What do Jane Austen, the French Revolution and a hung-over docent have to do with Warren Hastings? Not surprisingly, you haven’t asked…

“George Clive and his Family with an Indian Maid”, c.1763–5, by Joshua Reynolds, now re-identified as “Tysoe Saul Hancock, his wife Philadelphia, their daughter Elizabeth and their Indian maid Clarinda” | Gemäldegalerie in Berlin

THE OPPRESSIVELY LONG BACKGROUND

Jane Austen’s father was nine and his sister Philadelphia 10 when they were left impoverished orphans in 1740.

George Austen was taken up by his wealthy uncle Francis Austen, a successful lawyer at Tunbridge who supported him liberally throughout his early life, including the obtaining of a fellowship, at St. John’s College, Oxford and eventually purchasing the living of Deane in Hampshire. The living of the adjoining living of Steventon rectory (where Jane Austen was born) was given by his cousin Mr. Knight.

Things looked good for George – and Jane Austen.

Not so good for poor Philadelphia. By the age of 15 she was miserably apprenticed to a milliner and was still ‘on the shelf’ at the ripe old age of 21. In 1752, she was shipped off to India as part of the Fishing Fleet – in the hopes of finding a husband.

Since the late 17th century, the East India Company had shipped women out to India to become brides for its officers. With a huge disproportion of men to available women, even the plainest girl could find a mate.

While onboard the Bombay Castle, she made friends with the future Lady Clive, Margaret Maskelyne, landing in Madras August 1752. The ‘Fishing Fleet’ objectives were promptly met for both women and they married within 6 months of arrival: Philadelphia to Tysoe Saul Hancock, a surgeon employed by the Company at Fort St David; Margaret to Robert Clive, swiftly climbing the ranks of the EIC thanks to his recent ‘success’ in the Siege of Arcot.

In 1759, with support from Clive, Hancock secured a post as surgeon in the north at Fort William, Calcutta. Philadelphia traveled in advance and took up residence with the Clives for several months. The Hancocks remained in Calcutta when the Clives sailed home in February 1760, with £300,000 and a rather questionable humanitarian reputation.

