Ramesses II, The Younger Memnon

Ramesses II, The Younger Memnon

Museum-goers who cast their gaze over Ramesses II may assume that it was stolen. But such an assumption couldn’t be further from the historical truth. At every step of the digging, excavation and transport of the statue, Ottoman elites and Egyptian peasants knew exactly what adventurer Giovanni Belzoni was doing on behalf of British Consul Henry Salt, and they had few qualms about lending their assistance to the cause, so long as they were provided with a form of compensation – wages, diplomatic favors – deemed more valuable than that which was taken away. Not only that, but they often explicitly referred to the assistance they exchanged in such endeavors as a present.

To the Ottomans, such gifts were a no-brainer: something perceived as virtually worthless to them and their subjects could be magically transformed into hard-won political favors with hardly any effort on their part.

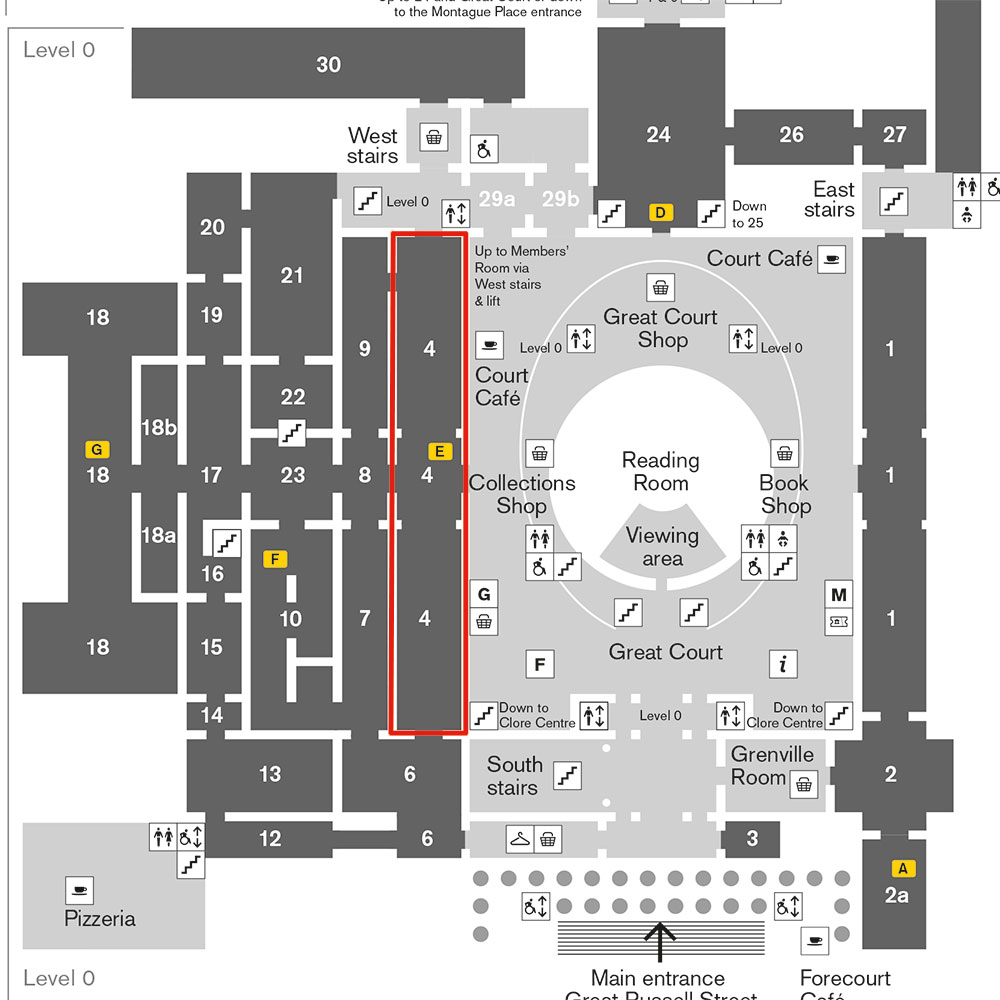

The Younger Memnon is an Ancient Egyptian statue, one of two colossal granite statues from the Ramesseum mortuary temple in Thebes, Upper Egypt. It depicts the Nineteenth Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II wearing the Nemes head-dress with a cobra diadem on top. The damaged statue has since been separated from its upper torso and head. These sections can now be found in the British Museum. The remainder of the statue remains in Egypt. It is one of a pair that originally flanked the Ramesseum’s doorway. The head of the other statue is still found at the temple.

