The Benin Bronzes

The Benin Bronzes | British Museum

The Benin Bronzes are a collection of over 5,000 artifacts, primarily brass and bronze sculptures, that were created in the former Kingdom of Benin, located in present-day Nigeria, between the 13th and 16th centuries. These artworks, looted by British forces in 1897, are now the subject of repatriation efforts. They offer insights into the history, culture, and power structures of the Benin Kingdom.

The bronzes provide a detailed record of the Benin Kingdom, its dynastic history, social structure, and interactions with neighboring regions.

The artifacts were taken during the British Punitive Expedition of 1897, which resulted in the destruction of Benin City. The bronzes are now the subject of repatriation claims by Nigeria, with some already returned by countries like the Netherlands.

First and foremost is the fact that exquisitely manufactured objects such as the Benin Bronzes were not made for the masses, the people. They were commissioned by wealthy elites to serve as exclusive emblems of political power and social status. This lent substance to the monarch’s jealously guarded right to rule over his or her subjects, whose labour and taxes would be funnelled into grand palaces and lavish works of art that the masses themselves would never get to see or enjoy.

The Benin Bronzes, much like the extravagant collection of Chinese bronzes, porcelains and paintings stored in the Forbidden City, were not originally regarded as symbols of any nation, nor did they tell that nation’s ‘story’.

If they told any story at all, it was one that extolled the character, taste and rule of the haughty kings and emperors who jealously hoarded them – and of the gods who supposedly blessed them.

