The Elgin Marbles

THE ELGIN MARBLES

The Elgin Marbles are a collection of classical Greek marble sculptures that were originally part of the Parthenon and other buildings on the Acropolis in Athens. They were removed by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century while Greece was under Ottoman rule and are now housed in the British Museum. The sculptures are a subject of ongoing debate, with Greece seeking their return.

The legality and morality of Elgin’s actions have been questioned, and Greece has consistently requested their return. The British Museum maintains that the sculptures were legally acquired and are important for public access and scholarship. The sculptures are considered masterpieces of ancient Greek art and are seen as symbols of Greek national identity.

But were they at the time? Or is it only since then that the marbles have come to be seen as symbol of national identity?

The notoriety of the Elgin Marbles – fragments of ancient Greek sculpture that once adorned the elevated metopes, frieze and pediments of the Parthenon in Athens – is well known to all. Yet the heated debates about whether or not the sculptures should be returned to Greece all trace their origins back to new ideas that arose in the years after Elgin took them to England. When we examine the historical record concerning the actual course of events that led to their removal in Athens, it is clear that they represent yet another clear-cut case of a diplomatic gift freely tendered.

It is important to stress that there was nothing illegitimate or inauthentic about this state of affairs. Our current fixation on the Elgin Marbles as an enduring symbol of the supposedly eternal Greek nation is a modern distortion fostered by nationalist ideas that only arose in the decades after Elgin’s ambassadorship. Throughout its more than 2,000 years of history, the Acropolis has been home to ancient Greek temples, Christian churches, brothels and Muslim mosques – often with the same building serving each function successively.

The Parthenon was a Christian church for just as long as it was a pagan Greek temple, and it operated as a Muslim mosque for half that time again. There is no single ‘rightful’ identity that can be pulled out of this cultural melange. It was only in the 1820s and ’30s, when European imperial powers decided to privilege the ancient Greek identity over all others as a means of encouraging Greek secession from the Ottoman empire, that the Parthenon came to assume its present symbolism as the quintessential symbol of authenticity for the modern Greek nation.

Losing The Elgin Marbles Will Destroy The World’s Best Museums

Dominic Selwood

Bonnie Greer on the Parthenon sculptures at the British Museum

Why the UK won’t return the Parthenon Marbles

The key to understanding how the Elgin Marbles ended up in the British Museum lies in a proper understanding of just who Elgin was. Born to an ancient and distinguished family, Thomas Bruce inherited his earldom at just five years old. A successful career in the military led to an equally successful career in politics, first as a Scottish peer in the House of Lords and later as one of Britain’s top diplomats in Vienna and Brussels. When Napoleon launched an invasion of the Ottoman province of Egypt in 1798 – motivated in part by a wish to cut off British access to India via the Mediterranean and Red Sea – London responded by dispatching its first permanent ambassador to Constantinople in order to cultivate a closer relationship with Selim III, the Ottoman sultan.

Lord Elgin, advised by his doctor to seek out warmer climes for his health, lobbied successfully for the post. He and his wife arrived in Constantinople in November 1799. To the sultan, the British represented the only realistic hope of getting Egypt back from the French. Thus Lord Elgin, as the chief diplomatic representative of Great Britain, became the primary conduit through which Ottoman gratitude for the British defeat of Napoleon in Egypt would be expressed. The sultan constantly showered Elgin with gifts that posterity has long forgotten about: snuff boxes, medals, horses, furlined cloaks, feathered headdresses and other expensive aristocratic baubles. The one gift that no one has ever forgotten about, however, is his firman.

A firman was a written authorization from the Ottoman government granting its bearer permission to carry out certain activities throughout the empire with the expectation of local assistance. Since Elgin, who fancied himself something of an intellectual and art aficionado, wanted to bring back samples of ancient Greek art for the avowed purpose of stimulating ‘the progress of the Fine Arts in Great Britain’, he applied for a firman that would allow him to do precisely that. But his original request bore little resemblance to the more than 100 tonnes of sculpture that he would eventually remove from the Ottoman province of Greece. In fact, Elgin had only requested authorization for his team of artisans in Athens to make plaster casts of the Parthenon sculptures – not to remove them. Selim III quickly approved the firman.