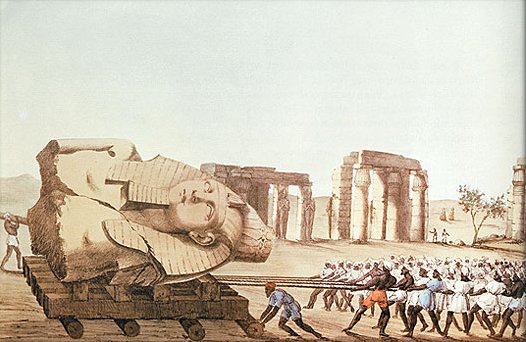

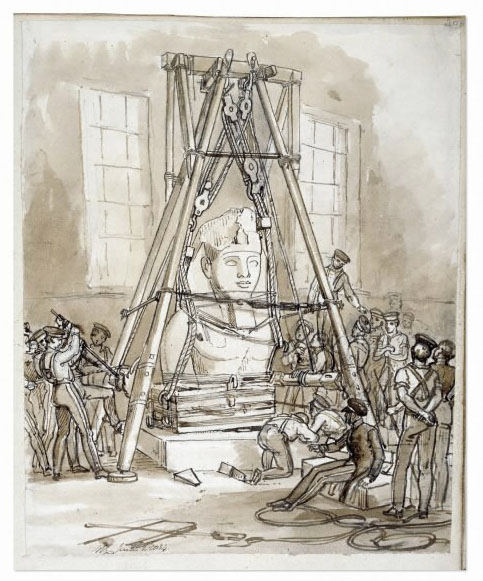

The British Consul General Henry Salt hired the adventurer Giovanni Belzoni in Cairo in 1815 for the digging of the statue and transporting it to Britain. Using his hydraulics and engineering skills, it was pulled on wooden rollers by ropes to the bank of the Nile opposite Luxor by hundreds of workmen.

Anticipated by Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias”, the head arrived in 1818 on Weymouth in Deptford. In London it acquired its name “The Younger Memnon”, after the “Memnonianum” (the name in classical times for the Ramesseum – the two statues at the entrance of the mortuary temple of Amenhotep III were associated with Memnon in classical times, and are still known as the Colossi of Memnon.

Just as the Elgin Marbles diplomatic gift set sail for London, another only slightly less famous one soon followed in its wake. This is the 6.5-tonne exquisitely carved block of granite popularly known as the Memnon Head (the Younger Memnon). Later identified as an ancient Egyptian bust of the great pharaoh Ramesses II, it was one of the first specimens of pharaonic chiselwork to be regarded by Europeans as worthy of comparison to Greek and Roman fine art. It is now installed on top of an unadorned pedestal in the British Museum, visible from any corner of its spacious gallery. The story of its removal to England will once again lay bare all the hallmarks of diplomatic gifts: an unrelated political mission, serendipitous opportunity, unabashed labour in the light of day and zero regret.

Purpose built monumental statues of the pharaoh,

Mary Beard BBC

The Statue of Ramesses II at the British Museum

The Greatest Pharaoh | Ramesses II

In 1801 the French, bombarded by the same British naval and land attack that prompted the sultan to indulge all of Lord Elgin’s desires in Athens, began to withdraw from Egypt. The British army soon followed, leaving the fate of Egypt to be determined by a collection of loosely allied Ottoman combatants. Muhammad Ali, an Albanian military general drawn from the eastern Mediterranean cosmopolitan elite that had long made up much of the upper echelons of the Ottoman state, soon emerged victorious. Before long, he adopted the title of pasha and ruled Egypt as an Ottoman province in name but an independent fiefdom in practice. With political relations between Cairo and Constantinople often tense and adversarial, both the pasha and the sultan were eager to cultivate continued goodwill with both the French and British.

