TATE BRITAIN | MAP

Explore 500 years of British art and its many stories and voices. Founded by the nation (and funded largely by Sir Henry Tate) in 1897, it houses a substantial collection of the art of the United Kingdom since Tudor times, and in particular has large holdings of the works of J. M. W. Turner, who bequeathed 180 oil paintings, and about 19,000 drawings and watercolors to the nation but stipulated that a gallery should be built by the National Gallery within five years to house them. (Unfortunately, John Ruskin, of the the seven executors of Turner’s will, destroyed a large collection of what he considered to be ‘erotic’ works – characteristically or uncharacteristically, depending on how you view Ruskin…)

Sir Henry Tate was a sugar baron and popularizer of the sugar cube – you can still see his name today on sugar packets. He, too, wished to donate his collection of modern British art which was valued at £75,000 (equivalent of approximately £6.1 million today) and helped to finance the building to house it. A gorgeous museum was built directly on the Thames, the site of the former Millbank Prison. (The name ‘Millbank’ is from the mill for Westminster Abbey, which is to the east of the gallery.)

Unless there is a blockbuster exhibition on, Tate Britain is never that crowded. There is fabulous Tate-to-Tate boat available, if you wish to visit The Tate Modern as well.

The Cholmondeley Ladies, c.1600–10

Unknown Artist | Exiles and Dynasties: 1545–1640

According to an inscription in gold lettering to the bottom left of the painting, it shows “Two Ladies of the Cholmondeley Family, Who were born the same day, Married the same day, And brought to Bed the same day.”

At first sight, the two women and their two babies appear almost identical, each mother wearing similarly elaborate clothing decorated with lace and jewelry, each baby swaddled in a christening robe and held at a similar angle. On closer inspection, numerous details of the clothing, jewelry, and facial characteristics of the two pairs are seen to differ. The pose is not known to have been used in any other British painting, but was frequently seen in contemporary funerary art.

