Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match c.1784–6 is a large oil painting by German-born artist Johan Zoffany. The cockfight represented in the foreground of the painting was based on an event held at the court of Asaf-ud-Daula, the Nawab Wazir (governor) of Awadh (Oudh) in Lucknow on 5 April 1784. The match was between Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula and Colonel John Mordaunt, an employee of the British East India Company (EIC). Mordaunt was the illegitimate and nearly illiterate son of the Earl of Peterborough. He had managed to be assigned to Warren Hastings and through him he was appointed head of security. His real role however included organizing entertainments.

Zoffany depicts the moment when two handlers have just released the birds. Behind them, to their left, Mordaunt stands upright in white evening dress. To his right, the Nawab appears to leap forwards enthusiastically. In contrast to Mordaunt’s upright, commanding posture, Asaf appears off-centre, his stature rounded, slightly bent forwards and eager. While Mordaunt’s appearance is bright, magnified by his white clothes, Asaf appears to be in shadow. The background details of the painting depict a stereotypical Indian landscape. Musicians are scattered throughout, squatting with their instruments, and an elephant with a carriage appears in the upper left corner. The crowd at the centre of the painting are engaged with the cockfight, while in the background groups of people gather in clusters, some holding birds, some appearing to engage in discussion.

The Nawab’s uncle, Salar Jung, stands between Asaf and Mordaunt, calculating a bet on his fingers. The two men dressed in bright blue and red clothing behind him are Asaf’s chief ministers, Hasan Reza Khan and Haidar Ali Khan. A key identifying the figures was published in 1794 (British Museum, London, accession no.1928,0417.35). The key is biased towards the European figures, identifying sixteen by name compared with only three Indian figures. In contrast to the British individuals, the features and expressions of many of the South Asian figures appear distorted to varying degrees, their expressions exaggerated almost to the point of caricature. However, sketches do exist for some of the sitters, including the Nawab (Royal Collection, London, RCIN 913286) and Hasan Reza Khan (private collection).