Western reactions to Benin Bronzes

Civilisations – BBC

Returning the Benin Bronzes

Cambridge University

How Europe Stole Africa’s

Greatest Treasures

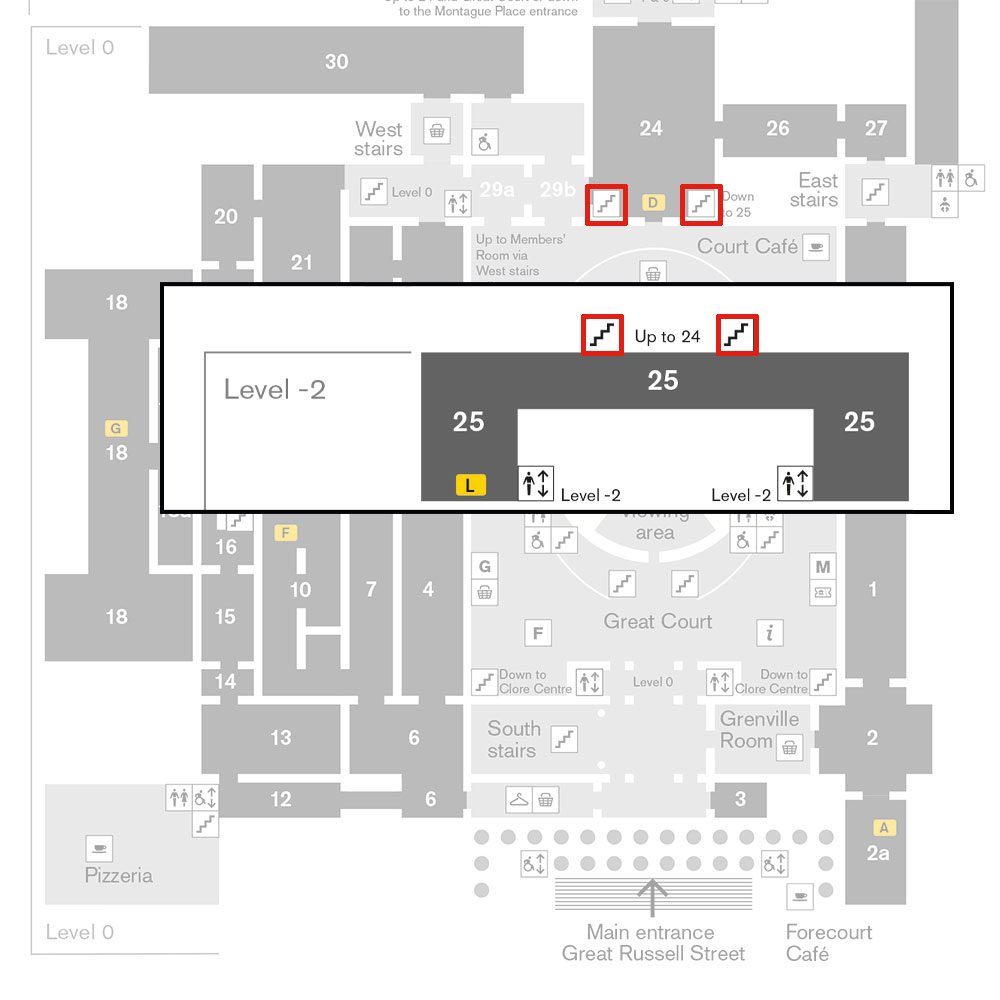

How did the objects come to the British Museum?

By the end of the 1800s, the Nigerian coast and its trade were largely dominated by the British. It is in the context of this aggressive expansion of colonial power that the Benin Bronzes came to the British Museum.

During the second half of the 1800s, the balance of power between West African kingdoms such as Benin, and the European nations they traded with, shifted towards European control. In the late 1800s, industrialised European nations supported by new military technologies began to exert greater power across the African continent. This political and commercial movement developed into the territorial land-grab known as the ‘Scramble for Africa’.

This period of West African history was also significantly shaped by the devastating effects of the transatlantic slave trade. This vast traffic in enslaved people supplied labour to the plantations in the Americas, including British-controlled colonies. African kingdoms including the Benin Kingdom, played a role in capturing and selling enslaved people to feed this European-led trade although the precise nature and extent of this exploitation remains debated. While by the late 1800s this trade had been largely abolished, its increasing scale and barbarity in the preceding centuries had a massive impact on the economic potential of West African societies.

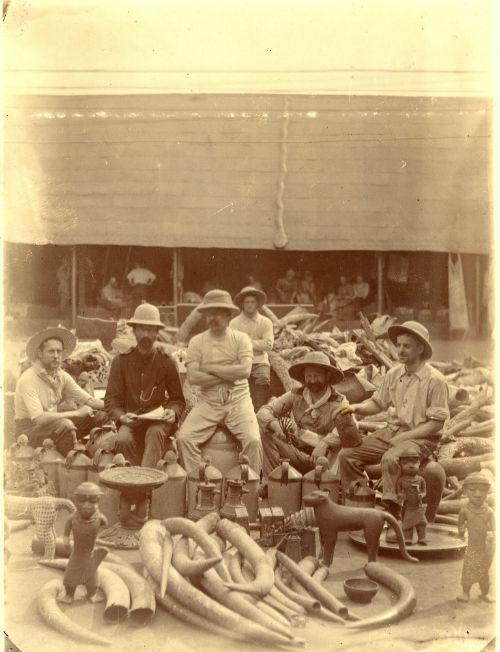

The desire to further extend British power and influence in the region ultimately led to a clash with the Kingdom of Benin. The gradual expansion by the British into territory neighbouring the kingdom and an increasing reluctance to accept Benin’s trading conditions created an atmosphere of distrust and animosity. In January 1897 an allegedly peaceful but clearly provocative British trade mission was attacked on its way to Benin City, leading to the deaths of seven British delegates and 230 of the mission’s African carriers. This incident triggered the launch of a large-scale retaliatory military expedition by the British against the Kingdom of Benin. In February 1897 Benin City was captured by British forces.

