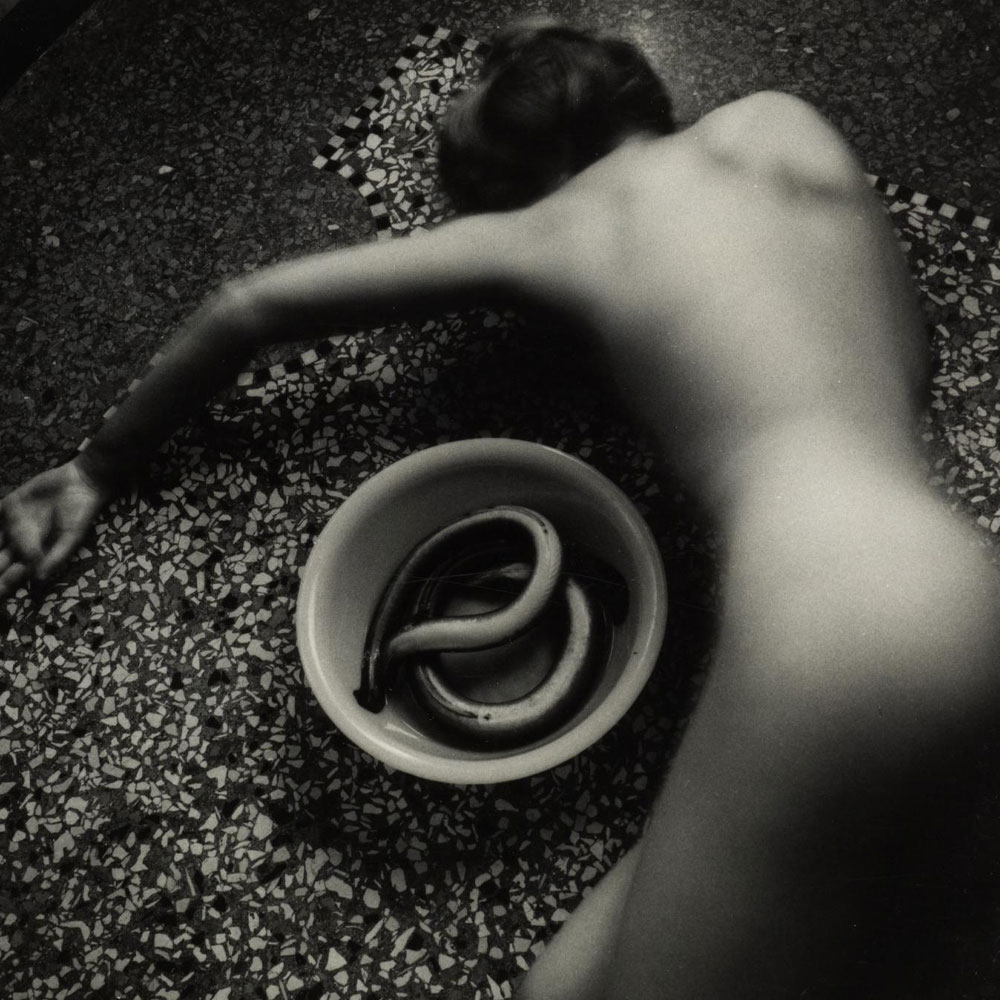

Untitled, from Eel Series, Venice, Italy, 1978

Francesca Woodman, 1958–1981 | Room 3, ARTIST ROOMS: Francesca Woodman

Woodman lies naked, in a vulnerable state, the curve of her body echoing the curved form of the eel. She has printed several similar versions of this image with her body on either side of the eel. While Woodman was studying in Rome between 1977 and 1978 she came into contact with the Symbolist work of Max Klinger, whose influence can be seen in this series. The image is sexually charged, yet in placing herself on both sides of the camera Woodman hovers between being in control and being defenceless, exploring the ways in which femininity can be portrayed. The photograph is not a self-portrait in the conventional sense, as it explores the possibilities of representation, instead of revealing the artist’s identity.

