V&A, VICTORIA & ALBERT MUSEUM | MAP | FREE – Check on Free Tours DIGITAL MAP

Open: Daily: 10am – 5:45pm, Friday: 10am – 8pm (some galleries close after 5:45pm)

This is my favorite museum in the whole world (besides the Wallace). You can and should plan to spend all day here. Look at stuff ’til your eyes pop out. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London is the world’s largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects, spanning 5,000 years of art, from ancient history to the present day, from the cultures of Europe, North America, Asia and North Africa. The V&A can be absolutely overwhelming. This tour is designed to narrow the focus a bit to help move you through this massive space.

Slavery & Empire Tour

Many of the objects in the V&A were lovingly collected and gifted/sold to the museum. Some were plundered and sold to the museum. However the V&A acquired the objects, the wealth necessary for collecting, commissions and expeditions was very likely entwined with slavery and/or the colonization of India. Let’s explore some previously neglected, ‘simultaneous’ histories. ** WARNING: you may find some objects abhorrent in nature **

The British and Dutch East India Companies were both powerful chartered companies that played significant roles in global trade, the slave trade and brutal colonialism during the 17th-19th centuries. The majority of European luxury objects from the 17thc and on can be traced back to the profits from slavery in the West Indies and/or colonization in India or Africa. Between 1662 and 1807, British colonial ships were involved in transporting approximately 3.4 million Africans to the Americas, nearly 1/3 of all transported slaves. Of these, about 2.96 million survived the journey and were sold into slavery. The British slave trade was a major part of the transatlantic slave trade, with British ships accounting for the second-highest volume of enslaved people transported. India was also a source of exploitation. British colonial rule extracted an estimated $45 trillion from India between 1765 and 1948, as well as reducing India’s GDP from 4% to 0.4%. This massive drain of wealth was achieved through various mechanisms, including taxation, trade imbalances, and appropriation of resources.

How it relates to the current exhibit: Cartier

The Manchester Tiara

ca. 1903 (made), Cartier, Paris

The Sainsbury Gallery | MAP

The Sainsbury Gallery is currently holding the Cartier Exhibit – for which you will need a ticket. All that Glitters… The Manchester Tiara was made by Cartier, Paris, in 1903 to the order of Consuelo, Dowager Duchess of Manchester. Cartier’s records note that she supplied over a thousand brilliant-cut diamonds and more than 400 rose-cut diamonds, while Cartier supplied further rose-cut diamonds and the paste stones which make up the scrolls at the end of each side.

The Duchess had been born María Francisca de la Consolación “Consuelo” Yznaga to slave-owning families on both sides. Her father owned one of the largest sugar plantations in Cuba with over 30,000 slaves working in the mills. Her mother’s family owned the Ravenswood Plantation in Louisiana with 145 slaves. With a dowry of $6 million, the Duchess was married to the inebriate George Montagu, 8th Duke of Manchester. By 1882, he had spent so much of his wife’s dowry on gambling and mistresses, that his father the 7th Duke, banished the couple to their Irish estates. Manchester died in August 1892 of cirrhosis of the liver aged only 39.

TOUR BEGINS, LEVEL 4:

Enter through the Cromwell Road entrance. The entrance hall has a huge glass sculpture by Dale Chihuly hanging from the dome. Once you walk in, turn left and find the elevator. Go to the top floor – we are going to work our way down. My tour starts on the fourth floor (top floor) in ceramics.

Turn right from elevator and walk down to Gallery 136 – is a corner. You are looking for a Chinese porcelain figure of lady known as Madame de Maintenon.

Chinese porcelain figure of lady (Madame de Maintenon)

China (Jingdezhen), Qing dynasty, Kangxi period, ca. 1700

Room 136, The Curtain Foundation Gallery | MAP

At first glance, this looks like merely another porcelain figurine in 18th century European dress. Look a bit closer at the face. Chinese porcelain craftsman had most likely never laid eyes on a European woman – but needed to create figures for export all the same. Once trade routes with the East were established in the 17th century, Europeans went mad for porcelain. At this time, the secret for creating fine porcelain had not been discovered by Europeans yet – the materials and technique required was a secret strictly guarded by the Chinese. This figurine is possibly modeled after European engravings, with Chinese decorative motifs added on by the Chinese craftsman.

Turn around and walk back to Room 139 – there are three objects for you to find here.

Punch Bowl

ca. 1763, Liverpool

Room 139, The Curtain Foundation Gallery | MAP

Between c. 1720 and 1807 Britain dominated the transatlantic slave trade, yet throughout the same period material representations of the trade remained markedly few. A demand for Liverpool ceramics depicting slave ships did, however, develop in the later 18th century. These artifacts provide important insights into both the aspirations of those directly involved in slave shipping, and contemporary understandings of the slave trade itself. They also point to the emergence of an actively pro-slavery material culture: a direct response, it may be argued, to the propagandist strategies adopted in the 1780s by the abolition movement.

The Swallow made nine slaving voyages and was owned by John Dobson, one of the most prolific slaving merchants in 18th-century Liverpool. It is estimated that the ships of Liverpool merchants transported about 1.4 million enslaved Africans, over 10% of the total number. One interesting feature of this punch bowl is the pink-hued enameling. Few ceramic artists had ever seen the trade they depicted, and as a result they created euphemistic images embodying the disjuncture between the elaborately rigged slave ship and the realities of the trade in which that ship was engaged. The outcome was a maritime art that was rose tinted and in the case of Swallow with the pink enameling, quite literally; a metaphor encapsulating 18th-century understandings of the slave trade itself.

Uncle Tom with Eva

ca. 1852, Staffordshire

Room 139, The Curtain Foundation Gallery | MAP

This Staffordshire figure group represents ‘Uncle Tom’ and ‘Eva’, two characters from the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin by the American author Harriet Beecher Stowe, which was first published in serial form in 1851. The novel focuses on the tale of Uncle Tom, a long-suffering African American enslaved man. Eva is a white girl whom he rescues from drowning then is employed by her family at their plantation.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the best-selling book of the 19th century and is often credited as a driving force behind America’s anti-slavery movement. However, the influence of racism is evident in the way in which characters in the book are reduced by both novelist and illustrator to racial ‘types’. The character of Uncle Tom, in particular, who passively accepts his fate, contributed to the negative stereotyping of black people.

Tobacco Jar

ca. 1840-1850, Staffordshire

Room 139, The Curtain Foundation Gallery | MAP

In Britain tobacco remained strongly associated with black Africans and the apothecaries in which it was sold frequently used a wooden figure of a ‘Blackamoor’ to promote their wares. This tobacco jar, produced in Staffordshire, England, is in the form of a black child who wears an apron and is polishing a boot. In the 18th century it had been considered fashionable in wealthy homes to employ a black servant, especially a young boy, but by the mid 19th century, influenced by slave revolts in the colonies and the British anti-slavery movement, the fashion was less prevalent.

Keep walking to Room 145.