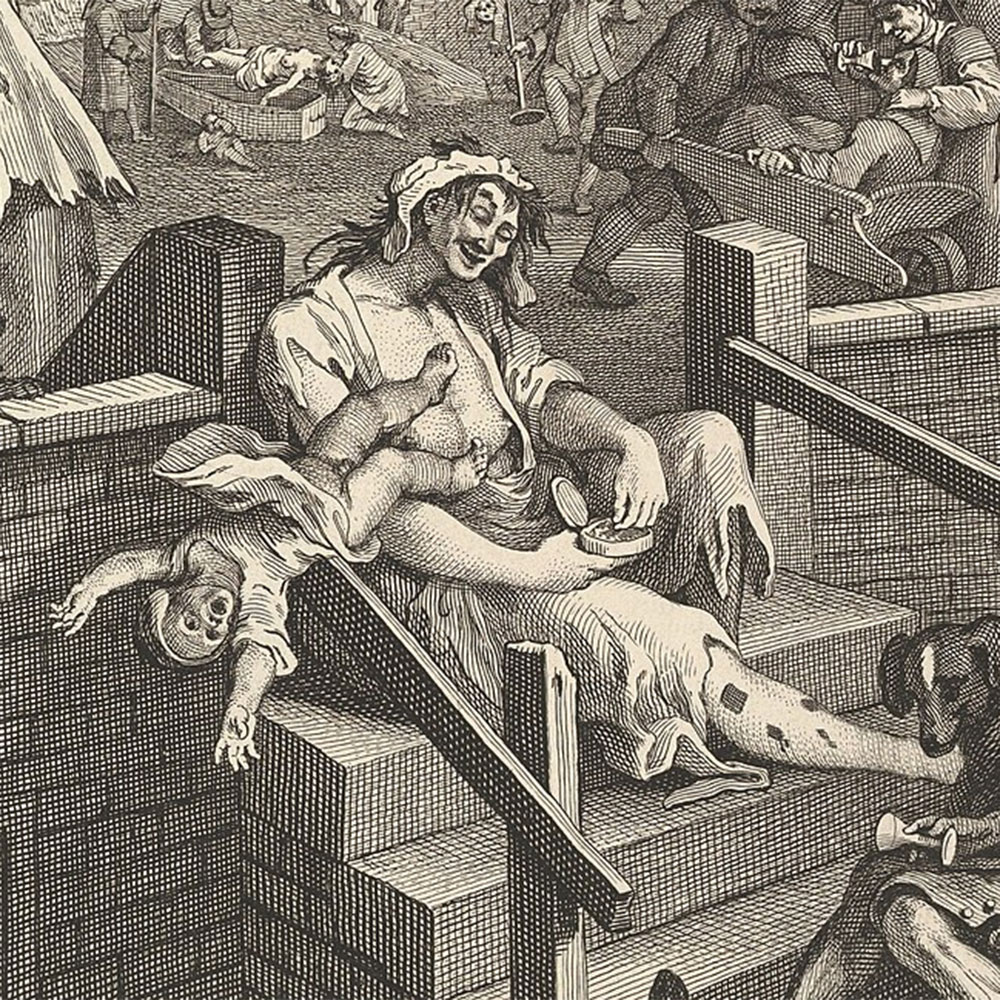

Gin Lane, 1751

William Hogarth | Metropolis: 1720–1760

In 1723 the death rate in London outstripped the birth rate and it remained higher for the next decade with as many as 75% of babies dying before they reached the age of five. One of the causes was the Gin Craze, the Opioid Crisis of the day. The production of cheap gin was the scourge of London’s poorer districts in the early eighteenth-century. Unregulated and highly potent, the gin was often mixed with dangerous substances.

William Hogarth’s print shows its destructive effects. It was produced in support of the Gin Act (1751) which sought to control gin production and consumption. His social consciousness was almost manifest in his support of the new Foundling Hospital, where mothers could leave their young children ‘no questions asked’.

The following paintings are all found in the ‘Troubled Glamour: 1760–1830’ Gallery. None are necessarily masterpieces but I wanted to mention them in terms of the historical context – slavery and empire, a subject too-long ignored in the art world. Now, thankfully, including these simultaneous histories when describing artwork is becoming more usual. It can affect the way you view the artwork now and alter the understanding of young people for the future.

Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match, c.1784–6

Johan Zoffany | Troubled Glamour: 1760–1830

Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match c.1784–6 is a large oil painting by German-born artist Johan Zoffany. The cockfight represented in the foreground of the painting was based on an event held at the court of Asaf-ud-Daula, the Nawab Wazir (governor) of Awadh (Oudh) in Lucknow on 5 April 1784. The match was between Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula and Colonel John Mordaunt, an employee of the British East India Company (EIC).

Why is this painting controversial? READ MORE

LEARN ABOUT JANE AUSTEN’S CONNECTION TO INDIA

The Baillie Family, c.1784

Thomas Gainsborough | Troubled Glamour: 1760–1830

This imposing portrait reflects Thomas Gainsborough’s artistic ambitions and the social aspirations of the sitters. James Baillie and his family present an elegant, affluent image of domestic harmony. This was underpinned by the wealth Baillie amassed through Atlantic trade and plantations in Grenada and British Guiana, laboured by enslaved people. At his death, he left his son Alexander (in blue), the Grenada sugar plantation, and each child £10,000 – worth about £1.1 million today. Some of the children later claimed compensation following the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