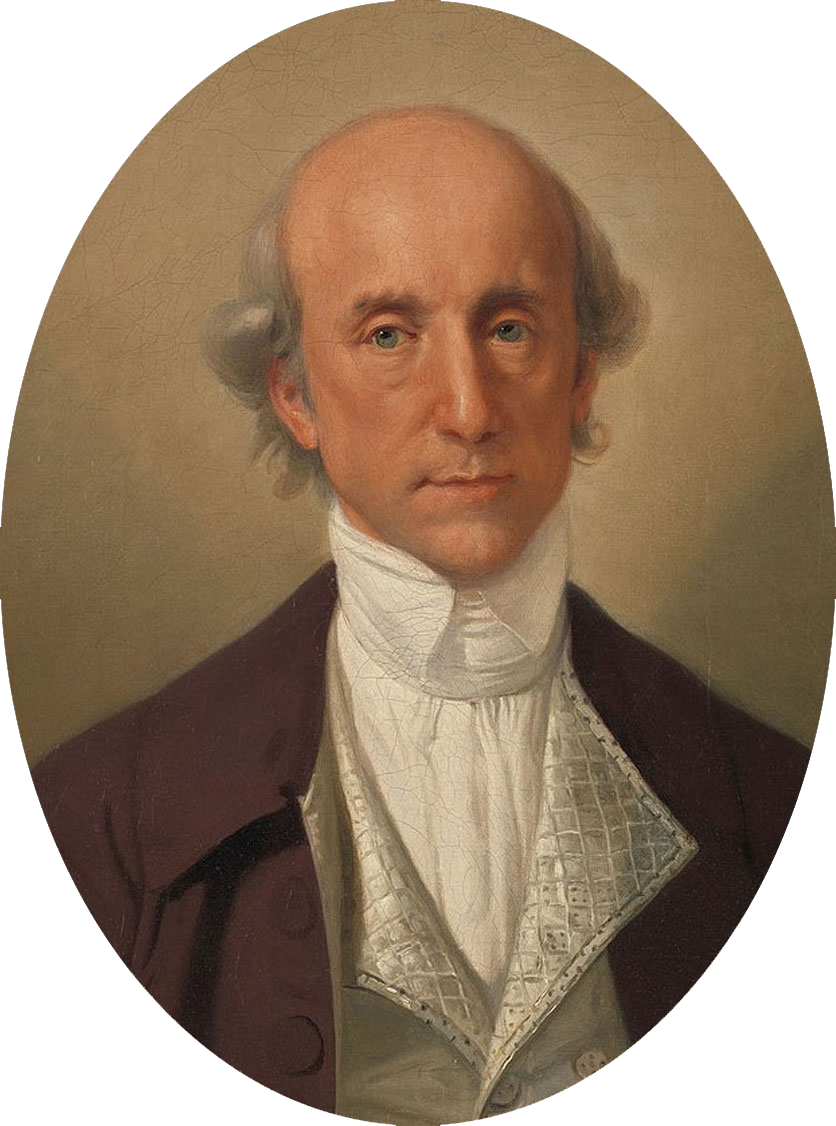

In Calcutta, the Hancocks formed a friendship with Warren Hastings, even setting up various business ventures together. Later the first Governor General of Bengal, Hastings was at this time a prominent administrator with the East India Company – busy laying the foundation for British power in India. Unlike Clive, however, Hastings appeared to respect and have an interest in the culture and way of life of this colonized country.

Hastings had married a widow in 1757 who bore him two children: a son named George and a daughter who died in infancy followed some months later by her mother in 1759.

George Austen reappears in this saga, when in 1761, at Philadelphia’s suggestion, Warren Hastings ships his young son George home to the care of George Austen – at this time a bachelor. A bit of controversy surrounds this bit of the story, as some Austen historians find it ‘very doubtful’ that Hastings would have sent his young son to England to the care of a bachelor still taking orders and not yet in possession of a living. George Austen marries Cassandra Austen in 1764 and would then have had a home to accommodate young George Hastings but of course that is a few years later. There are Austen family memories, however, of the young bride Mrs. Austen deeply upset at the boy’s death in the autumn of 1764. Though the meticulous Steventon church registry has no record of the death, the boy may have died and been buried elsewhere.

Whatever the case, the child died. There is some evidence that Hastings remained grateful to the Austens for looking after his son.

LE SCANDAL (OR NOT)

Meanwhile in India, after 8 years of childless marriage, Philadelphia became pregnant and in 1761, a daughter was born: Elizabeth, to be known as first Bessy and later, Eliza. Hastings was made her godfather.

Herein lies the rub, a scandal not corroborated by historical evidence but certainly by rumor, speculation and a soupçon of sexism – as usual. Immediately whispers began to spread about a possible affair between Philadelphia and Hastings.

The belief that Eliza was indeed the daughter of Hastings was also supported by that most obvious of marriage metonymies – dissatisfaction with her husband. Margaret Clive, now Lady Clive, describes him as ‘vastly fat but unhealthy.’ Years later, Jane herself weighs in on this possibly bleak union,

“She had been… unhappily married…united to a man of double her own age, whose disposition was not amiable, and whose manners were unpleasing, though his character was respectable.”

In November of 1761, Lady Clive received a letter from her gossipy friend Major John Carnac ,

“Would You believe it, Madam, Mrs. Hancock is pregnant. The scandalous chronicle gives the credit thereof to Hastings…”.

While many at the time believed this to be true, Tysoe Saul Hancock seems to have remained on the best of terms with both his wife and Hastings and in January 1765, the Hancock family, together with Warren Hastings, set sail for England on the Medway arriving in London June 1765.

Writing in May of 1766, Lady Clive, if not entirely convinced of the propriety of the situation, remained loyal to Philadelphia Hancock,

“I am concerned to see a particular paragraph in your & Lord Clive’s letter, I mean that which relates to an acquaintance of mine, now in England. Her outward deportment is so strictly proper, that I hope if anything has been amiss, she has only the punishment of remembering it, I mean that nobody here thinks any harm of her… . She is going to retire into the country with her husband, & one of the prettiest sensible children in the world… . My Lord’s injunctions are so positive not to keep up the acquaintance, that I shall not seek for occasions of meeting… .Her husband is prodigiously fat, but in a very bad way I think.”

Soon after this letter was written, Lord Clive insisted the friendship be dissolved.

Following a few years of the high life in London, including being painted by Reynolds, Tysoe Saul Hancock determined he must return to India for more dosh, with Philadelphia and Eliza remaining behind. The correspondence between Hancock and his wife, while affectionate, would never set the Thames on fire. There was one odd exchange, however.