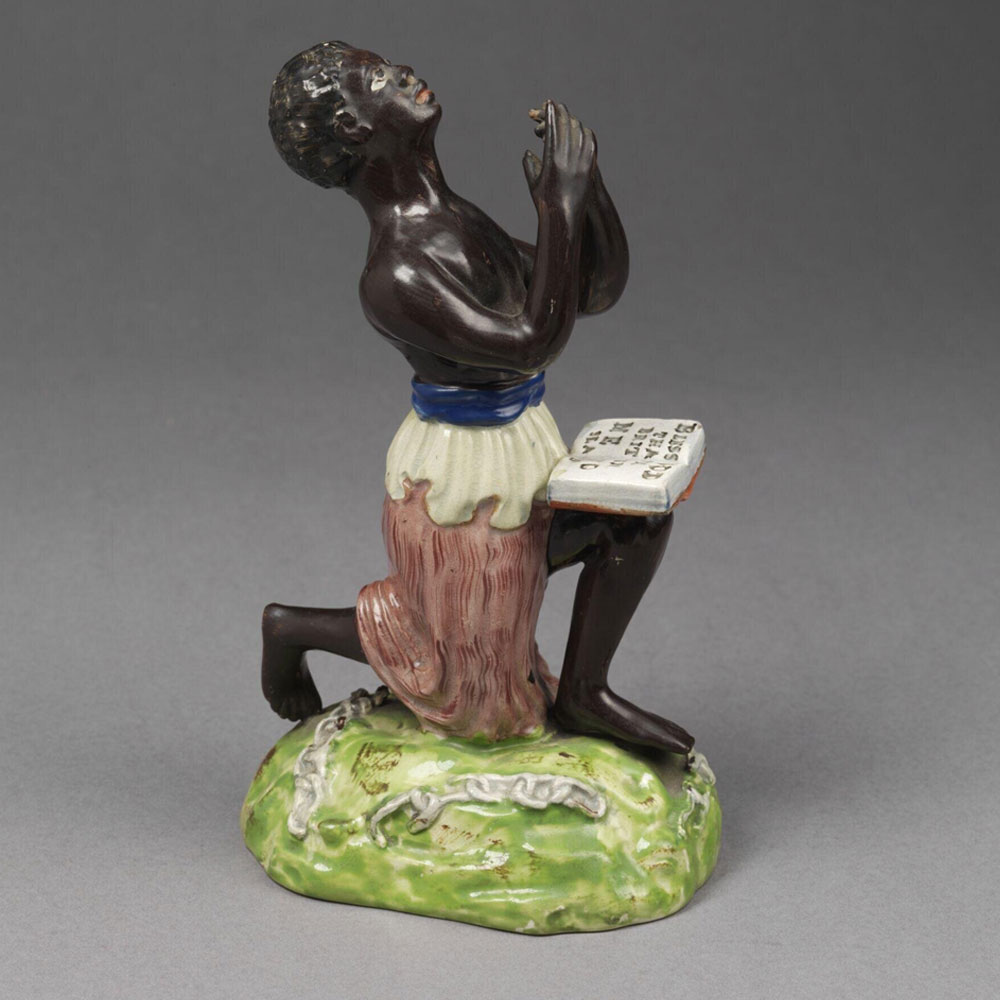

Freed Slave

ca. 1833, Staffordshire

Room 139, The Curtain Foundation Gallery | MAP

Though the Slave Trade was abolished in 1807, Slavery itself was not abolished until 1833. This figure was created to commemorate the Act of Parliament which ended slavery in the British Empire. Credit for ending British slavery was awarded to a small group of middle- and upper-class Christian humanitarians, led by William Wilberforce, and the active role played by many Africans in resisting slavery went largely unrecognized. Similarly, in contemporary depictions of slavery, slaves were often depicted as passive figures. This figure is typical in showing a black slave kneeling in gratitude, surrounded by his broken chains. His open book reads ‘BLESS GOD / THANK BRITON / ME NO SLAVE’.

The British government paid £20 million in compensation to slave owners as part of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. This compensation was for the loss of their “property” (the enslaved people) and was a key part of the legislation that abolished slavery in most British colonies. The loan to finance this compensation was not fully repaid until 2015.

LEVEL 3:

Keep walking to Walk back to Room 144. Take the stairs down to Level Three. Take a left and find Room 131. There are three objects for you to find in here. The wine glass is near the far end of the room on a top shelf as I recall.

Wine Glass

ca. 1735 – 50, Netherlands

Room 131, Glass | MAP

This Dutch wine glass is engraved with a hidden message of love between two men. The engraving depicts the Bible story of two intimate friends – David and Jonathan – embracing as they part forever. The inscription suggests friendship, but the gesture of one man stepping on the other’s foot would have been understood by those in the know as a sexual invitation. Made at a time when gay men were prosecuted in the Netherlands, a toast to friendship was a safe way to celebrate love between men.

I chose this object more for the general intolerance and oppression so many faced and still face today.

Glass Beads

ca. 19th century, Venice

Room 131, Glass | MAP

These glass beads are of the kind known as ‘trade’, ‘aggry’ or, sometimes, ‘slave’ beads. They are usually associated with West Africa but were originally created in Europe, particularly Venice, Bohemia and the Netherlands. The history of trade beads dates to the 15th century when Portuguese trading ships arrived on the coast of West Africa to exploit its many resources, including gold, slaves, ivory and palm oil. At that time, beads were a major part of the currency exchanged for people and products. The cost of producing the beads declined as glassmaking technologies developed and, for Europeans, the beads provided a cheap and efficient means of exploiting African resources.

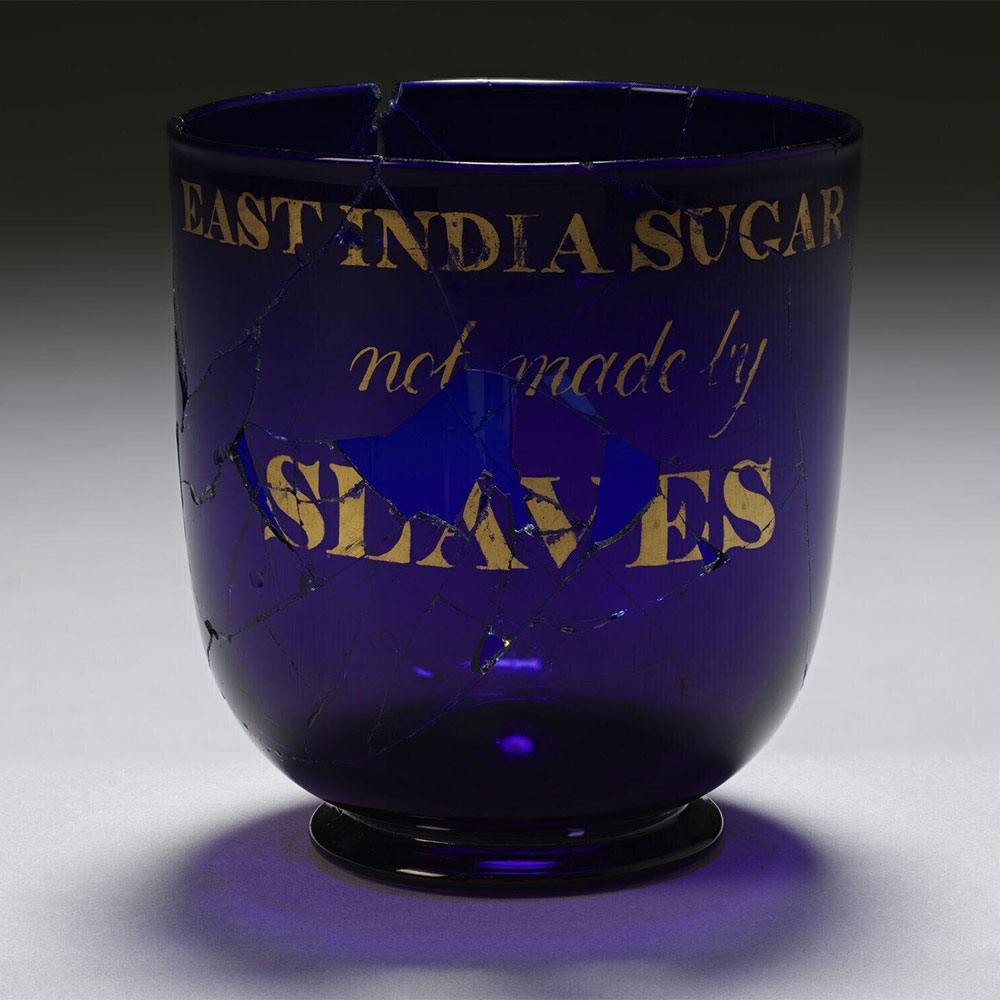

Sugar Bowl

ca. 1820-30, Bristol

Room 131, Glass | MAP

This extremely rare blue glass sugar bowl, dating from 1820-30, and inscribed with the message ‘EAST INDIA SUGAR / not made by / SLAVES’, is an important material remnant of the boycotting of sugar produced through exploitative labour practices.The bowl is one of possibly only two known examples, the other being in the British Museum (museum no. 2002,0904.1) and enclosed within an associated wooden tea caddy, signifying the place of these objects within the 18th and 19th century social practice of tea and coffee drinking. Like the many other ceramic objects which convey the same messages, this object would have allowed men and women sympathizers of the abolitionist movement to signal their support in social settings as they mixed with acquaintances and engaged in topical conversation.