LEARN ABOUT JANE AUSTEN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY

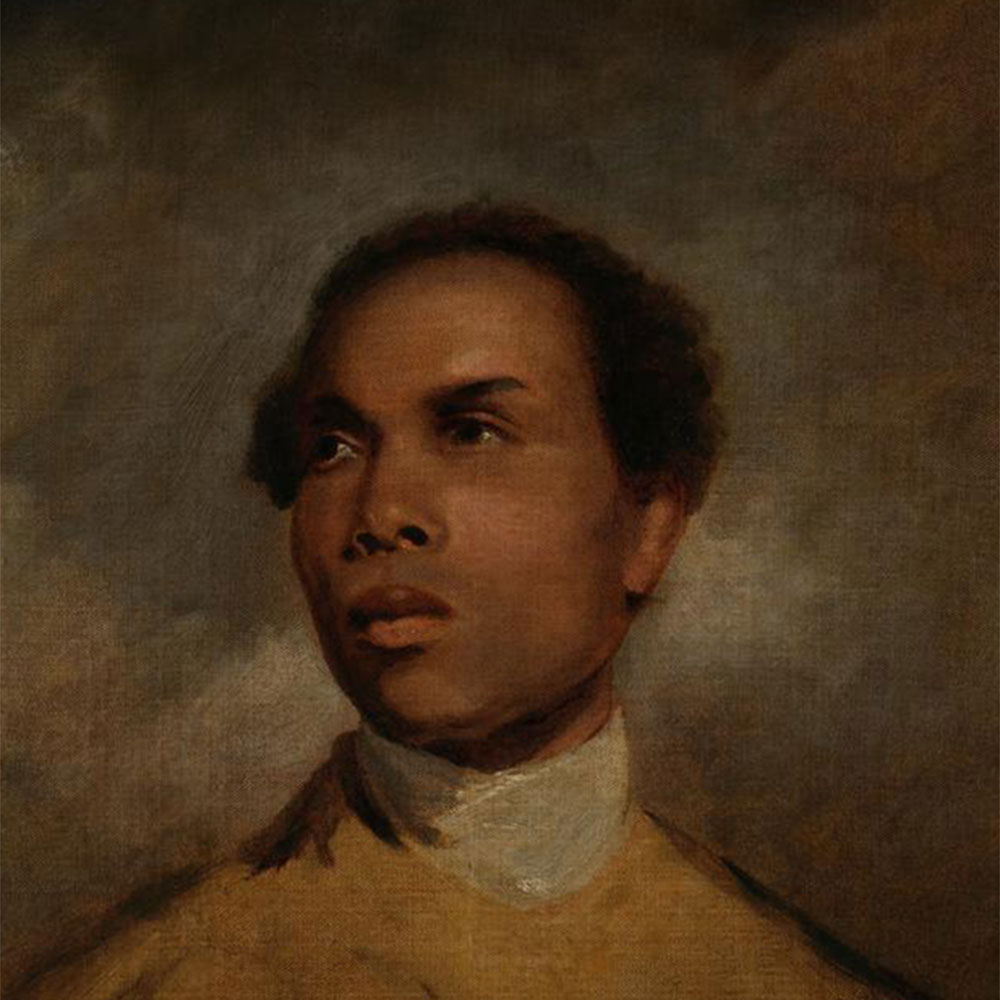

Portrait of a Man, probably Francis Barber, Date Unknown

Sir Joshua Reynolds | Troubled Glamour: 1760–1830

This is a copy of an unfinished portrait by Joshua Reynolds. While not firmly identified, the sitter is understood to be Francis Barber (c.1742–1801). Barber was enslaved at birth in Jamaica by Colonel Richard Bathurst. He took him to England, where Barber was later freed. Barber spent many years assisting the writer Samuel Johnson (1709–1784), becoming Johnson’s heir and a public figure himself. While Barber’s contemplative gaze conveys his dignity, the many versions of this portrait may suggest that, as a Black man, he was treated as an artistic subject rather than as an individual.

A Family Group in a Landscape, c.1775

Francis Wheatley | Troubled Glamour: 1760–1830

Very little is known about the family represented here. The picture gives the impression that they are unposed, spending time together outdoors. Their careful arrangement, however, conveys a sense of hierarchy. At the edge, is a young Black boy. While visually linked by the kite winder he holds and his red clothes, he is physically detached and shown in shadow. These elements may reflect the marginalized position of free and enslaved African domestic servants in Britain during the 18th century. Here, his inclusion is likely intended to signify the wealth and status of the family.

Colonel Blair with his Family and an Indian Child, 1786

Johan Zoffany | Troubled Glamour: 1760–1830

Colonel Blair served in the Bengal army in colonial India. He sits in the centre of this painting in a lavish interior setting alongside his wife and daughters. On the right, a young Indian girl holds a cat. Her identity and relationship to the family remains unknown. It is possible she is an ayah (a housemaid), or perhaps Blair’s child. The child is positioned as an outsider welcomed into the group, echoing colonial sentiment in the British Empire. The paintings on the wall intentionally portray Indian customs as both captivating and outside British ideas of civilization. READ MORE

The Field of Waterloo, 1818

J.M.W. Turner | Revolution and Reform: 1776–1833

The dramatic lighting in this picture highlights the dead bodies piled below. JMW Turner shows the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo (1815), which ended more than a decade of conflict between Britain and France. He had visited the site in 1817, making numerous sketches. Turner emphasizes war’s tragic consequences for all victims, regardless of their nationality or rank. Pictures of battles were expected to be patriotic, but Turner shows ‘friend, foe, in one red burial blent’. This quote from Lord Byron’s poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage was displayed alongside the painting when it was first exhibited.

It is difficult not to empathize with the poor women looking for any sign of life, looking for their loved ones. Though, some critics believe them to be looters. The prospect of thousands of British, French and Prussian teeth – sitting in the mouths of recently-killed soldiers on the battlefield at Waterloo – was an attractive one.