Cadeau, 1921, editioned replica 1972

Man Ray, 1890–1976 | Room 5, International Surrealism

By adding a row of nails, Man Ray transformed a household flat-iron into a new and potentially threatening object. The nails and burning metal suggest a violent eroticism at odds with the work’s title, the French word for ‘gift’. The original version, given to the composer Erik Satie, was lost but became well-known through Man Ray’s photograph of it. Although made at the height of Paris dada, Cadeau, like Man Ray’s other objects, anticipated the exposure of hidden desires found in subsequent surrealist objects.

The Entire City, 1934

Max Ernst, 1891–1976 | Room 5, International Surrealism

A crumbling city looms oppressively below the ring-shaped moon. Ernst made a whole series of such works. The imagery may reflect his pessimism as Nazism took hold in his native Germany. The ruined cityscape was created using a technique that Ernst called ‘grattage’ (scraping). It involved placing the canvas over planks of wood or other textured surfaces, then scraping paint across it. The shapes that emerged formed the basis of the image. Grattage was one of a number of techniques that Surrealist artists explored as a way of letting a chance element into their work.

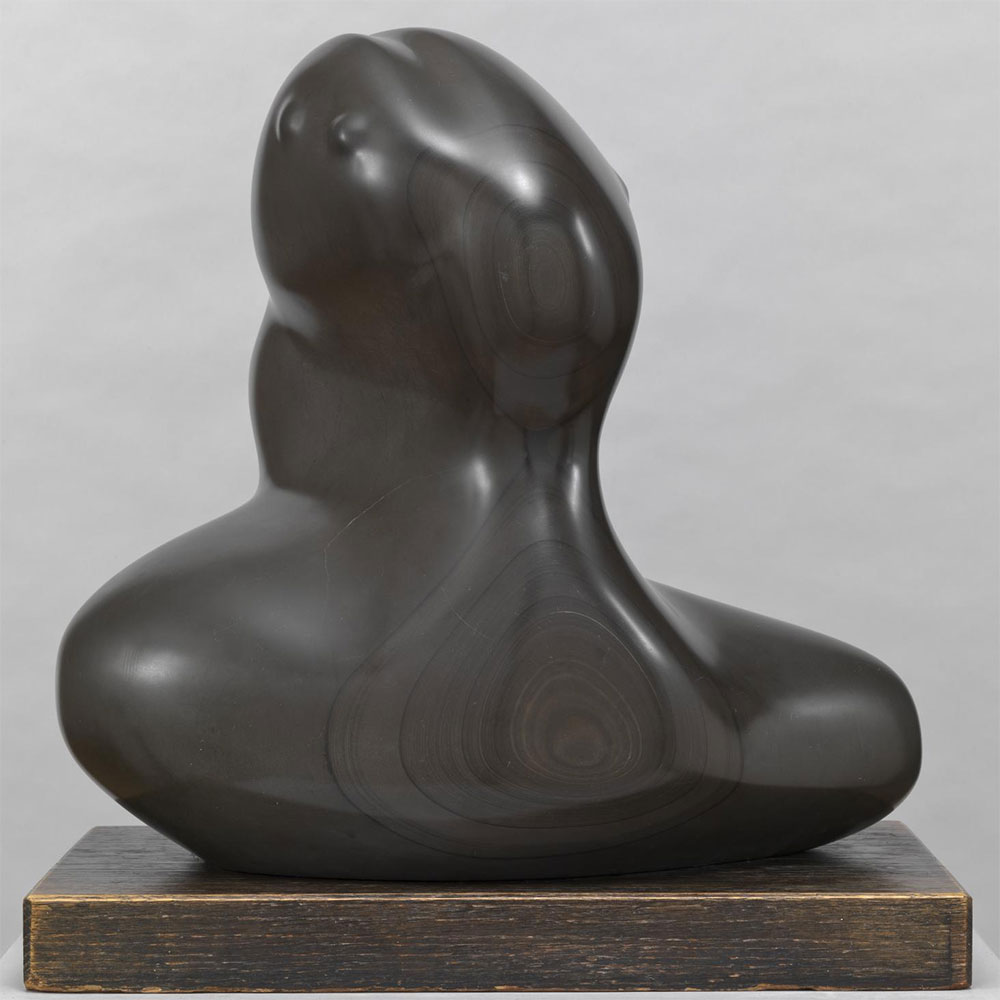

Composition, 1932

Henry Moore OM, CH, 1898–1986 | Room 5, International Surrealism