LEVEL 3: Getting to the next room is a bit goofy. Go back to Room 127 and take a right into the hallway. You’re going to walk around the U-shaped balcony until you come to Room 126. Enter and go to Room 125, British Galleries (1760-1900).

We’re going to go backwards chronologically.

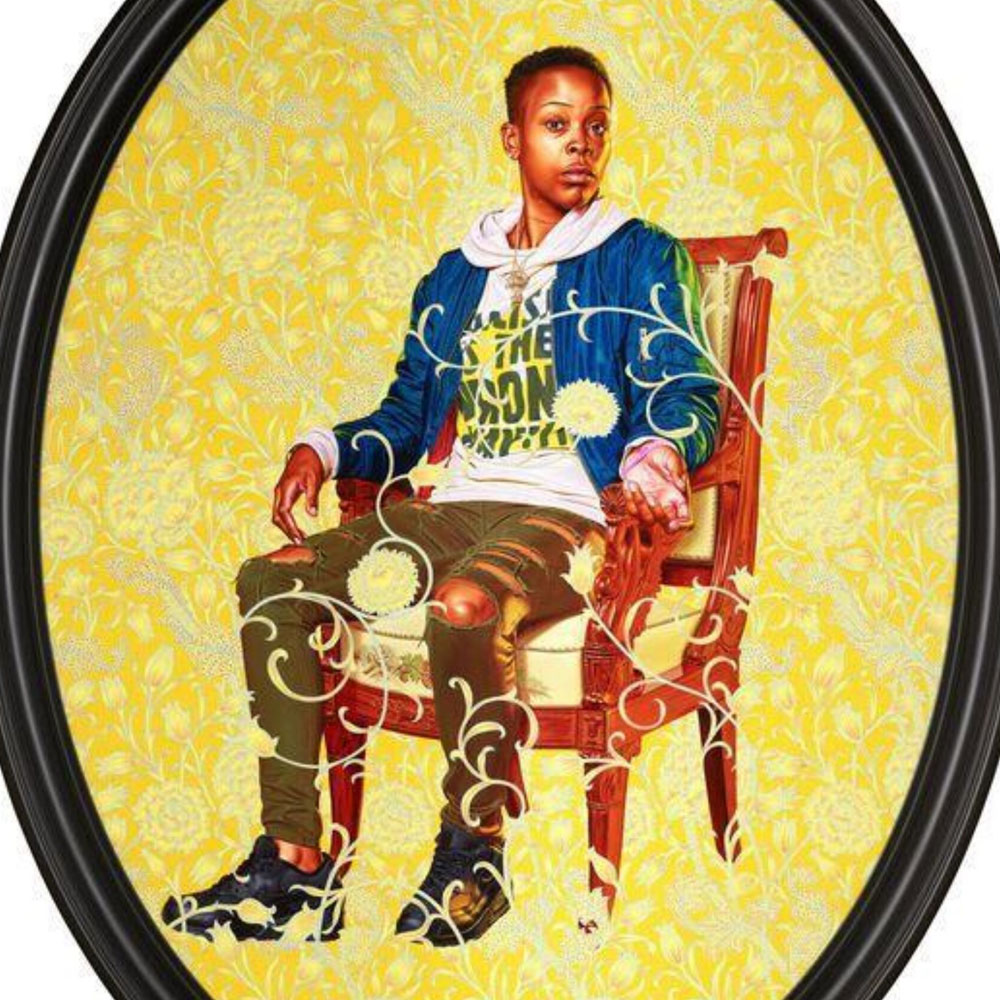

Portrait of Melissa Thompson

ca. 2020, Kehinde Wiley, Painter

Room 125, The British Galleries (1760-1900), Edwin and Susan Davies Gallery | MAP

Nigerian-American artist Kehinde Wiley places people that are marginalized and underrepresented at the centre of his work. In 2019, Wiley came across Melissa Thompson in Dalston, east London, and invited her to sit for this portrait. The style of the painting and her pose recall classical European portraits of white, privileged sitters. Thompson’s presence subverts traditions, raising important questions about race, gender, identity and representation in art. The yellow backdrop is directly inspired by William Morris’s 1884 ‘Wild Tulip’ design, displayed nearby.

Wild Tulip Wallpaper

ca. 1884, England

Room 125, The British Galleries (1760-1900), Edwin and Susan Davies Gallery | MAP

William Morris (1834-1896) was an English textile designer, poet, artist, writer, and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement. He was a major contributor to the revival of traditional British textile arts and methods of production. Raised into a wealthy middle-class, his childhood, schooling and earliest endeavors relied upon income from the copper mines at Devon Great Consols. He developed a keen interest in medieval history and medieval architecture, tied to Britain’s growing Medievalist movement, a form of Romanticism that rejected many of the values of Victorian industrial capitalism. Morris adopted a philosophy of rejecting the tawdry industrial manufacture of decorative arts and architecture in favor of a return to hand-craftsmanship, raising artisans to the status of artists, creating art that should be affordable and hand-made, with no hierarchy of artistic mediums. Near the end of his life, he advocated for improved housing for workers, free compulsory education for all children, free school meals and an eight-hour working day, among others reforms.