War. The Exile and the Rock Limpet, 1842

J.M.W. Turner | Turner and his Critics

This is my favorite painting in the Tate, which was certainly not the case for contemporary reviews. The press was universal in its condemnation of this picture and the figure of Napoleon was particularly criticized. ‘He is in black military boots’, wrote the Literary Gazette, ‘the continuous reflection of which from his toes in the water give him the appearance of being erected upon two long black stilts, and the whole thing is… truly ludicrous.’ The Athenaeum declared, “In the midst of a canvas smeared with every shade of rose color, crimson, vermillion, and orange, is set up a thing—man it assuredly is not.”

On the other hand, Ruskin, who seems to have valued this picture very highly, commented ‘The lines which Turner gave with this picture are very important, being the only verbal expression of that association in his mind of sunset colour with blood…the conceit of Napoleon’s seeing a resemblance in the limpet’s shell to a tent… (but) that even this poor wave-washed (limpet) had more power and liberty” than the deposed, defeated emperor.

Why do I love this painting so much? I feel it transcends time and space. Not only is it terribly modern, it speaks a universal truth: the transience of power and the inevitability of decline.

Christ in the House of His Parents, 1849–50

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt | Beauty as Protest: 1845–1905

This is Millais’s first important religious subject, showing a scene from the boyhood of Christ. When it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1850. The public reaction to the picture was one of horror and Millais was viciously attacked by the press. Charles Dickens, offended by Millais’ departure from the traditional idealized depictions of the Holy Family, accused Millais of portraying Mary as an alcoholic who looks “so hideous in her ugliness that … she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest gin-shop in England” and thought Jesus a “wry-necked, blubbering red-headed boy in a bed-gown, who appears to have received a poke … playing in an adjacent gutter”.

The effect of the critical comments was to make the Pre-Raphaelite movement famous and to create a debate about the relationship between modernity, realism and medievalism in the arts. The critic John Ruskin supported Millais in a letter to the press and in his lecture “Pre-Raphaelitism” despite personally disliking the painting – changing the world of art forever.

Ophelia, 1851-2

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt | Beauty as Protest: 1845–1905

This work shows the death of Ophelia, a scene from Shakespeare’s play Hamlet. Traumatized when Hamlet breaks off their betrothal and accidentally kills her father, she allows herself to fall into a stream and drown. The flowers she has been collecting symbolize her story, the poppies representing death. Millais painted the lonely setting leaf-by-leaf over many months by the Hogsmill River, Surrey. Afterwards, the artist, poet and model Elizabeth Siddall posed in a wedding dress in a bath of water at Millais’s studio. Through the painting, Millais critiqued the Victorian practice of occasionally arranging marriages for money and status.

Tragicomedy occurred when the candles warming the water went out hours before Millais noticed and poor Lizzie developed pneumonia. Her father threatened a lawsuit and it took a great deal of diplomacy to pacify him. LEARN MORE ABOUT THIS PAINTING

The Awakening Conscience, 1851-53

William Holman Hunt | Beauty as Protest: 1845–1905

A woman is rising from the man’s lap and gazing transfixed out the room’s window. At the center of the painting are her clasped hands – with no wedding ring. As the title suggests, the consciousness of her need for redemption is suddenly awakened. Victorians would have been more alert to the symbolization in this painting. The room is too cluttered and gaudy to be in a Victorian family home; the bright colors and pristine, highly polished furniture speak of a room recently furnished for a mistress, a ‘maison de convenance’, for the gentleman to visit secretly. Around the room are dotted reminders of her “kept” status and her wasted life: the cat beneath the table toying with a bird; the clock concealed under glass; a tapestry that hangs unfinished on the piano; the threads which lie unravelled on the floor; the discarded glove symbolizing prostitution; the marigolds stand for warning and sorrow and the star is a sign of spiritual revelation. Ironically, the model is Hunt’s girlfriend Annie Miller, an uneducated barmaid whom he met in 1850 when she was fifteen, and whom he intended to marry once she was deemed gentile enough – but never did. Her history was not over, though…

Our English Coasts ‘Strayed Sheep’, 1852

William Holman Hunt | Beauty as Protest: 1845–1905

Early on, the Pre-Raphaelites worked en plain air, only possible thanks to the recent invention of tube paints. Devotees of John Ruskin, who exhorted artists to ‘go to Nature in all singleness of heart’, they believed art could teach a moral lesson. He painted this gorgeous landscape on the cliffs overlooking Covehurst Bay, between August and December 1852 in absolutely terrible weather, demonstrating his commitment.