Moore drew inspiration from many sources, including natural forms and ancient sculptures. He also responded to the work of other artists working at the time. This sculpture is both organic and abstract. But its form and structure also link it to traditional portrait busts. This reflects Moore’s belief that ‘all the best sculpture I know is both abstract and representational at the same time’. Composition is an example of his radical inventiveness. Moore argued that surrealism and abstraction were not in conflict. He wrote of the importance of the ‘nonlogical, instinctive, subconscious part of the mind’ in his artistic process.

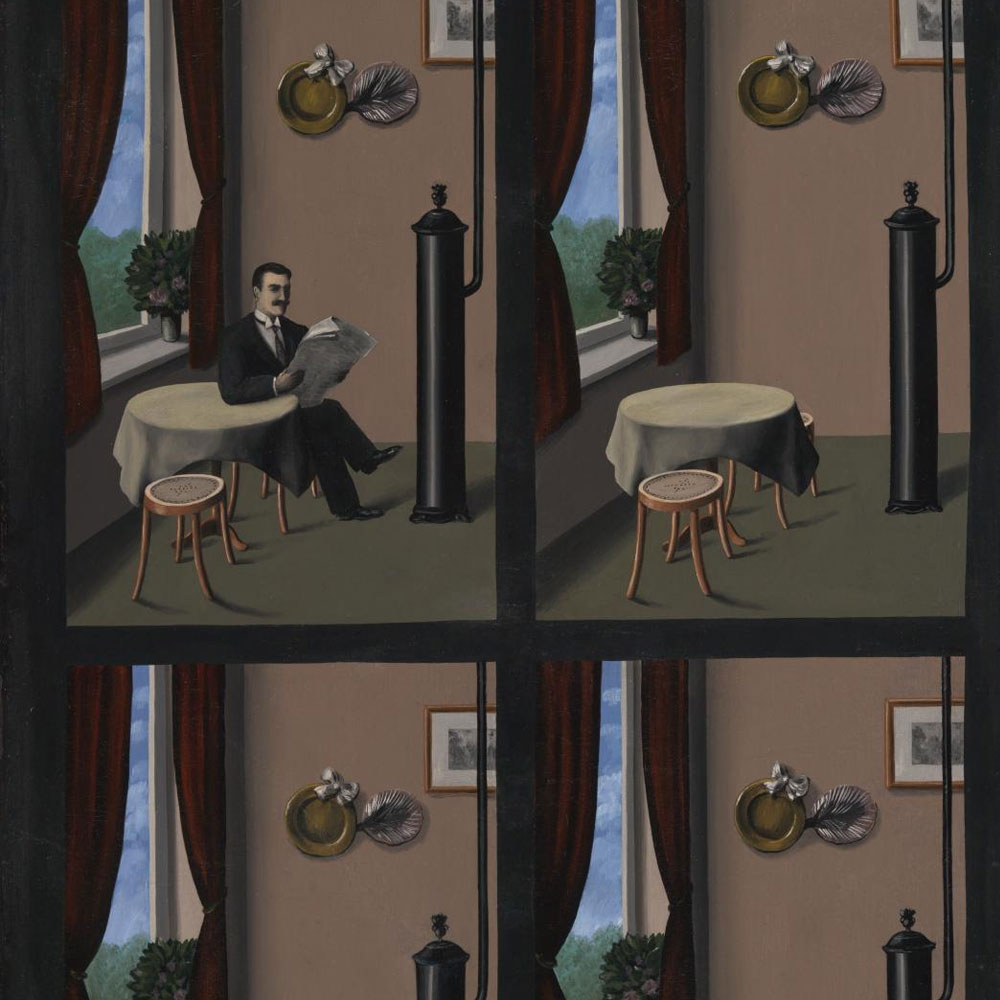

Man with a Newspaper, 1928

René Magritte, 1898–1967 | Room 5, International Surrealism

Woodman lies naked, in a vulnerable state, the curve of her body echoing the curved form of the eel. She has printed several similar versions of this image with her body on either side of the eel. While Woodman was studying in Rome between 1977 and 1978 she came into contact with the Symbolist work of Max Klinger, whose influence can be seen in this series. The image is sexually charged, yet in placing herself on both sides of the camera Woodman hovers between being in control and being defenceless, exploring the ways in which femininity can be portrayed. The photograph is not a self-portrait in the conventional sense, as it explores the possibilities of representation, instead of revealing the artist’s identity.