LEVEL 3: Walk to Room 120

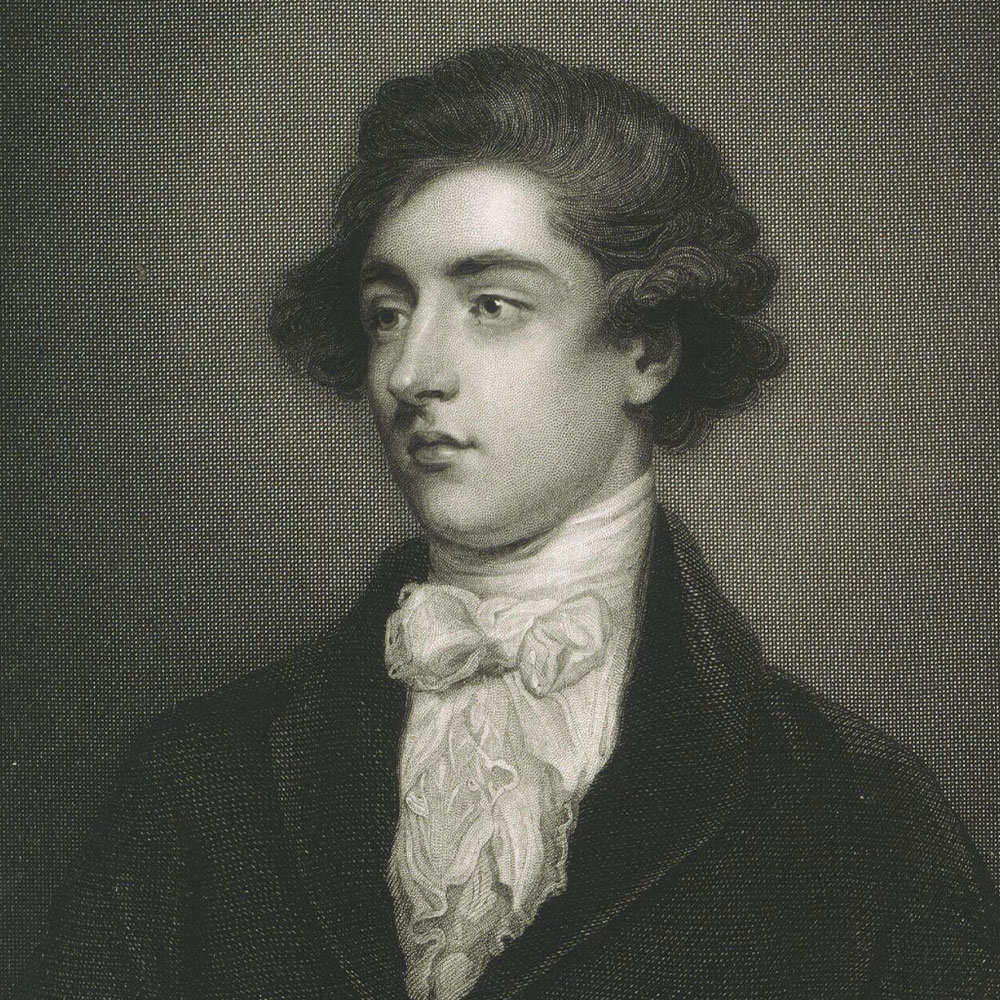

William Beckford, Print

ca. early 19th century (printed), Joshua Reynolds, Painter

Room 120, The British Galleries (1760-1900), The Wolfson Galleries | MAP

This print, from an oil painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds shows William Beckford at the age of 21. Beckford was one of the great collectors and patrons of his era. To house his collections, he built a vast Gothic extravaganza known as Fonthill Abbey.

The enormous wealth on which Beckford’s lifestyle depended came from the exploitation of enslaved Africans. His father was England’s first sugar plantation millionaire and his mother was the widow of Francis Marsh, another Jamaican planter. With the abolition of slavery, however, the Jamaican plantations ceased to be profitable. Falling sugar prices caused Beckford to sell some of his estates, but the income raised by the devalued plantations was not enough to meet his debts. Forced to sell Fonthill Abbey and its contents, he retired to Lansdown Crescent, Bath, with a small selection of his art. He died at Bath in 1844.

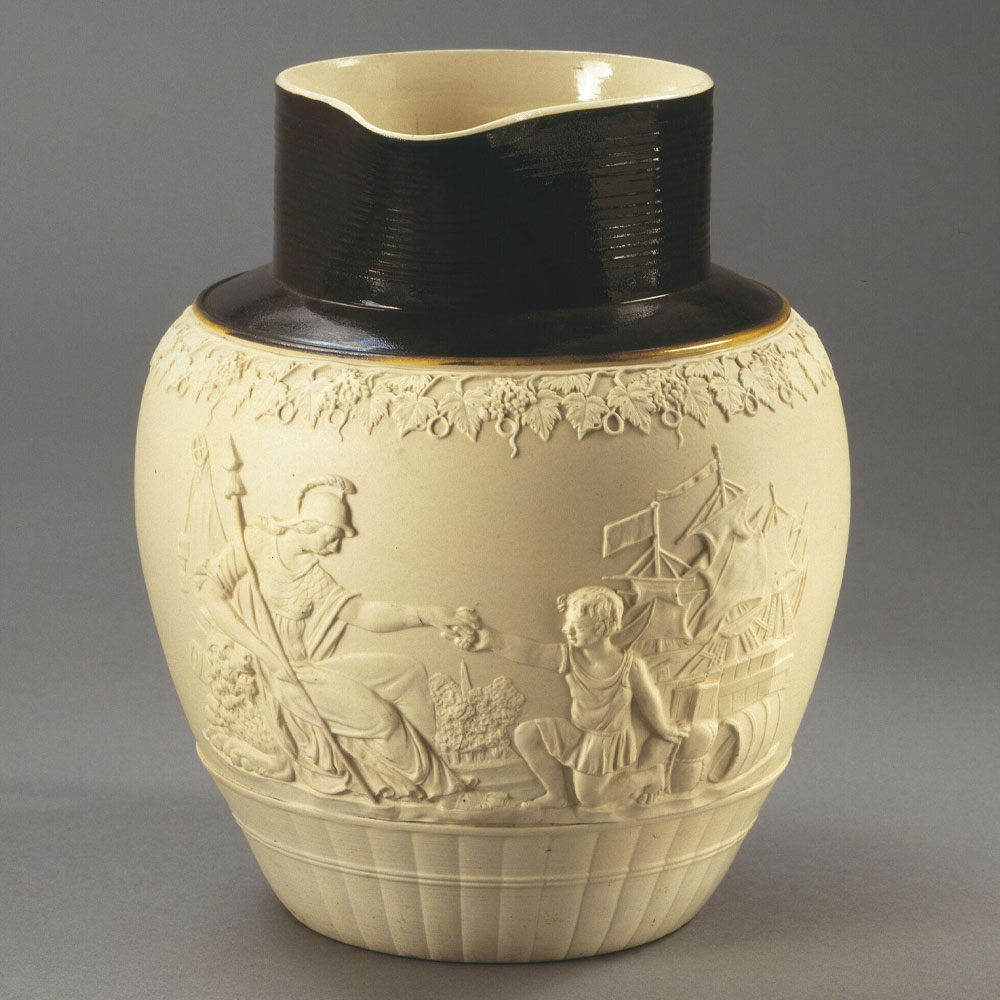

Jug

ca. 1800, Lane End

Room 120, The British Galleries (1760-1900), The Wolfson Galleries | MAP

This jug represents Britannia offering comfort to a slave. It links a traditional patriotic symbol with the new movement for the abolition of slavery. After the loss of the American colonies in 1783, attitudes in Britain to slavery began to change rapidly. The British slave trade was finally abolished in 1807.

The use of beer jugs to promote political causes extended back to the 1770s, when overglaze black prints in huge profusion were added to creamwares and Pearlwares. The motifs on spigged white stonewares were, however, usually allegorical or concerned with sports and pastimes. This apparently unique and slightly ambiguous jug may have therefore been commissioned by a prosperous client involved in the anti-slavery campaign, which was highly unpopular in many quarters, for example seaports such as Bristol and Liverpool, both busily involved in the transatlantic slave trade.

LEVEL 3: Walk to Room 118

Wedgewood, ‘First Edition’, Portland Vase

ca. 1790, Staffordshire

Room 118, The British Galleries (1760-1900), The Wolfson Galleries | MAP

Josiah Wedgwood (1730–95) was a uniquely important potter who combined as much an interest in science as he did in marketing. The Portland Vase, a Roman cameo-cut glass vase of about 40–30 BC, was one of the most celebrated classical antiquities in Wedgwood’s day.

He was a prominent abolitionist who actively campaigned against the slave trade. He is best known for producing the “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” anti-slavery medallion (V&A’s currently on loan I believe), which became a powerful symbol of the movement. While Wedgwood’s company also produced luxury ceramics that were bought by people who profited from the slave trade, and he indirectly benefited from the trade, he was a vocal opponent of slavery and played a significant role in the British abolitionist movement.