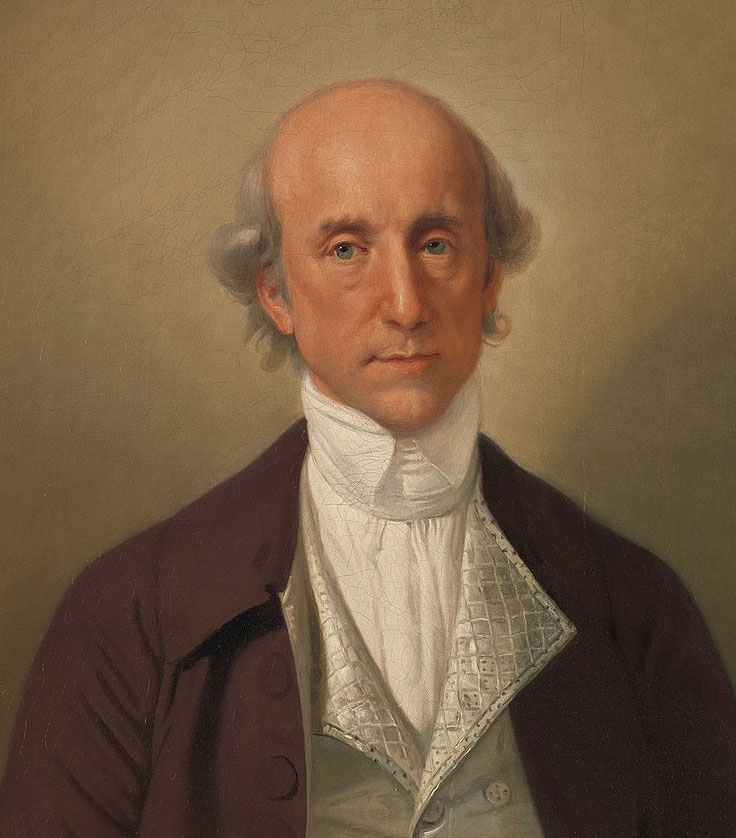

On and around the white sofa to the right, the European figures sit or stand, appearing confident and self-assured. Trevor Wheler, the EIC’s Assistant Resident, is seated and wears a dark coat; John Wombell, the EIC’s Accountant and Paymaster-General, is pictured smoking a hookah; below Wombell, seated on the white settee, Colonel Claude Martin is dressed in a red uniform. Standing under the awning behind Martin, and clad in red, is Colonel Antoine Polier, a Swiss officer who was engineer to the Nawab. (He was unlucky enough to arrive in the middle of the French Revolution and he was stabbed to death at Poitiers for being a noble.) Robert Gregory, Assistant to the British Resident at Lucknow, appears standing to the right holding a cockerel. To Gregory’s left stands a figure identified as ‘Mr. Orr’. Zoffany also included a self-portrait – towards the back, on the right, he sits with his arm over a chair, his expression nonchalant. The miniaturist Ozias Humphry stands beside him.

Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match expresses the many complex attitudes towards India and the East India Company that were held in Britain at the time. Positioned between Mughal Delhi and British-controlled Bengal, Lucknow had a Shiite Persian nominal ruler and mixed population of Hindus and Sunnis, as well as an increasing presence of EIC employees. Among them was Mordaunt, who was commander of the Nawab’s bodyguard and leader of court amusements, including cockfights.

Many Britons were critical of the suspected extravagance and corruption of EIC officials in India. Rather than questioning the premises of colonialism, these objections often contained the suspicion that India itself was a corrupting influence upon Europeans. Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula was often criticised, by both Indians and Europeans, for his perceived decadence. As Captain Robert Smith wrote in the 1830s regarding cockfighting, ‘This barbarous amusement is a particular favourite with the people of Lucknow and is as great a source of demoralisation here, as it is in every country where the custom prevails’ (quoted in Mildred Archer, India and British Portraiture 1770–1825, London 1979, p.148). It is likely that the painting would have provoked a similar judgment among a European audience, while providing an exoticised vision of India that minimised the EIC’s violent activities.

The painting was commissioned in 1784 by Warren Hastings shortly before his return to England the following year. Hastings was the first British Governor-General of Bengal, serving from 1773 to 1785. The holders of this post were tantamount to de facto rulers, while the Nawab retained nominal, chiefly ceremonial leadership status. Having established a permanent presence in Awadh, the Company could count the region as its main ally in northern India. Although Hastings does not appear in the painting, he recorded his attendance at the event in his diary. It has been suggested that the other empty space on the sofa, next to the place where the Nawab had been sitting, may register his absence. He was one of several spectators not depicted, a situation which may reflect their concern over British moralistic objections to the perceived decadence of life for EIC employees in India (de Almeida and Gilpin 2017, pp.139–40). William Golding of the EIC’s Corps of Engineers, for instance, was not present at the cockfight, but stood in for someone who refused to sit for the painting.

Asaf-ud-Daula was the grandson of Abul Mansur Mirza Muhammad Muqim Ali Khan (c.1708–1754), better known as Safdar Jang, a key figure in the Mughal court during the final years of the Mughal Empire. Safdar Jang was the second Nawab of Awadh when he succeeded Saadat Ali Khan I in 1739. All future Nawabs of Awadh were his patriarchal descendants. Historian David Olusoga writes that Asaf was ‘a passionate and serious patron of architecture and a genuine connoisseur of poetry and painting’ (Olusoga 2018, p.147). After the Battles of Plassey (1757) and Buxar (1764), the EIC imposed taxes on the Nawab, in return for which the British provided him with a permanent brigade, a temporary brigade and a personal bodyguard. The art historian Griselda Pollock has argued that the figure of the Nawab has not only been misrepresented, but ridiculed, as his ‘artistic connoisseurship and cultural patronage is erased’ by ‘orientalising feminisation’ (Pollock 2003, p.157).

Pollock has argued that in Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match the Indian population is ‘reduced to passive spectatorship, exotic decoration, entertainment, and sex, and positioned as lowly’ (Pollock 2003, p.159). Past texts accompanying the painting at Tate have reinforced this perspective. A caption written in 2004, for example, stated that ‘cockfighting was frowned on as cruel, but in colonial India the “normal” rules of morality did not apply.’ Texts accompanying this painting have also focused on the Nawab’s sexuality and apparent sexual arousal in the painting. A caption from 1997, for instance, ridiculed the Nawab for his rumoured queerness, reproducing speculation that he did not consummate his marriages and that he fathered no children.