It was within this context that a man named Henry Salt arrived in Cairo in 1816 to take up the post of British consul. One of his first items of business was to apply for a firman from Muhammad Ali that would permit a team of excavators to remove ancient Egyptian antiquities at ancient sites along the Nile. Just as with Elgin in Constantinople, Salt had no trouble procuring such a firman, since the pasha wanted nothing more than to please London’s man in Cairo as a means of cultivating powerful allies. If anything, Salt’s application for a firman was looked upon by Muhammad Ali as merely an appetizer before the main course. Just one year before Salt arrived in Cairo as consul, the Swiss-English traveller John Lewis Burckhardt had tried to convince the pasha to deliver the Memnon Head to the prince regent in England as a present, but the pasha ‘did not consider stone an appropriate gift’.

Note that the pasha did not consider the Memnon Head to be a priceless symbol of the Egyptian nation. Quite the contrary: as a long-neglected hunk of pagan granite, it was perceived to be so bereft of any value that Muhammad Ali did not want to embarrass himself by presuming to give it away as a gift – even to someone who took great pains to suggest otherwise. The result was that the British would have to choose their own diplomatic gift. The man entrusted by Salt with the task of removing the Memnon Head was Giovanni Belzoni, a colorful figure whose chief qualification for the job appears to have been expertise in managing grand hydraulic spectacles in theatrical London productions, such as recreating a naval battle on stage. Belzoni, armed with Salt’s firman, sailed to Luxor and hired a team of local peasants, or fellahin, to help him transport the Memnon Head nearly 5 kilometers (3 mi.) from its resting spot to the west bank of the Nile.

There was nothing secretive about Belzoni’s operations. En route to Luxor, he met the pasha’s son, Ibrahim, whose staff checked his papers. By Ibrahim’s side was the Italian collector Bernardino Drovetti, then serving as the French consul in Cairo. Much like Salt, Drovetti was leveraging the prospect of cosier relations with his homeland – in Drovetti’s case, adopted homeland – to procure the right to remove ancient artifacts. To everyone they met throughout Egypt – be they Arabs, Albanians or Turks, high- or low-born – the terms offered were attractive. Ottoman diplomats found their political prospects brightened by association with the British or French, while Arab peasants procured an attractive supplemental income nearly always at or above market wages – and all for ancient works of heathen art whose only value had heretofore been calculated in terms of its economic value as building materials, as a substitute for manure (as crumbling remains were used as a substitute for fertilizer, as discussed later) or for the elusive gold often believed to be hidden inside.

In addition to both the pasha and his son being acutely aware of what Belzoni and Drovetti were doing, everyone in the vicinity of the Memnon Head clearly saw with their own eyes what was happening. In Belzoni’s own memorable recollection of the removal, in which the Memnon Head appears far larger than its actual size, a veritable army of local fellahin push and pull a makeshift conveyance on wooden rollers built for the massive granite sculpture, tugging it for several kilometers towards the Nile. When it came time to sail downstream back to Cairo with his prize, Belzoni was sent off warmly by the district governor. This man was ‘pleased to hear that I had succeeded in my undertaking, and requested to be remembered to the English Consul, to whom he had sent a letter by me.’ Here again we see the local exchange of political favors, wherein the local governor expects to reap diplomatic rewards for his assistance in helping to organize a work team capable or removing a block of worthless granite. According to Belzoni, the district governor even attempted to refuse his money, in order ‘to make a present’ of the labor of his subjects. Belzoni refused, saying that Salt would not ‘accept such a present’.

Museum-goers who cast their gaze over Ramesses II may assume that it was stolen. But such an assumption couldn’t be further from the historical truth. At every step of the digging, excavation and transport of the statue, Ottoman elites and Egyptian peasants knew exactly what adventurer Giovanni Belzoni was doing on behalf of British Consul Henry Salt, and they had few qualms about lending their assistance to the cause, so long as they were provided with a form of compensation – wages, diplomatic favors – deemed more valuable than that which was taken away. Not only that, but they often explicitly referred to the assistance they exchanged in such endeavors as a present.

To the Ottomans, such gifts were a no-brainer: something perceived as virtually worthless to them and their subjects could be magically transformed into hard-won political favors with hardly any effort on their part.