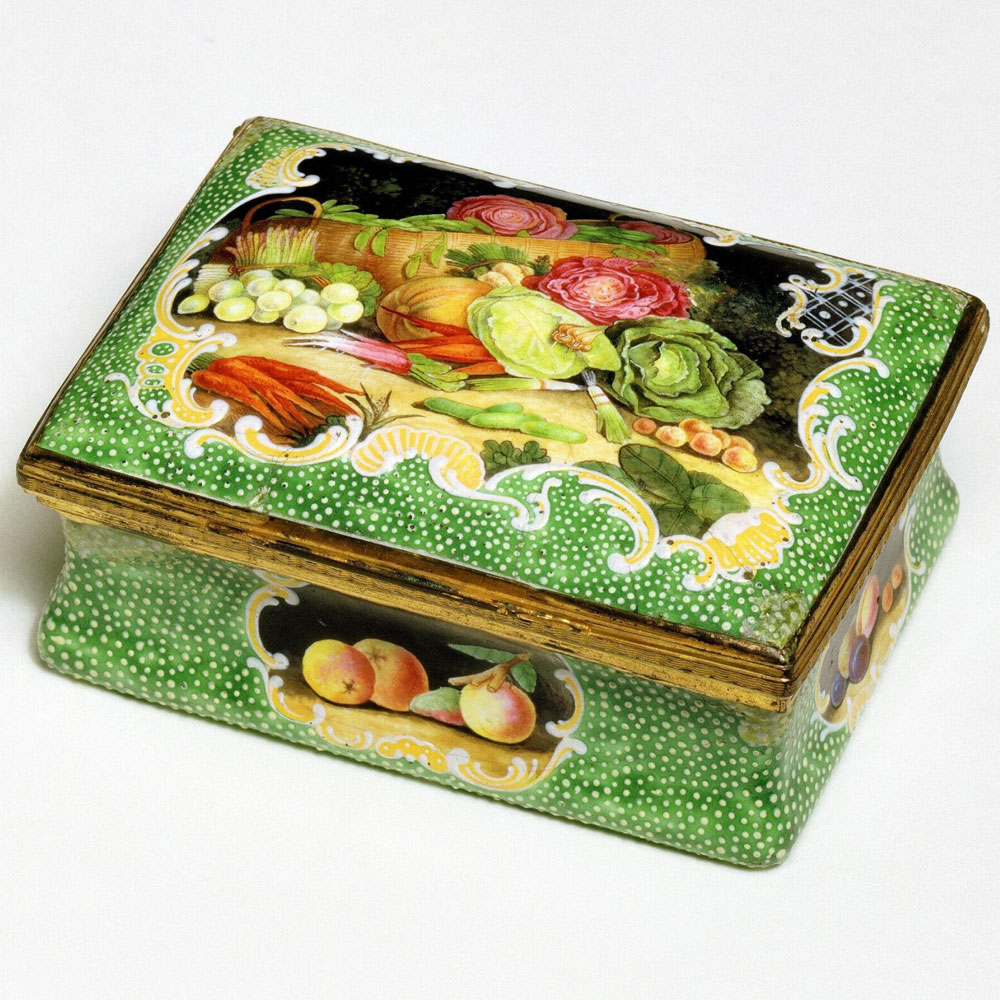

Snuff Box

ca. 1765-1775, Birmingham

Room 118, The British Galleries (1760-1900), The Wolfson Galleries | MAP

Snuff was manufactured in Britain using imported tobacco which was milled to the appropriate texture and often had flavourings added such as vanilla, rum or spices. The tobacco itself was part of the triangular transatlantic slave trading route and came back to Britain from the Americas, especially Virginia, and some Caribbean islands. The tobacco was grown on plantations using enslaved labour. By the 1700s the use of snuff was at a peak and considered a fashionable habit amongst the elite stimulating the demand for accessories, like snuff boxes, that were often highly decorative luxury items.

Raised Rococo scrolls enclose panels on the lid and four sides of this box. Each panel is deftly painted with groupings of fruit and vegetables. Although vegetables are very unusual on English painted enamels, there was a vogue for vegetable-shaped porcelain tableware in mid-18th-century Britain.

LEVEL 3: Duck into Room 118a (alcove).

The Garrick Bed

ca. 1775, Thomas Chippendale Senior (maker), London

Room 118a, The British Galleries (1760-1900) | MAP

This four-poster bed, named after the celebrated actor and theatrical manager David Garrick is dripping with vestiges of the British Empire. It was made in the workshops of Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779), one of the most influential British furniture-makers. The decoration, inspired by Chinese wallpaper, was enhanced by the prospect of the couple’s garden with its mature willow tree. The original Indian chintz hangings were presented to Mrs Garrick in 1775 by friends in Calcutta. They were of dyed and painted cotton, made in Masulipatam, Madras, in an East India Company factory. As there was a ban on the import of Indian Cotton to protect British wool and silk manufacturers from competition, the hangings were seized by British Customs’ officials and David Garrick had to plead to recover them. India, particularly Bengal, held a dominant position in the global cotton textile market at the time, producing high-quality and affordable fabrics like chintz. The ban also served a larger purpose of controlling trade dynamics to Britain’s advantage, undermining India’s indigenous craftsmanship and ensuring India remained a supplier of raw materials and a consumer of British manufactured goods.

LEVEL 2:

Go down the stairs outside Room 118 to Level 2. Walk through Room 74, Design 1900-Now to Room 74a and turn left. Walk through Gold, Silver & Mosaics until you get to 70a. This is the Silver Hallway – which is utterly magnificent. Walk through until you get to the center, Room 67 and look for the next object – an Epergne with an elephant at the base.

Epergne

ca. 1869-1870, Barnard & Sons (maker), London

Room 67, Silver | MAP

This is cultural apprpriation at its finest. The silver centerpiece is in the naturalistic style and consists of two crossed and interlacing palm trees which form the support for the glass bowl. The trees spring from a matted and rusticated ground and clustered round them a two sepoys, one sitting, one standing, and an Indian elephant. This was a retirement gift to S.B.Partridge, previously Honorary Surgeon to the Queen. In addition, he was created a Companion of the Indian-Empire. He also received a medal & clasp for Burmah & a medal and clasp for the siege and recapture of Lucknow. He was also a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, and academic professor at educational establishments in India. He was associated with the Bengal Army Medical Service from 1852 until 1893. He died in 1898.

LEVEL 2: Walk down to Room 89 and turn right into Room 83. Walk through Gold, Silver & Mosaics until you get to a gold crown.

Gold Crown

ca. 1740, Unknown, Ethiopia

Room 83, Sacred Silver & Stained Glass | MAP

This crown was probably given to the Church of Our Lady of Qwesqwam, near Gondar, as a gift from King Iyyasu II and his mother Empress Mentewwab, along with a gold chalice also in the V&A collection. Iyyasu II ruled from 1730 to 1755. Around the two lower tiers of the crown are images of the twelve Apostles, Christ’s closest followers. On the top section are the four Evangelists – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John – who wrote the Gospels. The crown and chalice were looted by British troops following the destruction of Maqdala (Magdala) by the British Army in April 1868. They were deposited at the South Kensington Museum (later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum) by H.M. Treasury in 1872.

LEVEL 2: Walk back to Room 89 and go through to Room 90 and then through to 90a – the Miniatures Room. The Miniature Room can be heavenly on a hot summer day. Usually empty, always quiet, deliciously dark. The miniatures are moved in and out of conservation quite often – don’t be surprised if one has been removed.

Henry Swinburne

ca. 1775-1780, Richard Crosse (artist), England

Room 90a, Portrait Miniatures, The International Music and Art Foundation Gallery | MAP

Henry Swinburne (1743–1803) was an English travel writer and slave owner. His wife Martha’s wealth came entirely from slave plantations in the West Indies. In 1783, her property suffered enough loss that the French Government granted them a grant of all uncultivated crown lands in the island of St. Vincent valued at £30,000. In 1801 he obtained the lucrative post of vendue-master in the newly ceded settlement of Trinidad, and also as commissioner to deliver up the Danish West Indian islands to a Danish official. He died from sunstroke at Trinidad on 1 April 1803.

LEVEL 2: Now keep walking straight into the Jewellery Galleries, also dark, cool and mysterious. You are looking for 2 objects.

The Heneage Jewel, Locket

ca. 1600, Nicholas Hilliard (painter), England

Room 91, Jewellery, The William and Judith Bollinger Gallery | MAP

The Heneage Jewel is decorated with a profile bust of Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) in gold. Although Elizabeth’s character and talents have often been a matter of controversy, the ‘age of Elizabeth’ has been celebrated not only for Shakespeare and its contribution to the English Renaissance but for its place in British religious, maritime and imperial history. A full account of her reign must include her support for the slave trading voyages of Sir John Hawkins in the 1560s and her approval of a failed venture in 1596 to ‘capture and forcibly deport’ people of black African descent living in England ‘shipping them to Spain or Portugal to be sold as slaves or exchanged for English prisoners of war’.