A caption written for Tate in 1999 interpreted this painting as depicting a harmonious event where ‘Indians and Europeans mingled on equal terms’ (display caption, 1999). However, scholars have highlighted the veiled power differentials between the European and Indian figures and set out the colonial motivations behind the depiction of harmony in the painting. Art historian Hassan Vawda, for example, has argued that ‘the European presence, in this specific time within India, was embodying a mindset that the orientalist taking part in the “local cultures” is to be celebrated, without reflection on taking control’ (Vawda 2021, accessed 1 August 2022).

The imaging of racial difference in this work is especially apparent when compared to known versions of this scene that were painted by Indian artists. In a version painted by a Lucknow artist in c.1830–5 (British Library, London, shelfmark Add.Or.3118), there is a greater sense of visual equilibrium between the figures of Mordaunt and Asaf, who crouch side-by-side as they engage in the sport. A version of the painting owned by Asaf (often referred to as the ‘Ashwick’ version) was apparently completed by an unknown Indian artist working in Lucknow (Webster 2011, pp.507–9; and Martin Postle (ed.), Johan Zoffany RA: Society Observed, New Haven and London 2011, cat. no.86). This painting is now at White’s Club, London (Smith, Brown and Jacobi 2015, p.164), but was previously thought to have been destroyed during the ‘Indian Mutiny’ of 1857, an effort to achieve independence from Britain (Vawda 2021, accessed 1 August 2022). A version painted by an Indian artist from the Company School, Patna, was sold at Sotheby’s in London in 2014 (‘Art of Imperial India’, 8 October 2014, lot 324).

Tate’s version of the painting is often referred to as the ‘Daylesford’ version. Zoffany described this work as ‘an historical picture … composed of a great number of small figures’ (Webster 2011, p.509). Zoffany was paid 15,000 rupees (about £1,500) for the painting, which was finished after Hastings’s return to England and dispatched to him in February 1788. Contemporaneous prints survive of the Tate/Daylesford version, attesting to the subject’s popularity in Britain, where there was a growing market for ‘exotic’ images of Britain’s colonies. These include an engraving produced by Richard Earlom in 1792 (see, for instance, British Museum, London, accession no.1872,0309.428) and the anonymous 1794 ‘key’ to the painting.

Further reading

Purnendu Basu, Oudh and the East India Company, Lucknow 1943.

Griselda Pollock, ‘Cockfights and Other Parades: Gesture, Difference, and the Staging of Meaning in Three Paintings by Zoffany, Pollock, and Krasner’, Oxford Art Journal, vol.26, no.2, 2003, pp.143–65.

Maya Jasanoff, Edge of Empire: Lives, Culture, and Conquest in the East, 1750–1850, New York 2005.

Natasha Eaton, ‘Critical Cosmopolitanism: Gifting and Collecting Art at Lucknow, 1775–97’, in T.J. Barringer, Geoff Quilley and Douglas Fordham, Art and the British Empire, Manchester and New York 2007, pp.189–204.

Mary Webster, Johan Zoffany, 1733–1810, New Haven and London 2011, pp.497–509.

Alison Smith, David Blayney Brown and Carol Jacobi (eds.), Artist and Empire: Facing Britain’s Imperial Past, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2015, pp.164–5.

Hermione de Almeida and George H. Gilpin, Indian Renaissance: British Romantic Art and the Prospect of India, Aldershot 2017.

David Olusoga, ‘Acts of Empire’, Civilisations: First Contact – The Cult of Progress, London 2018, pp.123–48.

Hassan Vawda, ‘Framing (and Reframing) Zoffany’s Painting, “Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match”’, ArtUK, 24 May 2021, https://artuk.org/discover/stories/framing-and-reframing-zoffanys-painting-colonel-mordaunts-cock-match, accessed 1 August 2022.