Three Symbols 1930

Eileen Agar, 1899–1991 | Room 5, International Surrealism

This painting includes structures from three eras: a Greek column, a Gothic cathedral (Notre Dame) and a modern bridge. Agar claimed that this flight of the imagination was the first work in which she began to move towards a more surrealist style. She and her future husband, the writer Joseph Bard, were living in Paris at this time. It was there that they met André Breton and Paul Eluard, who, she later recalled, were among the poets and painters giving the ‘kiss of life’ to surrealism, ‘that sleeping beauty troubled by nightmares’.

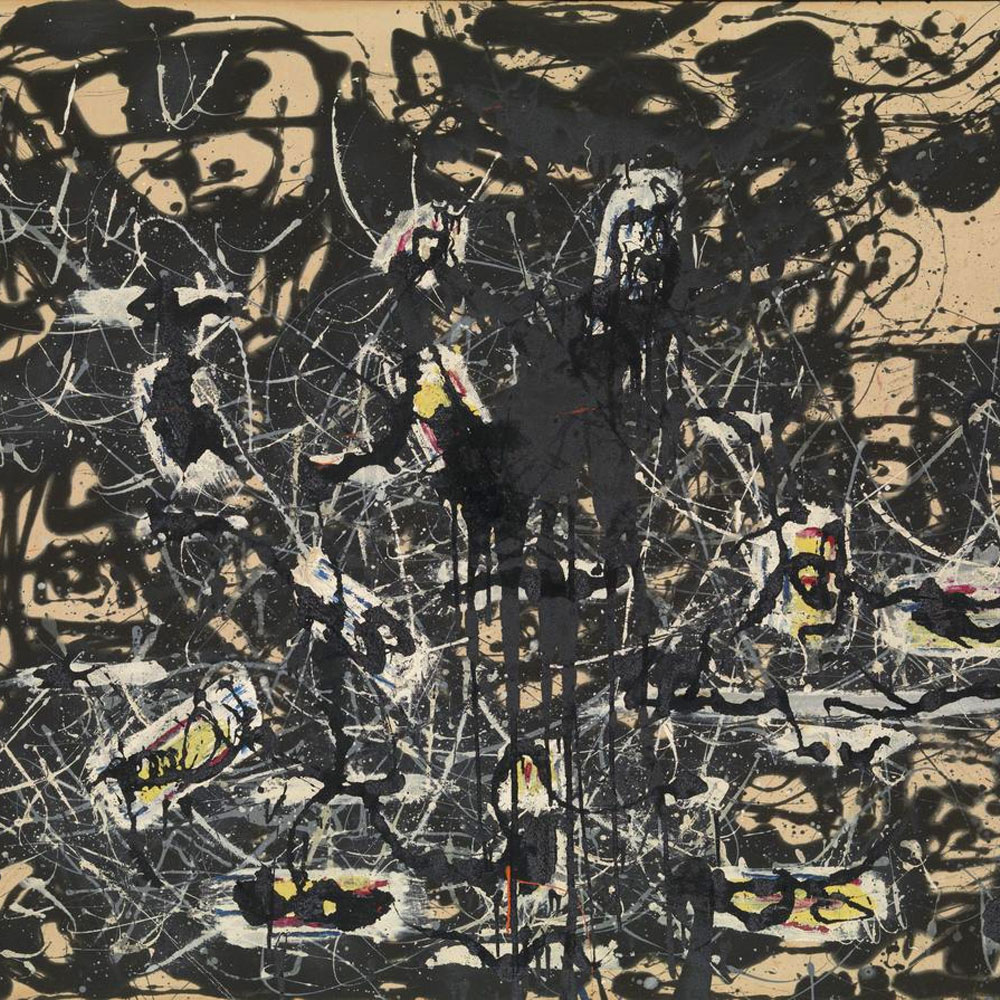

Yellow Islands, 1952

Jackson Pollock, 1912–1956 | Room 6, The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