Ring

ca. 1500 BC-1400 BC, Egypt

Room 91, Jewellery, The William and Judith Bollinger Gallery | MAP

The scarab beetle was thought to be an incarnation of Khepri, an Egyptian sun god associated with resurrection. This ring forms part of a collection of over 600 rings and engraved gems from the collection of Edmund Waterton (1830-81). Edmund Waterton used the fortune which was made by his family’s involvement in the British Guiana sugar plantations to put his collection together. His grandfather owned a plantation known as Walton Hall and his father, Charles Waterton, went to Guiana as a young man to help run La Jalousie and Fellowship, plantations which belonged to his uncles. When slavery was abolished in the British territories, Charles Waterton claimed £16283 6s 7d in government compensation and was recorded as having 300 slaves on the Walton Hall estate.

LEVEL 2: Walk through to there end of Jewellery and take a left into Room 107 – more of a hallway. About half way down the hallway is a ‘bridge’, Room 111 – with some sculptures on it.

Alderman William Beckford, Lord Mayor of London

ca. 1770, Nathaniel Smith (designer and maker), London

Room 111, The Gilbert Bayes Gallery | MAP

The subject William Beckford was baptized in Jamaica in 1709. He was the grandson of Peter Beckford (bap. 1643, d. 1710) who travelled to Jamaica as a young man and became the founder of the greatest sugar fortune in the West Indies. William inherited the majority of his family’s vast Jamaican estates, which included complete ownership of eleven sugar plantations and at least 1737 slaves. By the time of his death this had been extended to thirteen sugar plantations and approximately 3000 slaves. His son, William Beckford, inherited the slaves and plantains at the age of 21 and became a known art collector but unlike his predecessors, William never set foot on the island.

A Captive

ca. 1660-1700, Unknown, France

Room 111, The Gilbert Bayes Gallery | MAP

France colonized islands in the West Indies in the 17th century, with the aim of transforming them into profitable sugar-producing economies fueled by the labour of enslaved Africans. French involvement in the transatlantic trade continued to grow over the following century, but in 1791 there was a massive slave revolt in Saint-Domingue, one of the most profitable colonies. On 1 January 1804, the territory became Haiti, the first black republic.

This decorative bronze figure was made in France in the 1660s, during the reign of Louis XIV, whose chief minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, was the architect of French colonial policy.

LEVEL 1:

Walk through Room 111 and turn right onto the Ironwork balconies. Once you are past the Dome (center) take a left into Room 116. Walk through and go down the stairs. Walk into The British Galleries (1500-1760). Keep walking through The British Galleries (1500-1760). You are looking for Room 54.

A Harlot’s Progress, Etching and Engraving

ca. 1732 (printed and published), William Hogarth (artist), London

Room 54, The British Galleries (1500-1760), Henrietta Street Room | MAP

William Hogarth, like many of his contemporaries, was critical of those who derived their wealth from transatlantic trade, and also of the fashion for transatlantic commodities. He used his skills as an artist and printmaker to satirize the moral weakness which he saw in those who consumed these ‘foreign’ goods and to expose the levels of exploitation at work in London, then trading capital of the world. Often he used black figures in his images as rhetorical devices to underline the lack of ‘civilization’ amongst those apparently responsible for spreading it throughout the colonized world. The upright pose of the page and his widened eyes invite us to consider this scene of immorality from his perspective.

LEVEL 1: Walk back through The British Galleries (1500-1760) towards the big entrance hall. You are looking for Room 56c – a little alcove.

Tortoiseshell Combs & Case

ca. 1673, Paul Bennet (maker), Jamaica

Room 65c, The British Galleries (1500-1760) | MAP

In the 17th century entrepreneurial British adventurers from all levels of society journeyed to the Caribbean, with ambitions to make their fortunes from the emerging sugar industry there. This new ‘Plantocracy’ – the successful plantation owners who were regarded as the dominant class – commissioned luxury objects to promote their elevated status back home. Gifts symbolizing success were made of exotic materials, and tortoiseshell items, like these combs, were particularly prized as the raw materials were unavailable in Britain, making them enviable tokens. We think these may have been commissioned by Lady Lynch, wife of the Governor of Jamaica. Tortoiseshell objects were probably commissioned and given as gifts by English governors and their families to friends in England. In 1682, Lady Lynch, wife of governor Sir Thomas Lynch, sent one set of the combs and case to Lady Arlington, along with ‘400 lbs of the best white sugar from Barbados…and some vanillas’. English sugar merchants in Jamaica signified their financial prosperity and upward mobility through these gifts to relatives and friends in England.

LEVEL 1: Walk back through the British Galleries until you come to the stairs. Once again, follow the U-shape balcony around to the opposite side of the dome into the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries (300-1600). You are looking for Room 63, The Edwin and Susan Davies Gallery.

Manilla

ca. 1600-1800 – unit of currency, brass, Western Europe

Room 63, Medieval & Renaissance, The Edwin and Susan Davies Gallery | MAP

Manillas were a standard currency in West Africa long before Portuguese merchants began trading them from the 1470s. Millions were then made in Europe for export to Africa. Europeans used manillas as currency to enslave African people. Manillas were also traded for pepper, cloth and ivory.

LEVEL 0:

Walk back to the stairs and go down to the big entrance hall with the glass sculpture. From the entrance hall go through towards the Main Shop but take a left in the big hallway just before. You are looking for Room 41.

Tippoo’s Tiger

ca. 1790, Mysuru

Room 41, South Asia | MAP

“Tippoo’s Tiger” was made for Tipu Sultan, ruler of Mysore in South India (1782-1799). The almost life-size wooden semi-automaton consists of a tiger mauling a prostrate figure in European clothes. An organ is concealed inside the tiger’s body, and when a handle at the side is turned, the organ can be played and the man’s arm simultaneously lifts up and down. Intermittent noises are supposed to imitate the wails of the dying man.

Tipu Sultan commissioned this semi-automaton in the 1790s and kept it in the music room of his palace in Srirangapatnam. It was discovered by the invading army of the East India Company in 1799, and seized with all the contents of the palace and its treasury after the Siege of Seringapatam in 1799. The invading army stormed through a breach in the ramparts and, in the ensuing chaos, Tipu and a great many of his soldiers, generals and the citizens of the town were killed.

LEVEL 0: Go back out to the hallway and walk past shop to Room 47F (Buddhism) and go through to Room 45 (Japan).

The Mazarin Chest

ca. 1640, Japan

Room 45, Japan, The Toshiba Gallery | MAP

This extraordinary lacquer chest is one of the most important objects in the V&A’s Japan collection. It was made by highly skilled craftsmen in Kyoto specifically for export to Europe, where ownership of such a luxurious object signified wealth, status and taste. The chest’s name comes from the coat of arms of the French family Mazarin-La Meilleraye, which appears on the chest’s key. In 1800, William Beckford, a British novelist, art collector and slave owner, became the chest’s owner. Today, Beckford is credited with establishing new collecting practices which continue to influence contemporary collectors, yet these were funded by wealth secured through the exploitation of enslaved Africans.

LEVEL 0: Go back through Room 47F (Buddhism) and walk through 47G (Korea) until you come to a left into the Cast Courts. The associations with Empire and Slavery are not as obvious here but it does give you a sense of the British predilection for ‘having’ and ‘taking’. There is also a very funny bit of Victoriana.