Benin suffered a bloody and devastating occupation. No exact figure can be given for the number of Benin’s population who were killed in the conquest of the city. However, oral and written accounts suggest that there were many casualties during the sustained fighting. The occupation of Benin City saw widespread destruction and pillage by British forces. Along with other buildings, the Oba’s palace was burned and partly destroyed. Its shrines and associated compounds were looted by British forces, and thousands of objects of ceremonial and ritual value were taken to the UK as official ‘spoils of war’ or distributed among members of the expedition according to their rank. These included objects removed from royal ancestral shrines, among which were commemorative brass heads of former Obas and associated carved ivory tusks. The looted objects also included more than 900 brass relief plaques, probably dating between 1500–mid-1600s, found in a storage room within the palace. Having previously decorated pillars in the palace compounds, many of these plaques present a vivid depiction of Benin court life and ritual, while others record important trade relationships or commemorate successful military campaigns. Following the occupation, the Oba was captured and sent into exile, while several Benin chiefs were executed. Justified as legitimate military action against a ‘barbarous’ kingdom, this brutal colonial episode effectively marked the end of the independent Kingdom of Benin. Following the interregnum of 1897–1914 a new Oba, Eweka II, was installed. Despite subsequent administrative and political upheavals many of Benin’s customs, rituals and titles have survived and thrive today.

In the autumn of 1897, the British Museum displayed 304 Benin plaques on loan from the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and subsequently petitioned successfully to receive 203 of these as a donation. Most of the remaining plaques were sold to UK and German museums and to private dealers, while a few were retained by the Foreign Office. Other early collections were purchased or donated to the Museum by members of the Benin expedition.

The British Museum collection only grew to its current size following the acquisition of major private collections, such as that of Harry Beasley in 1944, William Oldman in 1949 and Sir Henry Wellcome in 1954. In 1950 and 1951 the Museum deaccessioned 29 of the Benin plaques in the collection. At the time these objects were understood as ‘duplicates’ of other plaques retained in the collection, something which further research has shown to be incorrect. Some of these were subsequently sold, exchanged or donated to the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria (25 in number). These plaques were later accessioned into the collections of newly established museums in Lagos and Benin City. In 1954 one plaque was sold to the colonial government of the Gold Coast and was later incorporated into the collections of the National Museum in Accra. A further eight plaques were sold to or exchanged with private dealers and collectors between 1952 and 1972.

In addition to objects that can be traced directly to the 1897 expedition, the Museum cares for objects from or associated with Benin City that sit outside the context of the expedition, including brass castings, carved ivories, contemporary artworks, textiles, casts and replicas, and archaeological finds.

What has been requested?

In October 2021 the British Museum received a written request for the return of ‘Nigerian antiquities’ from the Federal Ministry of Information and Culture, Nigeria.

In addition, representatives of the Benin Royal Palace have made various public statements asking for the Benin collections to be returned, most recently at the Benin Dialogue Group meeting hosted by the Museum in October 2021.

These requests are framed within the context of longstanding dialogues with the Museum, including during the visit of the then Director of the British Museum to the Benin Royal Court in August 2018.

Status of discussions

The Museum has positive relationships with the Royal Palace in Benin City and with the National Commission for Museums and Monuments, Nigeria (NCMM).

The Museum’s then Director, Hartwig Fischer, visited Nigeria in August 2018. He met with senior Museum colleagues in Lagos and Benin City and had an audience with His Royal Majesty Oba Ewuare II which included discussion of new opportunities for sharing and displaying objects from the Kingdom of Benin. During that visit His Royal Majesty Oba Ewuare II repeated his request for Benin collections to be returned. He also acknowledged, however, that the objects serve as ‘cultural ambassadors’ for Benin culture when displayed internationally.

Following the written request in October 2021 for the repatriation of Nigerian antiquities from the Ministry of Information and Culture, the Museum asked for some points of clarification. In July 2022 Nigeria’s then Minister of Information and Culture, Lai Mohammed, visited the Museum and was welcomed by staff in the Department of Africa, Oceania and the Americas. He was able to provide the necessary clarifications in a friendly and courteous meeting. Since this visit there have been significant changes at a federal level in Nigeria with the election of a new President in May 2023 and the appointment of a different Minister of Information and Culture. The Museum remains open to discussion with partners in Nigeria.

From, ‘Plunder?’, Justin M. Jacobs & The British Museum