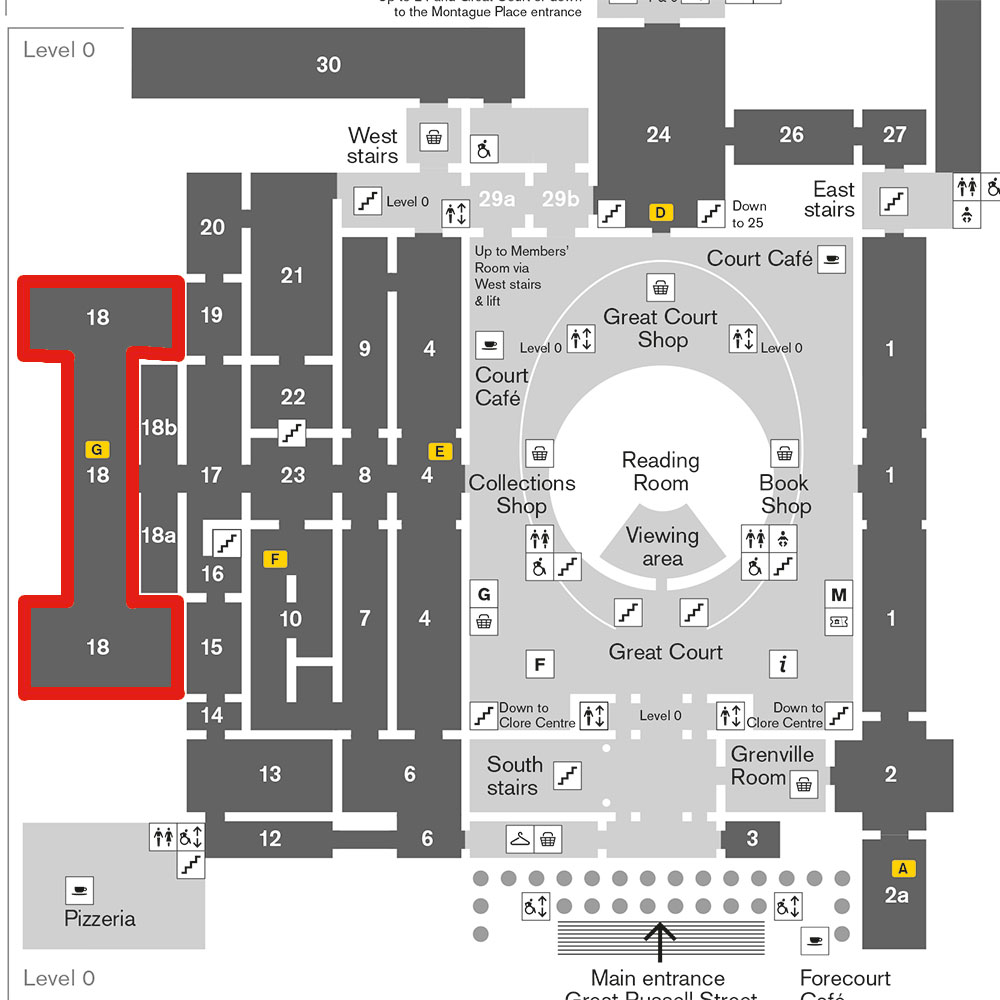

Now the story takes a fascinating turn. Faced with the arrival of Elgin’s team of architects and artists in Athens, the local Ottoman governor turned them away at the base of the Acropolis, the rocky hill which overlooks the city amid a forest of ancient ruins, including the Parthenon. But the reason for their refusal had nothing to do with any notion that the Parthenon was a symbol of the Greek nation that should not be violated by foreigners. Instead, it was only because the Acropolis was then serving as a military citadel for the Ottoman army. That is, it was a strategic military site, with incomparable views of any incoming army or navy that might threaten the city. It was also densely packed with the military barracks and homes of Turkish soldiers and their families, along with a Muslim mosque that had been erected boldly right inside the ruined shell of the Parthenon.

But the Athens of Lord Elgin’s day was quite different. Back then, the majority of those people who would have identified as Greek professed the Eastern Orthodox Christian faith and would have been appalled at the idea that their ancestors, so to speak, had once sacrificed so many oxen in homage to Athena that rivers of blood had flowed by the Parthenon for hours on end. And if they could travel back in time, they would also find that communication was impossible: the Greek language evolved much in the way that Spanish, French and Italian had evolved out of Latin (and no one refers to the Romans as ‘ancient Italians’). Athens itself was a small but cosmopolitan city, with Greek Christians accounting for only about half of its population. And there is no evidence to suggest that any of these Greeks viewed the Parthenon as an inviolable symbol of their ‘nation’: much like the Turkish soldiers in their midst, the Greek residents of Athens frequently quarried the ruins of the Acropolis as building materials for their own homes.

After he was denied access to the Acropolis by the local governor on the authority of his first firman, Elgin applied for a second one. He told the sultan all about the rude handling of his team in Athens. The sultan, incensed that some crumbling pagan marble might sour his relationship with the man who represented his best chance to recover Egypt from Napoleon, quickly issued a second firman and ordered a special envoy to deliver it in person to the local governor in Athens. Not only did the firman again authorize the taking of plaster casts, but it was accompanied by an oral threat from the sultan: if any more complaints reached his ears via Lord Elgin, the military governor’s son would be sent as a slave to the galleys. These threats completely changed the balance of power in Athens. As Philip Hunt, a chaplain engaged by Elgin for his team in Athens, wrote, the local governor ‘is now submissive to all our views in hopes of your speaking favourably for him’ to the sultan.

Sensing an opportunity, Hunt decided to reach for the stars: instead of plaster casts, might the sultan’s favourite ambassador in Constantinople now be allowed to remove the original sculptures themselves? Aware that the sultan cared far more about the recovery of Egypt than a collection of ancient pagan sculptures that no one had tended for millennia, the governor agreed. But there is no reason to suppose that this was a secret operation, carried out under cover of dark, with objects spirited away as clandestine cargo in unmarked ships. A watercolor by Edward Dodwell, who witnessed at first hand the process of removal in 1801, shows local men hired by Elgin’s team lowering a metope to the ground with rope under a cloudy but bright sky, as two well-dressed Turks (likely officials) sit on the ground nearby and smoke their pipes. The mosque, a symbol of a very different cultural orientation than we are used to associating with the Parthenon today, appears prominently inside the colonnade.

In addition to being removed in broad daylight from the single most conspicuous and exposed site in all of Athens, these marbles also would have had to be laboriously transported to the nearest seaport, in full view of Ottoman officials and curious onlookers.

To label the Elgin Marbles a form of military plunder is a gross perversion of historical fact. On the contrary, Elgin was the human embodiment of the exact opposite: his presence in Constantinople represented a military alliance between the British and Ottomans. And the sculptural programme he was permitted to remove from the Parthenon was a direct material extension of this alliance. Like many diplomatic gifts, such as was the case with Hoa Hakananai’a, the Elgin Marbles were not the result of a premeditated imperialist conspiracy. Permission to remove them arose from a serendipitous convergence of fluid developments on the ground while carrying out a very different political mission altogether. And both sides left the encounter in high spirits: Elgin got his marbles and the sultan got his Egyptian province back. Rarely has any diplomatic gift of art been so easy to identify as such.