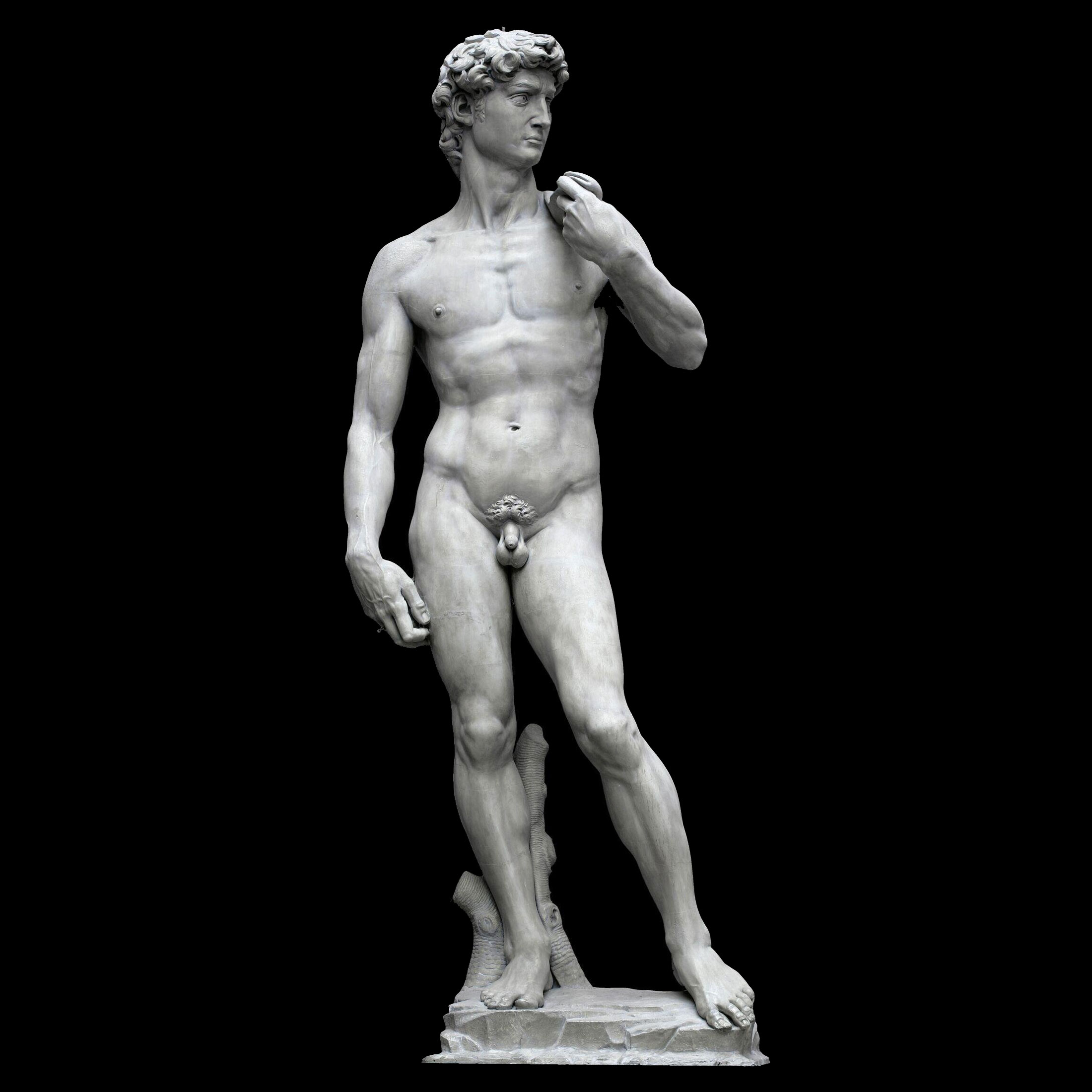

David

1501-1504 (sculpted), ca. 1856 (cast)

Michelangelo (sculptor), Clemente Papi (cast-maker)

Room 46b, Cast Courts, The Weston Cast Court | MAP

For Londoners without the means of traveling abroad, these casts provided a fascinating glimpse into the marvels of European sculpture. One of the earliest major casts of Italian figure sculpture – Michelangelo’s David – sets the tone for the scale and breadth of the objects to be found in the courts. David, which was constructed by the Florentine cast-maker Clemente Papi in the 1850s, is more than five meters tall and was created from hundreds of pieces of a plaster mould taken directly from the original.

Acquired by chance, it was sent to Queen Victoria by Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, supposedly in an attempt to placate the British following his refusal to allow the National Gallery to export from Florence a painting by Domenico Ghirlandaio. The Queen, shocked by the nudity of the cast, requested that a suitably proportioned fig leaf be made (by the London firm D. Brucciani & Co), and hung on the cast using a pair of hooks when dignitaries visited. Today the plaster fig leaf is a popular exhibit on its own.

Let’s Eat!

From the Cast Courts, walk out the other side into Hallway 33 and take a left. Walk through the sculpture until you come to Room 23 – there should be a door going outside onto the enormous John Madejski Garden. There is a great coffee & snacks kiosk in garden in the summer or walk across the courtyard and into the beautiful cafe.

The gorgeous (and historic) cafe was designed by William Morris, Edward Poynter and James Gamble. A young Morris enlisted the help of his friends, Philip Webb and painter Edward Burne-Jones (Poynter’s brother-in-law). Look for meringues the size of your head!

LEVEL 0: Once you are done, find Room 18 (Buddhism) – it runs parallel to the Garden. The next object is not necessarily related to the tour theme but is your mother’s namesake of sorts. 🙂

Tara

ca. 12thc, Bihar, India

Room 18, Buddhism, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Galleries of Buddhist Art | MAP

The goddess Tara (literally ‘saviouress’) was widely worshipped in later Buddhism as an independent deity. In particular, as a divine mother. Here she is represented holding a flowering lotus stem (padma) in one hand, whilst gesturing the granting of wishes with her open hand (varada-mudra). The Green Tara, Syama-tara, is closely identified with Avalokitesvara Padmapani, the Buddhist embodiment of compassion and she is often regarded as his female manifestation.

Tara is set against an elaborate backplate (prabha), which frames her figure and defines her status. She is standing against a throne back, with upright pillars, a cross-beam and a large nimbus framing her head. Behind the throne-back are two stupas that flank her.

LEVEL -1:

From Room 18 (Buddhism), walk through to a large Hallway and turn right into The Blavatnik Hall. Look for the stairs and follow down to Europe 1600-1815, The Sheikha Amna Bint Mohammed Al Thani Gallery and look for your first object in Room 1.

Toussaint Louverture

ca. 1802, Paris

Room 1, Europe 1600-1815 | MAP

For conservation reasons, this object is kept inside a cabinet. If you are interested, please ask a member of staff to open it for you.

The Black struggle against imperialism and colonialism has produced many freedom fighters. Like Nelson Mandela in South Africa years later, Toussaint Louverture was the most significant rebel leader of his time, not just in Haiti, but also across the Caribbean. Born into slavery, the charismatic and articulate Louverture led the Haitian independent movement to victory. This print, depicting him ready for battle, sword held high, served as a call-to-arms for his followers from the 1791 Slave Rebellion, which briefly established Haiti as a Black-governed French Protectorate.

From Room 1, look for Room 2A.

Bust of a Young Man

ca. First half of 18thc, (carved), Venice

Room 2a, Europe 1600-1815 | MAP

This striking life size bust of a young man of African descent is carved in colored marble, black marble for the head and yellow-pink marble for the tunic which is also ornated with Venetian glass buttons. Traces of red paint found on the lips added to the realism of the portrait while the intensity of his gaze is accentuated by inserts of mother of pearl to represent the white of the eyes. The powerful expression of the man conveys confidence and strength.

Although, Africans were often portrayed as servants or sometimes as personifications of the continent of Africa in eighteenth-century Europe, the personal nature of this bust suggests it was a specific portrayal rather than a generic depiction.

From 2A, look for Room 3 – is a long gallery.