‘When I am painting I am not much aware of what is taking place’, Pollock said in 1947. By dripping and pouring paint, he was able to work in a free and intuitive way, his thoughts and feelings finding direct expression in the rhythmic patterns he created. Pollock began this painting by pouring black paint onto the canvas, over which he added areas of yellow and crimson with a brush. He then lifted the canvas upright while the paint was still wet, allowing it to sag and run.

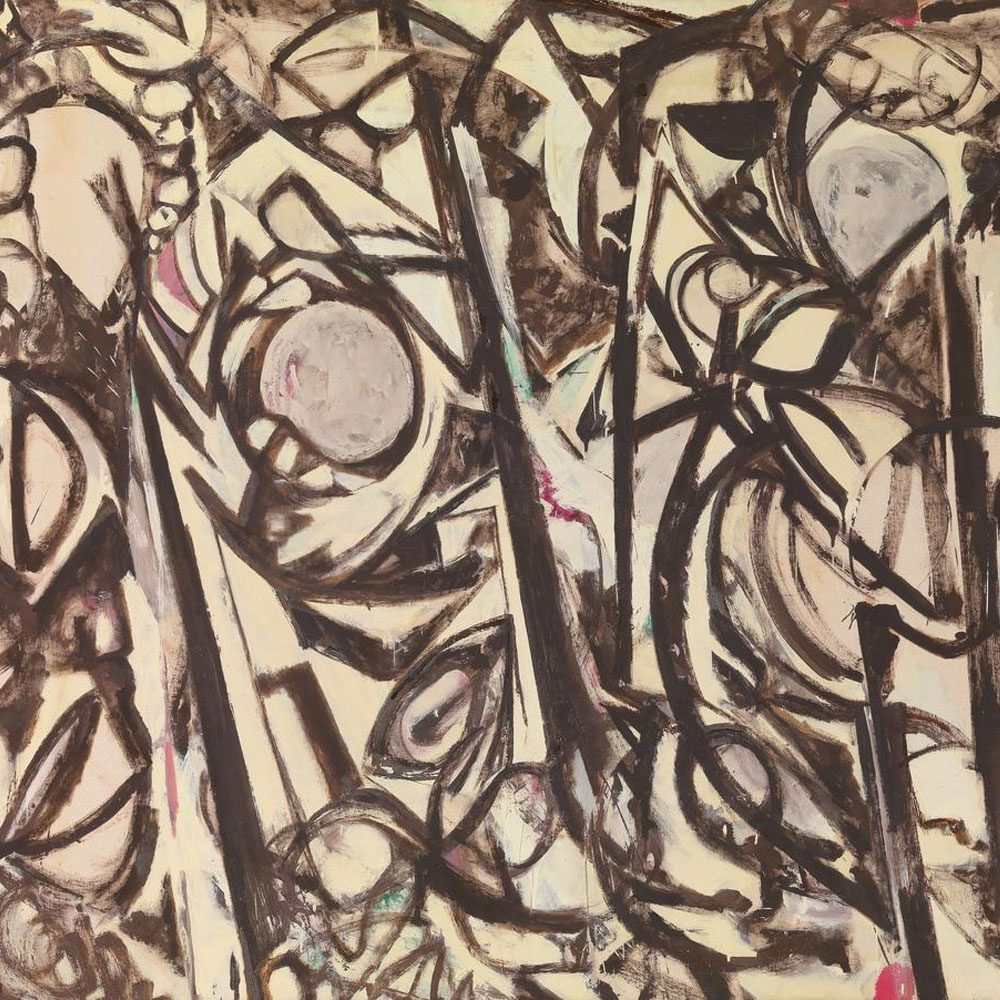

Gothic Landscape, 1961

Lee Krasner, 1908–1984 | Room 6, The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Although this is an abstract painting, the thick vertical lines that dominate its centre can be seen as trees, with thick knotted roots at their base. It was probably this that led Krasner to call the painting Gothic Landscape, several years after completing it. Krasner was married to the artist Jackson Pollock. Gothic Landscape was made in the years following his death from a car crash in 1956. It belongs to a series of large canvases whose violent and expressive gestural brushstrokes can be read as a reflection of her grief.