Hastings never officially acknowledged paternity but stayed closely in touch with the Hancocks, advising on Eliza’s education and providing for her upkeep. In addition, he famously set up a trust of £5,000 that was later increased to £10,000 for the girl. The interest derived from the trust was to be paid to Philadelphia and Hancock while they were alive, but once they died, the balance would go to Eliza.

When Eliza was 10 years old, her mother told her that her godfather had left her a fortune. Mr Hancock wrote and warned his wife not to talk to anyone about it.

“Let me caution you not to acquaint even the dearest friend you have with this circumstance. Tell Betsy only that her godfather has made her a great present, but not the particulars.”

Hancock died in India in 1774, leaving Philadelphia’s income greatly reduced compelling her to go and live on the Continent with Eliza. They stayed in touch with Hastings, who was becoming more influential in India.

In a letter, Hastings affectionately writes to Philadelphia,

“My dear and ever-valued friend…Kiss my dear Bessy for me, and assure her of my tenderest affection. May the God of goodness bless you both!”.

Obviously, Hasting’s interest in the welfare of the Hancock women, mother and daughter, remained strong.

LIBERTÉ, ÉGALITÉ, FRATERNITÉ, or something to that effect

Settled in France by 1779, Eliza darts and flits about pre-revolutionary France with some success. At the age of 20 she marries “one of the most beautiful men of his time”, a wealthy French Army Captain, Jean-François Capot de Feuillide, from the province of Armagnac. Eliza thus became Comtesse de Feuillide.

Their story begins well-enough. In 1782, King Louis XVI concedes them the great Marshes of Barbotan and Gabarret, an immense territory of five thousand arpents (about an acre) with the responsibility of draining and developing the land. Part of Eliza’s dowry could have been used to finance improvement works and build smallholdings, as at his death Jean-François had a vast deal of debt – impossible to raise for a simple captain.

In 1786, a very pregnant Eliza set out for England to visit the Austen’s but did not make it past Calais before giving birth to a boy, Hastings de Feuillide, who was thought to have learning difficulties.

At the first rumblings of the Revolution in 1790, Eliza, her husband (who was loyal to the French monarchy), their child and Philadelphia left for England but he felt forced to return to France to avoid being dispossessed of his property as an emigrant.

It was also during this time that the first signs of Philadelphia’s breast cancer appeared. She never recovered and began a slow march towards death. Eliza contacted her husband and the Count arrived in England around late February just in time for Philadelphia to pass away on Sunday, 26 February. She was buried in the churchyard of St John-at-Hampstead, London. Her tombstone was inscribed with the following:

“In memory of Philadelphia Wife of Tysoe Saul Hancock whose moral excellence united the practice of every Christian virtue she bore with pious resignation the severest trials of a tedious and painful malady and expired on the 26th day of February 1792 aged 61.”

In 1794, Feuillide finds himself accused of having helped the Marquise de Marbeuf to hide food intended for the Austro-Prussian army. Condemned to death by the Revolutionary Court of Paris, he is guillotined in 1794.

MEANWHILE IN INDIA…

Hastings was to leave India in 1784 not under a cloud but rather a monsoon. As the first Governor General of India, Hastings oversaw a period of great expansion of British rule both administratively and geographically.

It was also a period of great tragedy. What the British described as “farming” the Bengali peasants (ryots), but was actually over-taxing of Bengalis meant that 10 million Bengalis perished in the Great Bengal Famine of 1769-1770.

To his credit, according to William Dalrymple:

He got quickly to work, beginning the process of turning the EIC into an administrative service. Hastings first major change was to move all of all the functions of government from Murshidabad to Calcutta…. Throughout 1773, Hastings worked with extraordinary energy. He unified currency systems, ordered the codification of Hindu laws and digests of Muslim law books, reformed the tax and customs system, fixed land revenue and stopped the worst oppression being carried out on behalf of private traders by the local agents. He created an efficient postal service, back a proper cartographic survey of India by James Rennell and built a series of public granaries, including the great Gola at Patna, to make sure the famine of 1770-71 was never repeated…. Underlying all Hastings’ work was a deep respect for the land he had lived in since his teens…. Hastings genuinely liked India, and by the time he became Governor spoke not only good Bengali and Urdu but also fluent court and literary Persian.