Hunt exhibited the picture at the Royal Academy in 1853 with the title Our English Coasts. The painting could be taken as a satire on the reported defenseless state of the country against foreign invasion. During this period fears of an invasion had been generated by the press, reacting to Napoleon III’s autocratic régime in France. The original frame bore the inscription The Lost Sheep, and when Hunt sent the painting to the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855 he changed the title to Strayed Sheep, thus underlining the picture’s religious symbolism.

Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Cremorne Lights, c1872

James McNeill Whistler | Sensation and Style: 1870–1910

Whistler’s aim in this picture, as in all his Nocturnes, is to convey a sense of the beauty and tranquility of the Thames by night which is hardly surprising as Chelsea Embankment was in the process of being built during his entire tenure there.

The view is from Battersea Bridge, looking upriver towards Battersea on the left and the lights of the Cremorne Pleasure Gardens on the right. Whistler preferred the calm of the river at night to the noise and bustle of the Thames by day. With would set off in a rowing boat at twilight and sometimes remain on the river all night, sketching and memorizing the scene.

LEARN MORE ABOUT ‘ART ON TRIAL’ – WHEN WHISTLER WENT TO ART COURT

LEARN MORE ABOUT WHISTLER’S PEACOCK ROOM DEBACLE

Proserpine, 1874

Dante Gabriel Rossetti | Beauty as Protest: 1845–1905

The English painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti produced at least eight paintings of Proserpine trapped in her subterranean world, the fatal pomegranate in her hand. This lush, sensuous painting appears to bristle with a tortuous, pent-up energy. It is full of peculiar twists and turns. Her neck bulges unnaturally at the back, her hands too are set in an awkward grip. This is a painting of almost tortured stillness: a body under strain.

When he painted Proserpine, Rossetti was entangled in a complicated love triangle. He was completely infatuated with the model for this painting, Jane Morris, who happened to be the wife of his good friend William Morris. When this was painted, the three were living together at Kelmscott Manor. Unable to contain his feelings for Jane, he had given in to temptation and for this was destined to live part of his life in secrecy and withdrawal. Rossetti himself had tasted the fatal fruit and was living with the consequences.

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-86

John Singer Sargent | Art for the Crowd: 1815–1905

This was your Grandfather Smith’s favorite painting. Unfortunately the only photos I have of him looking at it are from behind… In August 1885 John Singer Sargent boating on the Thames when he glimpsed an enchanting scene in a garden at Pangbourne: children lighting lanterns hung among trees, lilies and rose bushes – it became the inspiration for what he came to call his ‘big picture’.

The work is set in an English garden in the Cotswolds, where Sargent spent the summer of 1885 shortly after moving to England from Paris to escape the scandal caused by his 1884 painting Portrait of Madame X.* Every day from September to November 1885, he painted in the few minutes when the light was perfect, giving the picture an overall purple tint of evening. The flowers in the garden died as summer turned to autumn, and they were replaced with artificial flowers. LEARN MORE ABOUT THIS PAINTING

Hope, c1886

George Frederic Watts | Sensation and Style: 1870–1910

Hope is a Symbolist oil painting by the English painter George Frederic Watts. It shows a lone blindfolded female figure sitting on a globe, playing a lyre that has only a single string remaining. The background is almost blank, its only visible feature a single star.

Why did I choose this painting? I suppose it is for sentimental reasons. In 2017 I viewed this with a friend Linda. Her daughter, one of my bridesmaids, had died 4 years previously of breast cancer. She had just finished telling me about Hallie’s last few months and the enormous lengths they had gone to, exploring alternative treatments etc. Our understanding and appreciation of art is so connected to the moment of viewing and at that moment it resonated perfectly with both of us.

Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Cremorne Lights, c1872

James McNeill Whistler | Sensation and Style: 1870–1910

Whistler’s aim in this picture, as in all his Nocturnes, is to convey a sense of the beauty and tranquility of the Thames by night which is hardly surprising as Chelsea Embankment was in the process of being built during his entire tenure there.

The view is from Battersea Bridge, looking upriver towards Battersea on the left and the lights of the Cremorne Pleasure Gardens on the right. Whistler preferred the calm of the river at night to the noise and bustle of the Thames by day. With would set off in a rowing boat at twilight and sometimes remain on the river all night, sketching and memorizing the scene.