Ships in the Dark, 1927

Paul Klee, 1879–1940 | Room 7 & 8, The Shape of Words

Paul Klee was a Swiss-born German artist. His highly individual style was influenced by movements in art that included expressionism, cubism, and surrealism.

He and his colleague, Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, both taught at the Bauhaus school of art, design and architecture in Germany. His works reflect his dry humor and his sometimes childlike perspective, his personal moods and beliefs, and his musicality.

Iva, 1973

Joan Mitchell, 1925—1992 | Room 9, ARTIST ROOMS: Joan Mitchell

Emotion, nature and physical expression collide in this abstract painting.

Iva is named after Mitchell’s black and tan German Shepherd dog. In a 1974 interview, Mitchell declared of Iva: ‘She’s a total extension of me, or I am of her. I don’t know which way you want to put it.’

The beloved pet was gifted to the artist by Marguerite Maeght. Marguerite and her husband, the French art dealer Aimé Maeght, founded la Fondation Aimé and Marguerite Maeght, home to one of the largest collections of modern art in Europe.

Black on Maroon, 1959

Mark Rothko, 1903–1970 | Room 10, ARTIST ROOMS: Mark Rothko

I think the curation of Rothko’s is crucial to appreciation of his works. They are certainly best (and usually) displayed as a group.

In 1958, Mark Rothko was commissioned to produce a series of works for a restaurant in New York’s Seagram Building. He constructed a scaffold in his studio to match the site’s dimensions, allowing him to paint at scale. He said that his paintings, ‘are involved with the scale of human feelings, the human drama, as much of it as I can express’. The resulting works were much darker in mood than Rothko’s previous paintings. The bright and intense colours of his earlier canvases shifted to maroon, dark red and black. In 1960, after more than two years of work on the project and with a studio of completed paintings, Rothko withdrew from the commission. He felt the exclusive environment of the restaurant was an inappropriate setting for his artworks. He later presented the series to Tate.

Cage 1 – 6, 2006

Gerhard Richter, born 1932 | Room 11, ARTIST ROOMS: Gerhard Richter

The six paintings in this room were conceived by Gerhard Richter as a coherent group, named after the American experimental composer John Cage.

The Cage paintings are named after American minimalist and experimental composer John Cage, whom Richter greatly admired and to whose music the artist listened during the period he was making these paintings in 2006. Richter first encountered Cage in the 1960s at a performance given by the composer at the Düsseldorf Academy, where the artist was studying. Cage performed a piece in which he wrote with a microphone attached to a pen so that the scratching sound of the pen moving across the surface of the paper was transmitted. There are no direct links between any particular work in this series and any piece of music by Cage. However, Richter has long been interested in Cage’s ideas about ambient sound and silence, as well as his controlled use of chance procedures in musical composition.

The Snail, 1953

Henri Matisse, 1869–1954 | Room 12, Painterly Gestures

After 1948, Henri Matisse was confined to bed due to ill health. Though he could no longer paint, he produced many works by cutting or tearing shapes from paper painted in bright colours. An assistant then pasted the cut-outs on a white sheet following his instructions. Matisse found this technique liberating: ‘Instead of drawing the outline and putting the colour inside it … I draw straight into the colour.’ Matisse got the idea for this composition while drawing a snail. ‘I became aware of an unrolling, I found an image in my mind purified of the shell, then I took the scissors.’