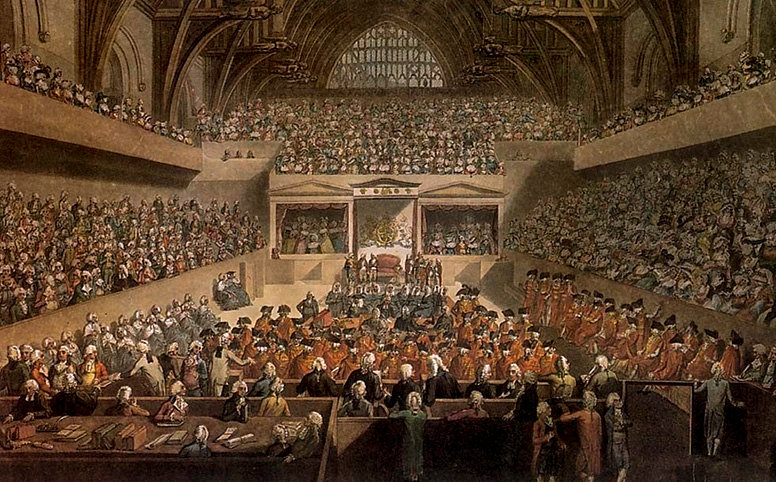

When he returned to England, he was charged with high crimes and misdemeanors by Edmund Burke (and Sir Philip Francis whom he had wounded in a duel in India).

He was impeached in 1787 but the trial, which began in 1788, ended with his acquittal in 1795. Hastings spent most of his fortune on his defense, although the East India Company did contribute towards the end of the trial.

ALL’S WELL?

Eliza went on to marry her cousin, Henry Austen (Jane’s brother), who also corresponded with Hastings.

It has also been assumed that she persuaded Henry to go into banking, although she did not live to see this venture become a complete failure. Hastings died in 1801 from what is speculated to have been epilepsy. Twelve years later, 25 April 1813, Eliza died after suffering a long illness. It is known that Jane visited Sloane Street (Eliza and Henry’s home) regularly and helped to nurse her during her final years. Eliza is buried with her mother and son in a cemetery in Hampstead, North London.

JA’s brother Henry wrote to congratulate Hastings on his acquittal for impeachment in 1795,

“Among the earliest lessons of my infancy I was taught by precept and example to love and venerate your name. I cannot remember the time when I did not associate with your character the idea of everything great, durable and good.”

Hastings also used his influence with the Admiralty in Frank Austen’s favor in 1794.

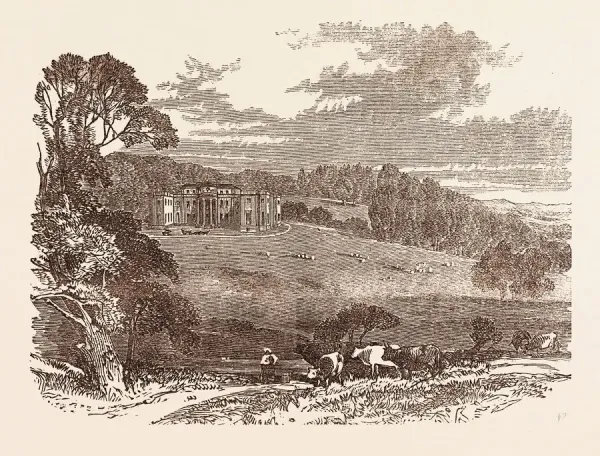

In 1788 Hastings bought an estate at Daylesford, Gloucestershire, including the site of the Hastings family’s medieval seat for £54,000. Thereafter he remodelled the house to designs by Samuel Pepys Cockerell with classical and Indian decoration and gardens landscaped by John Davenport. In 1801 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In 1816, he rebuilt the Norman church, where he was buried two years later.

Eliza and Henry were regular visitors to Daylesford, but Eliza’s first visit was made in August 1797, a few months before her second marriage. From Cheltenham she wrote,

“One of my principal inducements for coming here was the neighborhood of my old friends the hasting’s whom I am just returned from visiting. They have got a place called Daylesford, which is one of the most beautiful I ever saw. I will not wrong it by endeavoring to give a description of it, and it shall therefore suffice to say that the park and grounds are a little paradise, and that the house is fitted up with a degree of taste and magnificence seldom to be met with”.

When Pride and Prejudice was published, Hastings wrote about it admiringly. Jane was delighted and wrote to Cassandra,

“I long to have you hear Mr H.’s opinion of P. & P. His admiring my Elizabeth so much is particularly welcome to me.”