LEARN MORE ABOUT ‘ART ON TRIAL’ – WHEN WHISTLER WENT TO ART COURT

LEARN MORE ABOUT WHISTLER’S PEACOCK ROOM DEBACLE

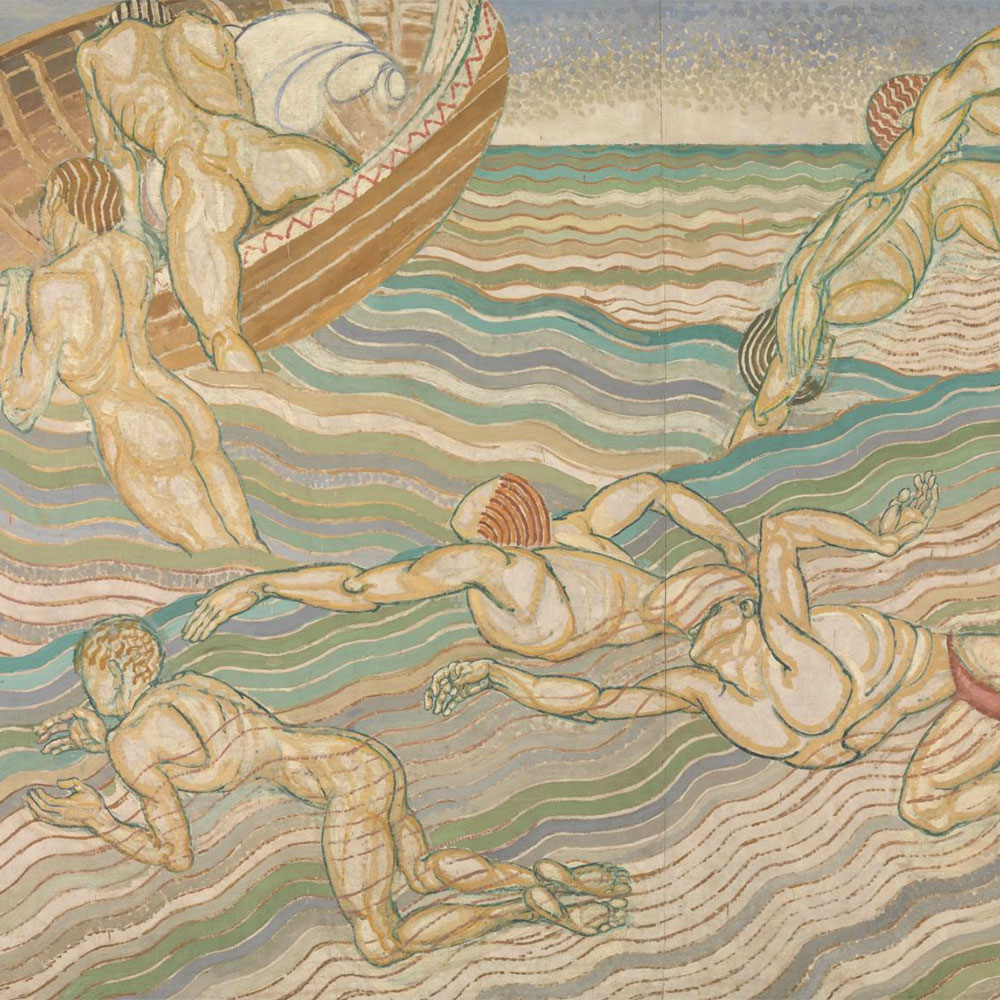

Bathing, 1911

Duncan Grant | Modern Times: 1910–1920

Duncan Grant was a Scottish painter and designer of textiles, pottery, theatre sets, and costumes. He was a member of the Bloomsbury Group.

Based on the theme ‘London on Holiday, he painted this in the summer of 1911 as part of the decoration for the dining room at the Borough Polytechnic, London. From diving into the water to emerging onto the shaky boat, Grant represents the continuous movements of male figures bathing, from diving into the water to emerging onto the shaky boat. His design was inspired by Michelangelo’s male nudes and summers spent at the Serpentine in Hyde Park, which was a site associated with London’s gay culture. The painting was seen as controversial at the time due to its homoerotic implications.

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, c1872

Francis Bacon | Fear and Freedom: 1940–1965

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion is a 1944 triptych painted by British artist Francis Bacon. The canvasses are based on the Eumenides of Aeschylus’s Oresteia, and depict three writhing anthropomorphic creatures set against a flat burnt orange background. It was executed in oil paint and pastel on Sundeala fibre board and completed within two weeks.

The Three Studies are generally considered Bacon’s first mature piece; he regarded his works before the triptych as irrelevant, and throughout his life tried to suppress their appearance on the art market. When the painting was first exhibited in 1945 it caused a sensation and established him as one of the foremost post-war painters.