Dark Strokes Hope, 1971

Joan Snyder, born 1940 | Room 12, Painterly Gestures

Between 1969 and 1972 Snyder created a series of ‘Stroke Paintings’. These feature arrays of distinct brushstrokes of various kinds and colours, in this work also including a handprint. ‘I was interested in process and I wanted to show the raw canvas… the gesso… the first layer of paint. I wanted to be able to see all those things in one painting… the anatomy of that painting, of how it evolved.’ Synder’s approach challenges us to look at painting at a slower pace, to follow the sequence of her strokes like a narrative text or a piece of music.

Marilyn Diptych, 1962

Andy Warhol, 1928–1987 | Room 14, In the Conservation Studio: Andy Warhol

In August 1962, Andy Warhol started experimenting with screenprints in his New York studio. When the actor Marilyn Monroe died the same month, Warhol was shocked by her death. He found a publicity photo of Monroe from the 1953 film Niagara, taken by the photographer Gene Kornman. Cropping her face, Warhol made a series of graphic screenprints based on the portrait. He painted over some of them by hand, then reprinted Monroe’s face on top of the color. Originally two separate pieces, Marilyn Diptych was first purchased by art collectors Burton and Emily Tremaine. Together, the mask-like depictions of Monroe could hint at the experiences of a life led inside and outside the celebrity spotlight.

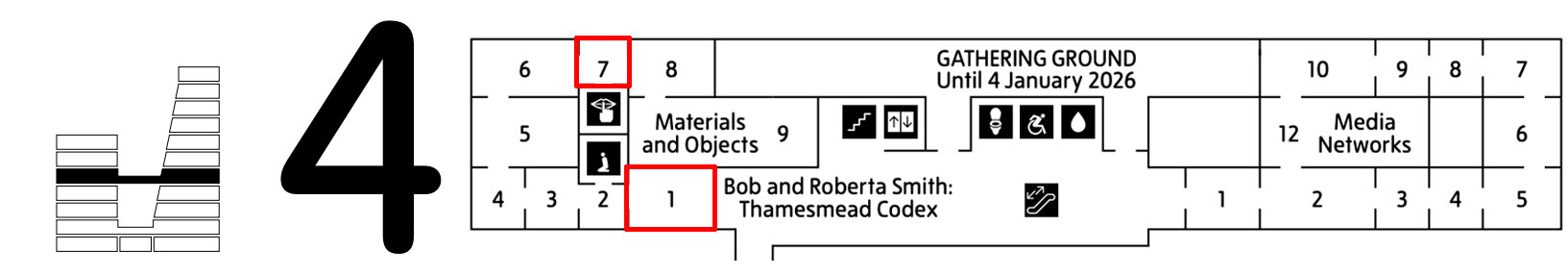

Lobster Telephone, 1938

Salvador Dalí, 1904–1989 | Room 1, Materials and Objects: Salvador Dalí & Robert Zhao Renhui

This is a classic example of a Surrealist object, made from the conjunction of items not normally associated with each other, resulting in something both playful and menacing. Dalí believed that such objects could reveal the secret desires of the unconscious. Lobsters and telephones had strong sexual connotations for Dalí. The telephone appears in certain paintings of the late 1930s such as Mountain Lake (Tate Gallery T01979), and the lobster appears in drawings and designs, usually associated with erotic pleasure and pain. For the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Dalí created a multi-media experience entitled The Dream of Venus, which consisted in part of dressing live nude models in ‘costumes’ made of fresh seafood, an event photographed by Horst P. Horst and George Platt Lynes. A lobster was used by the artist to cover the female sexual organs of his models. Dalí often drew a close analogy between food and sex. In Lobster Telephone, the crustacean’s tail, where its sexual parts are located, is placed directly over the mouthpiece.

Fountain, 1917, replica 1964

Marcel Duchamp, 1887–1968 | Room 7, Materials and Objects: Around the Fountain

Fountain is a readymade sculpture by Marcel Duchamp in 1917, consisting of a porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt”. In April 1917, an ordinary piece of plumbing chosen by Duchamp was submitted for the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists, to be staged at the Grand Central Palace in New York. When explaining the purpose of his readymade sculpture, Duchamp stated they are “everyday objects raised to the dignity of a work of art by the artist’s act of choice.”

The original work is now lost. This is a 1964 replica made from glazed earthenware and painted to resemble the original porcelain.