A TIPPLE TOO FAR…

On the subject of a young docent who found herself ‘in bits’ during a Jane Austen lecture

Our first foray into Bath about 15 years ago was of course precipitated by a visit to the Jane Austen Centre. And there we went, very early the day after our arrival, our heads full of jet lag fluff. The doors opened at 9 am but at 8:30 we had to join a queue – a buzzy, lively queue representing many nationalities.

We were escorted and packed tightly into a smallish room with a podium at one end. Our lecturer was a young woman, rumpled in appearance who twisted herself into a chair instead of standing. It started well, as all lectures with such an enthusiastic audience full of admirers would. I’m sure she wasn’t doling out any new information to anyone but we were polite.

After only 5 minutes she excused herself and ran from the room into the office next door. Regrettably, we could all hear her retching with gusto into hopefully some sort of receptacle, or at the very least a drawer? A few more seconds of coughing and gagging brought her before us again and her still polite, eager audience was willing to overlook a great deal. She resumed her lecture with no chagrin or embarrassment – which should have forewarned us. Too ill to last another 5 minutes, she left the room again not to return.

A flustered older woman shuffled in, opened a side door with steps leading down to a dark basement, herded us downstairs to a long narrow room promoting the latest P&P movie and then closed the door behind us. Ominously, we all heard her lock the door. And so here we found ourselves at the celebrated Jane Austen Centre, locked in a room filled with life-size cardboard cutouts of Keira Knightly. Our most likely friend now was a pub that opened early.

But a rich amends was preparing for us…

A few days later, during a long country walk, we found ourselves fording a stream in the village of Adlestrop and taking shelter in the tiny church of St Mary Magdalene. Unbeknownst to us, we were walking into a Jane Austen shrine of sorts. On this cold, grizzly December day (a few days after Jane’s 230th birthday), we found ourselves in a dark, narrow, lofty nave with no side aisles leading to what looked like a medieval stone arch. On either side were 18thc monuments to something or other. High above us were ornate wooden roof beams.

What little light there was came from maybe 18c window additions. Obviously many centuries of well-meaning parishioners had had their over-exuberant hands all over this. On the right-hand side by the door was a little photocopy of the famous portrait of Jane Austen at the NPG with a description of her time in Adlestrop below. And so here we found ourselves, alone in a dark, quiet, frosty church sitting in the very pews where she once sat…

And apparently was inspired by.

Jane Austen, who made three recorded (and probably other) visits there in the 1790s and 1800s to see her mother’s cousins Thomas, Mary and Elizabeth Leigh at the rectory and her second cousin James Henry Leigh at the “big house”, Adlestrop Park.

The village is still centered on these two properties, with the church, manor farm and a string of cottages along the main street making up the rest. The river Evenlode runs near the western side of the village and the village is pleasantly situated on the slope of a hill fronting the southwest.

Warren Hasting’s house is less than a mile from Adlestrop and Jane would have certainly visited him with her mother when staying in Adlestrop.

The improvements that took place at both Adlestrop Park and Stoneleigh Abbey at the turn of the century under the direction of Humphrey Repton, the most fashionable landscape architect of the day, fed directly into the Sotherton episodes in Mansfield Park (and Repton is one of very few real-life characters to be mentioned in Austen’s fiction), and Huxley points out how each of Austen’s novels has some reference to “Improvement”: the management of estates and the relation between landscapes and purse-strings. It is at this subcutaneous level that the importance to Jane Austen of places like Adlestrop becomes most interesting.

The Adlestrop Leighs were also quick to exploit the opportunities that Enclosure Acts offered. Thomas Leigh, rector of the village for fifty years, enclosed the green and diverted a road for his own benefit, while James Henry grabbed a bit of the churchyard to add to the Park’s pleasure grounds.

Jane Austen had a ringside view of all these changes on her visits in 1794, 1799 and 1806, though she is unlikely to have approved of them much. Her taste was more for untouched backwaters such as Thornton Lacey in Mansfield Park.

“I was suddenly, upon turning the corner of a steepish downy field, in the midst of a retired little village between gently rising hills; a small stream before me to be forded, a church standing on a sort of knoll to my right— which church was strikingly large and handsome for the place, and not a gentleman or half a gentleman’s house to be seen excepting one—to be presumed the Parsonage— within a stone’s throw of the said knoll and church. I found myself, in short, in Thornton Lacey.