Dessert Baskets with Figures of America and Africa

ca. 1765-1775 (made), 1741 (modeled), Meissen (manufacturer), Johann Friedrich Eberlein, (modeler)

Room 3, Europe 1600-1815 | MAP

Europe’s insatiable desire for sugar and other tropical goods buoyed the transatlantic slave trade for centuries. European dessert tables groaned with sugared delights, piled high in decorative porcelain bowls that were often commissioned on demand for the French market. These two dessert bowls are decorated with Black figurines representing Africa and the Americas, amplifying the luxurious and exotic associations with sugar. The households which used such figurines often ’employed’ African people as domestic servants, though they were often unpaid.

Turn the corner in Room 4 and enter Room 5.

Flask

ca. 1600-1700 (made)

Room 5, Europe 1600-1815 | MAP

This carved wooden flask was probably made to hold perfume. Scents, especially those associated with Africa like musk and jasmine, were very popular in the French Court in the 17th century. Even today, for me just the aroma of such fragrances can ignite my senses and create the allure of rich and distant lands, and men with blue-black faces! The flask’s stopper is in the shape of an African male turbaned head. Wealthy owners of such finely carved items like this often employed African boys as high-status domestic servants.

The March

ca. 1718 – 1724, Tapestry

Room 5, Europe 1600-1815 | MAP

This tapestry, made in Brussels in the early 18th century, is a reminder of the integration of African men within the ranks of European armies. Tapestries, like large paintings, were supposedly ‘mirrors of society’, but people of African descent were often lost in the crowd or represented in submissive roles. Yet in the centre of this tapestry, an African man is shown in an active rather than a passive role. For me it confirms the very real fact that African people have a long history of living amongst Europeans in Europe.

Cross into Room 6 (small room).

Parade of the Sons of Shah Jahan on Composite Horses and Elephants

ca. late 17th century (painted), Willem Schellinks (artist), Oil Painting

Room 6, Europe 1600-1815 | MAP

The long-lasting dynasty of Mughal emperors in India is the subject of this imaginary scene. It is thought to depict Shah Jahan (reigned 1628 – 58), one of the most powerful and influential Mughal rulers, who watches his four sons and others parade before him, forming the shapes of a horse, an elephant and a camel. Overhead sit Akbar and Jahangir, the grandfather and father of Jahan, while two East Africans accompany the entourage. Although there is limited research on Africans in India between the 14th and 17th centuries, we know that some became powerful rulers, including Malik Ambar, an Ethiopian military leader who won significant victories against the Mughal empire in the 1600s.

Walk into Room 7.

The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella in the Brussels Ommegang

ca. 1616 (painted), Denys Van Alsloot (painter), Brussels (painted)

Room 7, Europe 1600-1815 | MAP

Look closely to discover three people of African descent within this painting of a grand procession called the ‘Ommegang’, held in Brussels in 1615. The camel driver represents people with darker skin, referred to by Europeans as ‘Moors’. The drummer points to the fact that early musicians of African descent were in Europe at this time, including John Blanke, a trumpeter in the Tudor courts of Henry VII and VIII, and Ferdinand Christian Ali, a drummer in the Austrian court. Lastly, a young African boy with an umbrella of feathers can be seen fanning King Psapho of Libya, highlighting the African presence in traditional European events like this.

Boa Vista

ca. circa 1680, Johannes De Ram (printed and published), Amsterdam

Room 7, Europe 1600-1815 | MAP

The etching depicts a scene on Boa Vista, an island in the Cape Verde archipelago of the west coast of Africa, a historic centre for the slave trade. A white trader has just paid his black assistant, presumably for his help in securing the pile of ivory horns which lie on the ground before them and the shackled Africans emerging from a cave-like prison to the right of the image.

During the 17th century, European audiences were intrigued by representations of newly discovered countries. This etching is from a set of illustrations featuring costume from Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa and the Americas. Here a Dutchman is shown trading ivory tusks and enslaved Africans, with an African man dressed as the artist imagined him. The setting is Boa Vista, an island off the coast of West Africa. By 1650 the Dutch were responsible for enslaving 30,000 West Africans on sugar plantations in Brazil.

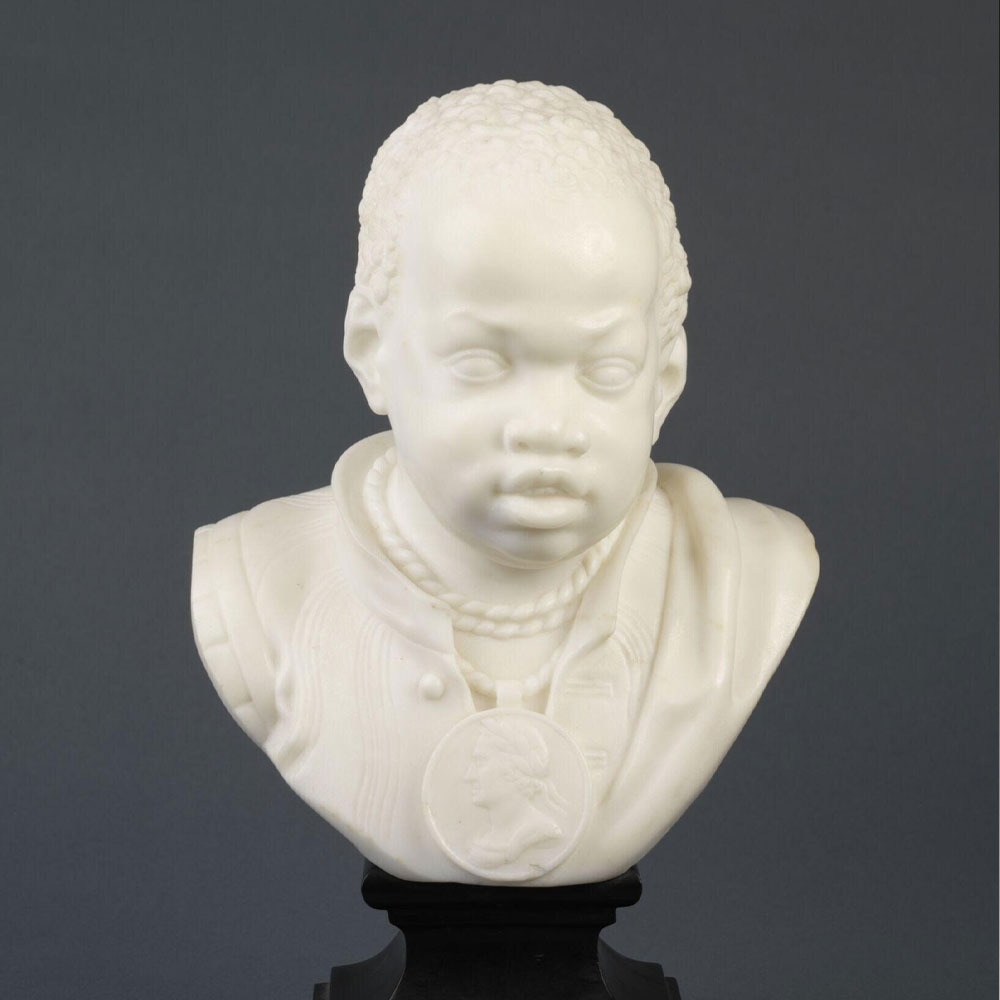

Bust of a Child

ca. 1705-1710 (made), Joannes Claudius De Cock, (sculptor), Netherlands

Room 7, Europe 1600-1815 | MAP

This bust of an African toddler is rather striking, particularly as it is a sympathetic rendering carved in white marble. In the 1700s, it would not have been uncommon to see ships unloading enslaved Africans, alongside spices and fabrics, in the bustling Dutch port of Antwerp, where the sculptor worked. The sculpture is a stark reminder of the loss of innocence and inhumane bondage of the slave trade, and the importance of including all of our voices in retelling collective historical narratives.